The first essay in Jonathan Gleason’s Field Guide to Falling Ill tells the story of his second cousins, two of his mother’s cousin’s children who died in early childhood of Tay-Sachs disease. Dr. Bernard Sachs, the neurologist who first noticed the symptoms of the disease in children in late-nineteenth-century New York, did not know how to treat it. “The families of the children he treated had come to him for help, for a cure, for relief,” Gleason writes. But “all he could do was describe, helplessly, what he observed.”

Gleason begins his essay collection, the inaugural winner of the Yale Nonfiction Book Prize, with this implication that observation is “helpless.” But we know that medical discovery is often rooted in observation, and the book, with its steady and careful accumulation of details, makes the case that observation can amount to meaning.

One of the strengths of Gleason’s collection is that he consistently chooses the less tidy version of every story. There’s the patient he interprets for who complains of textbook heart attack symptoms yet displays no outward signs of a heart attack, a man unable to “make [the doctor] feel what he knows deeper than words: that something is wrong.” Or the essay “Blood in the Water,” written in the form of letters to Gaëtan Dugas, the man who has become known as AIDS Patient Zero but was not, in fact, the epidemic’s first patient. Or Gleason’s personal stories: of being on a bus when a man walked on with a gun—a gun which turned out to be an airsoft toy, and where the only person injured was shot by police—or of surgery and persistent treatment to address a blood clot that stubbornly remains. The medical narratives amplified in popular culture are often straightforward or triumphal, with a mysterious illness identified and healed or a diagnosis overcome; Gleason instead lingers in the moments of uncertainty and difficulty. “I can tell you what it’s like to be in the postscript of illness,” he writes, “its undead state, where the crisis has passed but recovery isn’t certain. It’s a dull, heavy place.” He never omits the small facts that make a narrative less linear or smooth.

Gleason’s essays suggest that medicine should resist the pressure for efficiency precisely because healthcare isn’t linear. His own blood clots require appointment after appointment as the initial surgery doesn’t have the expected result. Even death, as Gleason points out, is “profoundly technical,” a series of stops and starts “recorded precisely in minutes and seconds, though this record is a lie of medical and legal utility.” Gleason attributes the case of Dr. Husel, a doctor accused of prescribing overly large quantities of painkillers to terminally ill patients, to “the realities of his profession.” Gleason suspects “that he ended these patients’ lives because it was the quickest path, an efficient solution to the troublesome problem of excess life.” Where other works of narrative medicine argue that empathy is the solution, Gleason contends that empathy is a Band-Aid over “material failures … that what limits our humanity in the first place are these material concerns.” Empathy won’t magically improve healthcare if those material needs remain unaddressed and efficiency remains the highest priority.

Many of the essays in Field Guide to Falling Ill are written in a braided format, and I found the strongest to be those where the connections between the braided ideas were clearest or the structure was most straightforward: “Field Guide to Falling Ill,” which pairs Gleason’s experiences as a medical interpreter and as a patient, and the final essay, “No Harm,” about Dr. Husel’s trial. But even when the connections feel less direct, the braided approach demonstrates how deeply health inequities are woven into our lives, well beyond the walls of the hospital or doctor’s office. Health isn’t just a matter of doctors’ care and patients’ access to medication—aspects of healthcare that are already much more complicated than they should be—but is also a result of the design of spaces like prisons and of neighborhood change and gentrification.

Even healthcare isn’t just about healthcare. In “Field Guide to Falling Ill,” Gleason shares a patient-doctor moment he interpreted in which the doctor seems to give up on connecting with the patient. After she tells a whirlwind emotional story about her father’s experiences with pancreatic cancer, misdiagnosis, and hospitals, the doctor can offer her only prescriptions for blood pressure medication and anti-depressants. “The problem has slipped the bonds of medicine,” Gleason writes. But as his essays make beautifully clear, most medical problems do.

NONFICTION

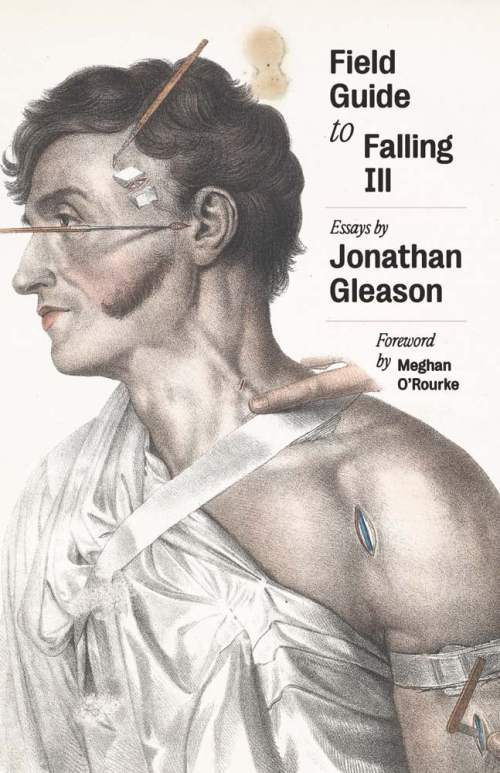

Field Guide to Falling Ill

By Jonathan Gleason

Yale University Press

Published January 27, 2026

Sara Polsky is a writer, editor, and educator in New York City. She is the author of the YA novel This Is How I Find Her.