Shared trauma often brings people closer together with the common experience building a unique bond. But those shared memories can also create distance between two people who were otherwise close. For the sisters in Nina McConigley’s debut novel, How To Commit a Postcolonial Murder, their intimacy ebbs and flows as the strain of trauma both brings them together and wedges them apart.

Georgie and her sister Agatha Krishna live in Wyoming. Their father works the oil fields, and their lives are tied to the fluctuating value of the resource. “We weren’t poor. We weren’t rich. We were dependent on the price of oil,” Georgie tells us.

Their mother has not seen her family in India for fourteen years until the arrival of her brother, his wife, and his son. Their arrival changes everything. Intended as a temporary stay, Vinny Uncle and his family take over a room in the house, and suddenly Georgie and Agatha Krishna are forced to share a room. Not only do they lose the luxury of privacy, the source of their forthcoming trauma is invited into their home.

Vinny Uncle doesn’t work, and his contribution is watching after the girls at home, but mainly smokes cigarettes and watches television. And then one day he assaults them.

The novel is narrated by Georgie, who reflects back on events that transpired over the course of a little more than a year in the mid 1980s, beginning with the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger. The narrative draws on these types of historic markers; its references to Reagan and the Cold War and the re-release of The Song of the South create anchor points grounding the story in time and place. But these details also highlight how long the trauma has lingered for Georgie.

Throughout the novel, Georgie addresses the reader directly, in a conversational way. When she finally explains why they decide to murder Vinny Uncle, she says: “Why would you kill your own special uncle? All right, I’ll finally tell you.” This relaxed tone adds to the sense that time and space have passed since the events unfolded. Also interspersed through the book are various quizzes, the sort that are published in magazines targeting teen girls about whether boys like them or how to determine if they are ready for sex. It’s a reminder that Georgie and Agatha are children. And although these narrative disruptions relax our relationship to Georgie and help build our trust in her as a narrator, she also tells us straight up she will murder Vinny Uncle later in the story. Even as the story meanders through the ordinary comings and goings of her life, she reminds us of what’s coming. At first, we as readers wonder if she’s serious. We’re also left wondering why and how, and whether she is justified. All of this builds suspense into the narrative.

Georgie explains how she disassociates, and in some ways it feels as though her telling of the novel is in a way its own kind of dissociation. The girls devise a way of killing Vinny Uncle in a way that is undetectable but also unreliable. The story is told through brief vignettes that feel disconnected and often without plot; we witness school plays, the death of their cat after eating antifreeze, the arrival of first menstruation, visits to the mall, hiking with the girl scouts. Individually these short briefs amalgamate childhood and sisterhood and build out real-feeling characters. But they are less useful for building a novel; what ties them together is the omnipresent promise of a murder.

Vinny Uncle eventually succumbs to death. While there is some relief, his passing also unravels the intimacy Georgia and Agatha Krishna shared. Once bonded by the trauma induced by Vinny Uncle, his passing weakens that link.

There are of course other elements to this novel beyond the explorations of the limits of sisterhood. The family are outsiders in Wyoming, and racial tension bubbles under the surface. Georgie’s father is white, their cousin Narayan is much darker, and the issue arises in school. And they may not be poor or rich, but they are certainly closer to poor, especially as the price of oil continues to deflate, which underscores the family’s precarity over the course of the novel.

The primary focus of the novel remains the relationship between the sisters, and how they navigate the trauma of their childhood. And in this space, the book succeeds at capturing complex emotions. How to Commit a Postcolonial Murder will resonate strongly with a specific type of reader who wants to explore the intimacies of sisterhood, particularly through the lens of otherness. McConigley has captured a unique narrative experience and shared it with an equally unique voice.

FICTION

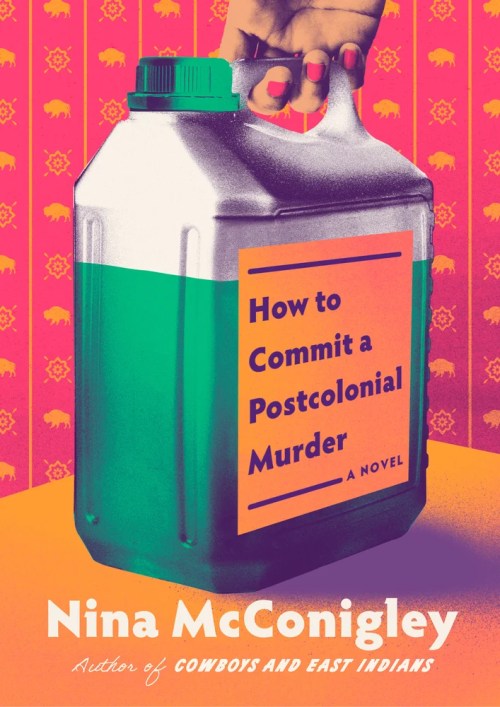

How to Commit a Postcolonial Murder

By Nina McConigley

Pantheon

Published January 20, 2026

Ian MacAllen is the author of Red Sauce: How Italian Food Became American, forthcoming from Rowman & Littlefield in 2022. His writing has appeared in Chicago Review of Books, The Rumpus, The Offing, Electric Literature, Vol 1. Brooklyn, and elsewhere. He serves as the Deputy Editor of The Rumpus, holds an MA in English from Rutgers University, tweets @IanMacAllen and is online at IanMacAllen.com.