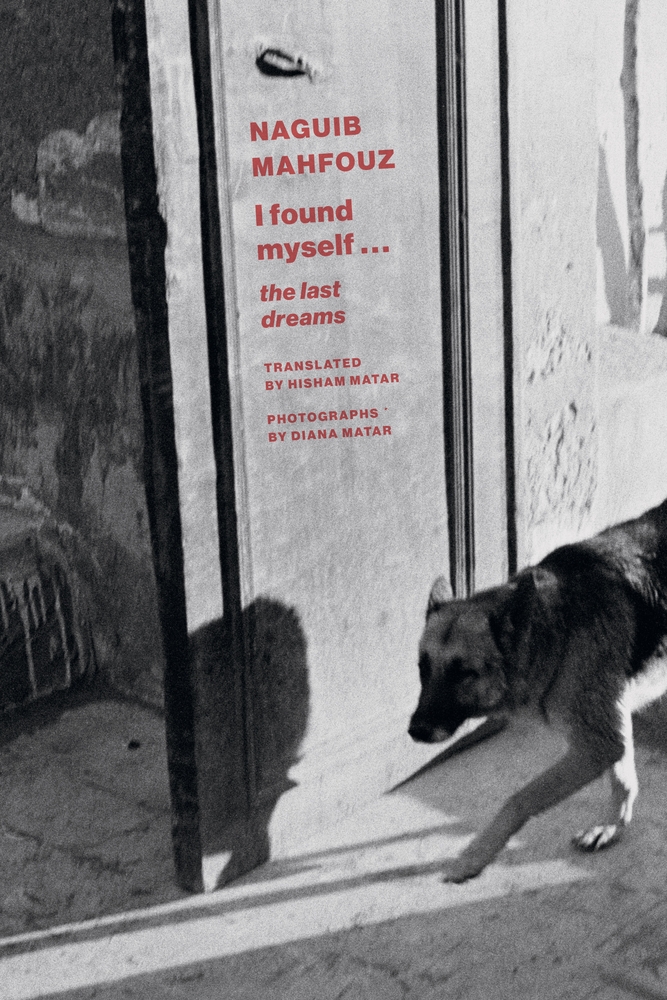

When awarding the acclaimed Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz [1911-2006] the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988, the Swedish Academy noted how “through works rich in nuance—now clear-sightedly realistic, now evocatively ambiguous—[Mahfouz] has formed an Arabian narrative art that applies to all mankind.” The brief, magical vignettes in new posthumous book, I Found Myself: The Last Dreams, translated from the Arabic and introduced by award-winning writer Hisham Matar and accompanied by photographs taken by the celebrated visual artist Diana Matar, are a particular delight, perhaps most so because of the heady a-realism of Mahfouz’s dream world. Hisham Matar’s delicate and sure hand reveals the late Mahfouz’s distinctive voice, and Diana Matar’s evocative photographs add an immeasurable beauty and sense of place, the literal Cairo and the timeless city of the writer’s past, of his slumbrous visions. The last line of the book reads: “And I sensed, after all my pessimism, hope returning.”

I’m as moved by that sentiment as I am with this singular collaboration, this unexpected, memorable journey with this late icon, led by an exceptional translator and photographer, that applies to us, to all mankind.

This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Mandana Chaffa

Hisham, Mahfouz told you once, “You belong to the language you write in.” Like you, I had conflicting thoughts about this statement: I write in English, but my first language, the one I default to, increasingly more as I get older, is the one I was born into, not the one I write in. So too is the nuance between language and country of origin. To solely say that a work was written in Arabic mutes all the shades of where that Arabic originated, and how it might have been altered by external forces. As a writer, a translator, what is your relationship to the languages you write in and speak?

Hisham Matar

A complicated one. To put it simply, English is my principal tool. My relationship to it involves a practice of engaging with its secrets and history, of wielding it to my purpose. And because I was not born into this language in which I write, I am spared the risk of taking such an endeavour for granted, of, for example, pompously assuming a birthright to it, for that would distract me from that elemental truth that all languages are approximations, and that the purpose of every novelist is to capture and set each word into place. And I have several luminary examples of men and women who, like me, arrived into the language from elsewhere. I’m, by turns, fascinated and troubled by their example, by how, for instance, in Joseph Conrad’s English you sense the distances and the ruptures, the loss of innocence, the loss of the ease of taking things for granted. But you are also consoled by the sheer penetrating power of his outsider’s gaze.

Mandana Chaffa

In the foreword, Hisham wrote: “[t]hat same summer we met Naguib Mahfouz, when he was having some of the dreams contained in these pages, Cairo became Diana’s muse.” Diana, would you speak to the provenance of these photographs? There’s such an intimate languor to them, because they are in black and white, because of sharp contrasts and delicate blurriness. So many of them are framed in such a way that they dispense with traditional temporality, they speak of then and now, the future, and yes, the dream state where lines between the real and unreal are more porous.

