Movies about Hollywood often win awards; the industry loves to watch itself on the screen. Books about writing books are the same, for the same reason, and so campus novels thrive on this self-infatuation. But the Hollywood novel, a genre almost as old as the film industry, is something else, so often written by literary authors looking into the industry from outside it, like, for instance, Fitzgerald’s final, posthumously published novel, The Last Tycoon. The allure of the exotic draws novelists to the genre.

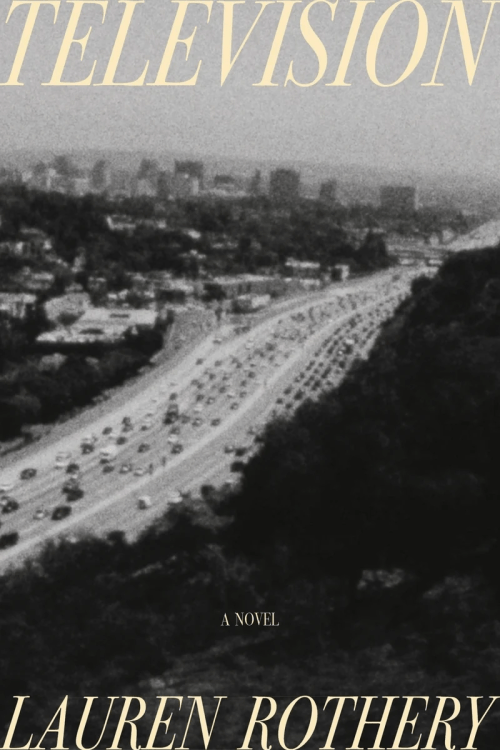

In Lauren Rothery’s debut novel, Television, Hollywood is less foreign. A director and screenwriter, Rothery’s enchantment with Hollywood is perhaps less a curiosity, and more an observation. Rothery is not a celebrity. There are no Marvel film credits, but she has worked as a director and screenwriter.

Television alternates perspectives, shifting from Verity, a famous, wealthy actor, and Helen, his longtime friend and occasional lover. Each tells us their version of events unfolding as Verity unravels his life. He drinks too much, and invents a lottery to give away all the earnings on his latest film, which drives ticket sales and makes him even more in demand.

Halfway through the book, we’re introduced to Phoebe, a screenwriter who happens to be writing a screenplay about friendship. She is in France, clearing out her dead grandparents’ house, dreaming up a film script. It’s an Inception, a story within a story, or perhaps an Adaptation, an intentional misinterpretation of the story unfolding before us. Her narrative is the weakest of the three, although she does make an interesting observation about money. She’s convinced that, with $500,000 in the bank, within ten or fifteen years, she could have a life of independence, provided she saved for that entire period of time and lived with smart financial decisions. Phoebe is setting up a broader criticism about wealth and power in Hollywood, but the message is muddled.

These three perspectives are interwoven together, beginning with Verity coming undone while flying back to Los Angeles. After drinking too much on the plane, he begins to unsettle everyone by trying to talk to the pilot. His celebrity ultimately protects him from serious consequences. These early chapters are succinct and the prose sharp, a pleasure to read, even as we’re served up a bit of backstory. What drives the reader’s interest here is the complicated relationship between a famous person and a not-famous person. There are other subtexts, including a comparison of success and failure, and the suggestion that not achieving fame is akin to failure itself. The heart of this book attempts to assess fatalism, whether it’s chance that determines our outcomes, or inherent skills.

Helen and Verity became friends and lovers before he was famous, and somehow against all odds, their friendship remains intact. The problems in this relationship begin to reveal themselves, particularly around the power dynamic between the two of them, which develops when Verity buys up the apartment complex Helen lives in. He’s not intending to manipulate her, only keep her apartment affordable. And that’s where Television begins to drag. There’s plenty of setup for a tough critique of money and power, but so much of this narrative is delivered in a way to render that biting cut softer. Verity is a rich guy who lives life easily. He’s affable and entertaining, and as readers, we’re meant to sympathize with him through his kindness towards Helen and the discomfort he feels about his wealth and success. But even when he’s doing unlikable things or breaking societal conventions, his presence on the page remains alluring. Is this charisma his good luck or some innate skill? That conflict is presented as the central question of the novel, but no clear resolution materializes.

Luck and chance weave throughout this narrative. Good things keep happening to Verity, despite his bad decisions. In discussing how they first met, reflecting back, Verity tells Helen he came over to talk to her because of the way she looked. Eventually she posits, “Is it at all who you are? Does it become you? Or is it really only chance?” Verity has an answer easily: “It’s chance.” Rothery clearly wants us to see success as tied to good luck, while also telling us Verity is a skilled actor. Rothery wants it both ways—Verity is deserving of his fame because he’s a skilled actor, but also he was handsome, and even if he hadn’t been skilled at acting, he was pretty enough to succeed. Luck and merit, without choosing sides.

The modern screenwriting theory known as the Save the Cat principle conceptualizes film structure with specific beats for plot-driven storytelling. The idea has been criticized for undermining creativity in Hollywood films. Television has the opposite problem. There’s no cat to save. The needs and wants of these characters never materialize, and what is hinted at shifts and sways through the story. But neither Verity nor Helen are ever really moving forward. Traditional plot gives way to vibes.

However, that isn’t to say Helen and Verity aren’t thoroughly intriguing. As Verity crashes out, we want to pay attention for the same reason we watch any disaster. We know it’s happening but watching the disaster unfold is the entertainment. The success of Television is in crafting characters who hold our interest even through a relatively plotless story.

If there is a premise, a desire, it’s Verity’s listless lottery. He endeavors to give up the money he has accumulated from acting. In the first iteration, he convinces moviegoers to buy theater tickets on the promise that each ticket is a chance to win his entire salary for the film, including points on the back end—a percentage of the box office. This off-the-cuff game turns into his main life objective. The movie is a success, Verity earns nothing from it, and when the studio is ready for a sequel, he agrees to give away his money in another lottery. Verity’s first lottery sets off the other studios to host their own ticketed lotteries. We’re given a glimpse of an alternative future where attending a movie includes entering a lottery potentially worth millions, but this plot is never explored deeply. Instead, the focus shifts to Verity giving away his fortunes, and his properties, of which he owns many. Verity giving away his money is an attempt to balance his good luck without truly addressing the question of equity.Television is as much an ode to Hollywood as it is a critique. There is in some ways a celebration of how these characters live their lives, whether it’s writing screenplays in France or laying about drinking all day. Hollywood unlocks those perks. But whether the novel addresses how luck molds outcomes, there isn’t necessarily a resolution—there’s no happy Hollywood ending.

FICTION

Television

By Lauren Rothery

Ecco

Published December 2, 2025

Ian MacAllen is the author of Red Sauce: How Italian Food Became American, forthcoming from Rowman & Littlefield in 2022. His writing has appeared in Chicago Review of Books, The Rumpus, The Offing, Electric Literature, Vol 1. Brooklyn, and elsewhere. He serves as the Deputy Editor of The Rumpus, holds an MA in English from Rutgers University, tweets @IanMacAllen and is online at IanMacAllen.com.