Diana Matar

From my first visit to Cairo in 1997, I wanted to be in the streets. One cannot escape the constant light of the Nile reflecting off the city’s surfaces—a city where centuries of time are etched into, and at times crumbling away from, those very surfaces. Moments of present, colonial, and ancient time reveal themselves in the most aesthetic ways. If you are sensitive, I think that multifaceted temporality etches itself onto the negative. The safety of the city and people’s kindness in Cairo allowed me, as a woman, to wander the streets day and night without fear. I photographed that way for more than 15 years—never with an agenda—only with desire.

Mandana Chaffa

Diana, your work often explores testimony, memory, and complicated histories and politics, both personal and national. So many of the Cairo photographs in this collection operate in their own temporality: still or in motion; a split-second of the past or perhaps in an eternal present. I can only imagine how many photographs you’ve taken of Cairo across the years; what kind of narrative were you seeking to create for this project, especially knowing Mahfouz?

Diana Matar

When I began choosing which images to include in I Found Myself, there was a magical period of reading and re-reading Hisham’s translations of the dreams. Then came the long, arduous (and exciting) task of delving into my archive to find photographs that might share a similar sensibility with Mahfouz’s short, extraordinary writings. I found the visual narrative by seeking out the overlap in how we each saw the city—surrendering part of my relationship to Cairo in order to glimpse Mahfouz’s. There were many overlaps: images that possessed a dreamlike quality and spoke to the city on multiple levels. Some decisions were more calculated and I made editorial choices I might not have made in another context. For example, Mahfouz often dreams of “B”—an unrequited love. So, I selected photographs of women turned away from the camera or otherwise unrecognizable, as a visual metaphor for that unattainable love. Many of the men in this edit look quite serious, again an echo to the sensibility of the dreams. I love that the edit of images for I Found Myself was shaped years after I took the photographs, and by another artist whose connection to Cairo was deeper and more intimate than my own. It reminds me that making art is both an individual and a collaborative act—and that collaboration doesn’t end because one of the artists is no longer with us.

Mandana Chaffa

Hisham, I love that you initially began these translations for Diana, not for a public readership. It feels more personal to me that this was for a beloved rather than the group, and I feel that sense of hushed intimacy throughout. How did you work together in conceiving this project, and how did it shift as you collaborated? Would you also talk more generally about your creative lives together?

Hisham Matar

Yes, indeed, it did start that way, and an element of this continued throughout the making of the book, which evolved quite naturally, from that simple, first instinct, one Sunday morning in the autumn of 2018, of me reading Mahfouz’s dreams over coffee and wishing so much that I could share them with Diana. I translated a few, and it all evolved from there, eventually turning into a collaboration, because all along I could see Diana’s Cairo photographs beside Mahfouz’s dreams. And therefore, I really think of this book as one by two artists, Naguib Mahfouz and Diana Matar, their evocations, in words and images, of Cairo and of the subconscious; the echoes of a city and the dream world in prose and photographs. As to your other question, about our creative life together, that’s hard to speak about. We are, to state the obvious, husband and wife and therefore share a life, with all that that entails. But we are also two artists who work side by side. We are one another’s first reader, and a conversation, ongoing from the moment we met some three decades ago, about making work, is central to our practice. It is, for me, the most important and intimate exchange.

Diana Matar

Our creative life is so intertwined with life in general it is hard for me to separate the two. It is also very sacred, private and difficult to put into words. An attempt would be to say that our sensibilities allow for the inner privacy and collaboration that is necessary to live and bring work into this world. When Hisham first started translating the dreams, he would read them to me as little gifts. Nuggets of wonder, usually in the morning. Once we got a publisher we worked quite separately and over a few years around doing our other work.

Mandana Chaffa

Would you talk about Cairo? Mahfouz’s Cairo, your own, and perhaps even what I’d call the mythical Cairo, the place that exists beyond geography, beyond history?

Diana Matar

A city, like any landscape, is primarily an intimate place if you have family there. For me Cairo radiates outward from Hisham’s mother’s home—the smell of her cooking, the sounds of laughter and conversation, birds, traffic, and the adhan. And light that changes from soft to exacting as the day passes. Outside the home—the public space—I touch on in my first answer. The magnificence of Mahfouz’s dreams is that he weaves the internal and external with such precision and brevity as if they are one and the same.

Hisham Matar

My family moved to Cairo when I was nine. I lived there until I was fifteen, moved to England to continue my education, and from then on, I’ve been going back to Cairo every year. It’s a city I know well, but where I continue to be a visitor. Those early six years marked me very deeply. I loved its social fluency and vibrancy. When I met Diana my relationship to Cairo deepened through the sharing of it with her. And as a writer, my work is translated to Arabic and published out of Cairo, which brought me into contact with the literary community there, which continues to be touched by, of course, the legacy of Mahfouz.

Mandana Chaffa

I’ve been a vivid dreamer since I was a child, with accumulations of certain themes, though some have shifted the older I get, and especially early morning dreams often feel like a guide, as fanciful as that sounds. Hisham, you wrote “They are, whether we understand them or not, the temperament of our innermost self, the self that, at night or in our imagination, breaks free from the clasp of our conscious will.” Would you both talk about your own dreamwork? How—if at all—has this project impacted you regarding the “creative act” of dreaming—and remembering and sharing them?

Diana Matar

Studying Mahfouz’s dreams didn’t affect my ability to recall my own, but I was inspired by the way he wove his innermost subconscious world into that of society, and real-world politics. As a visual artist, it is something I’m extremely interested in—the consciousness and ability to inhabit a liminal space between the inner self and the social/political era one lives in. And how that can take form within one’s work.

Hisham Matar

I feel similarly. If anything, translating Mahfouz’s dreams made me all the more explicitly interested in dreams and in the trouble involved, given their extreme subjectivity, of sharing them with anyone else.

Mandana Chaffa

Culturally, I’m inclined to look at poetry collections—and there’s something about these pieces that makes me think of poetry—as sources of divination. There’s a great opportunity to flip through these pages with a question in mind and land on one of Mahfouz’s dreams—or equally delightful, one of Diana’s photographs!—as a source of otherworldly insight.

Hisham Matar

That’s such an interesting observation. And for a long time, until today, in fact, I have a chronic slip-of-the-tongue whenever I speak about Mahfouz’s dreams, catching myself saying ‘poems’ instead of ‘dreams’. Perhaps it has to do with the way they negotiate sense and meaning and memory.

Diana Matar

I love this idea, Mandana—as if the dreams and images could each function like a mandala. There are writers who do this for me as well—those I return to for wisdom—where a single phrase suddenly speaks directly to whatever I’m contemplating in that moment. Perhaps it’s a shared sensibility between writer and reader. Or perhaps it’s something more spiritual—something about being open to receiving wisdom, as if the accumulated human understanding of the ages becomes accessible only when we are ready.

Mandana Chaffa

The dreams start at 200 and go to 299. Do these follow on the first volume of dreams that went to about 206? Do these numbers have any other meaning?

Hisham Matar

The first volume, published under the title of Dreams from a Period of Convalescence, runs to about 230 dreams and was published in 2004, a couple of years before the death of Mahfouz. The second volume, published posthumously, runs from Dream 200 (I am not sure why it runs from that number and not 231) and goes to Dream 497. I Found Myself is made up of the first 99 dreams of that second volume.

Mandana Chaffa

Given that Mahfouz was known for his realism, these watercolor-like, flash dreamscapes are exceptionally pleasing to the eye and ear; the open space on the page, the wordless voices in the photographs. And yet, they are grounded by the most human of emotions: love, loss, fear, and always, hope. Impossibly, I see myself in them, or perhaps, the echoes of what we might all share when Hypnos disconnects us from the waking world. How has living with these narratives impacted you, translated into English, translated into photography?

Hisham Matar

That’s what we had hoped for. Diana designed the book, and we agreed early on that we wanted neither the images nor the text to illustrate the other. That, in other words, the photographs and the dreams will not seek to ‘translate’ one another, but are instead involved in what I call a state of resonance, where a third thing occurs. That third thing is what you allude to so beautifully in your question. And yet, the whole thing is shot through with translations, several at the same time: Mahfouz rendering his dreams into succinct narrative pearls; then Diana translating the city; and, finally, carrying Mahfouz’s sentences from the language I was born in, to the one I live in today.

Diana Matar

I think your use of the word ‘translation’ here is a fascinating thing. There is translation of metropolis, of temporality, of desire, of words and turns of phrase, of silver and light onto film and paper and then again into digital form, and to the printed page. Each step alters the original, yet allows a way in— to consider Mahfouz’s city and his consciousness. So, the very idea of translation becomes an invitation for the reader/viewer/translator/photographer to have a relationship with place that might interreact and echo another’s gaze.

I Found Myself: The Last Dreams

By Naguib Mahfouz

Translated and Introduction by Hisham Matar

Photography by Diana Matar

New Directions

July 22, 2025

Mandana Chaffa is a writer, editor and critic whose work has appeared in a variety of publications and venues. She is founder and editor of Nowruz Journal and an editor-at-large at Chicago Review of Books. She serves on the boards of Brooklyn Poets, where she is Treasurer; the National Book Critics Circle where she is vice president of the Barrios Book in Translation Prize and co-vice president of Membership; and is also the president of the board of The Flow Chart Foundation. Born in Tehran, Iran, she lives in New York.

Wonderful post 🎸thanks for sharing🎸