On November 2nd, 1975, world-renowned filmmaker and poet Pier Paolo Pasolini was found murdered in Ostia, Italy. His body had been subjected to disfiguring violence—not just beaten but run over repeatedly with his own car and partially burned—and many suspected a Mafia-style revenge killing. Beloved and detested in equal measure for his uncompromisingly Marxist politics and the taboo subject matter he tackled, including homosexual desire, he’d recently completed work on Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom; its extreme content would become an endurance test for cinephiles. Though 17-year-old Pino Pelosi was convicted of the crime in 1976, he eventually recanted and there’s long been speculation that Pasolini’s death was linked to rolls of film from Salò that were rumored to be stolen.

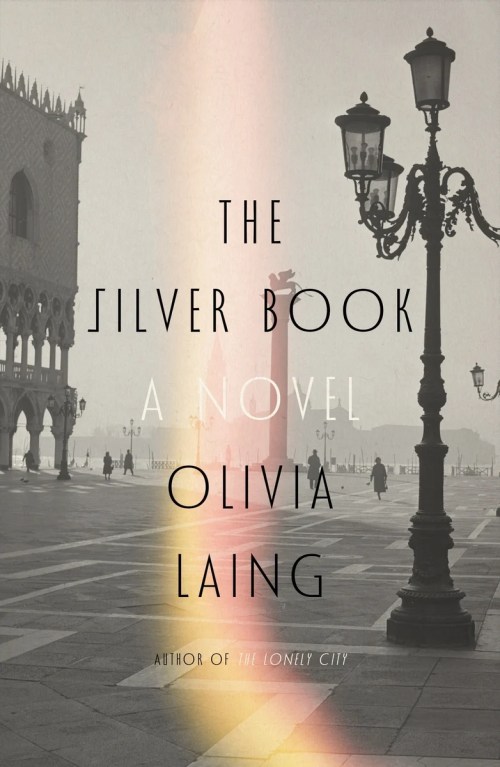

Given the public’s insatiable appetite for true crime, it’s a bit surprising that some enterprising podcast or documentary crew hasn’t made an attempt to dig into the juicy details of such a notorious unsolved mystery—involving a famous figure, no less. But Olivia Laing’s new novel The Silver Book takes a sideways approach to the tragedy. True to their cultural critic background, Laing is much more interested in capturing the coolly hedonistic, intellectually adventurous lifestyle that Pasolini embodied than telling a straightforward story about the director himself. His part in the plot is tertiary but he casts a long shadow.

The book starts in motion, as is only appropriate for a work set in the world of movie making. A young queer man we’ll later learn is named Nicholas must take flight from London following an unspecified incident that’s made the papers. An art student with a rudimentary knowledge of Italian, he decides to head for Venice, a place he’s only seen onscreen. In films like Death in Venice and Don’t Look Now, it’s a sinister city of mortal decay and moral relativity, a dark and twisted place for dark and twisted deeds. It’s September 17th, 1974. Though Nicholas won’t cross paths with him for several weeks yet, a countdown clock to Pasolini’s death has begun.

Once in Venice, Nicholas immediately attracts the attention of an older gay man named Danilo, who’s in the city on a research trip for a Fellini film about Casanova, sketching buildings and rooms that will later be recreated on set. Savvy readers, or those motivated to do some Google sleuthing, will identify him as Danilo Donati, who was an Oscar-winning art director and costume designer. That night they share a bed. By morning, they share a career, with Danilo enlisting Nicholas as his apprentice. Soon he’s spiriting him off to Rome to work alongside him at the famed Cinecittà studio.

Nicholas’s initiation into the dream factory is rocky, but it will be catnip to film connoisseurs. Scenes of location scouting and costume fitting might risk alienating readers without a deep bench of movie knowledge, but Laing’s evident enthusiasm for the material is infectious. This is a world of aesthetes and The Silver Book has an aesthetic beauty to match. When we meet Fellini, embroiled in his latest fiasco— which was constantly over budget and delayed multiple times before its release in 1976—he’s rendered as a man of orgiastic sensibility. “[H]e just has to make everyone love him,” as Danilo puts it to Nicholas, but the designer is no less exacting of a taskmaster. His clothes are “a portal” and their demanding contours have enraged such divas as Elizabeth Taylor and Maria Callas. There’s an ironic brutality to Danilo’s adherence to sensuality that will serve him well when Fellini’s film is put on hold and he and Nicholas decamp for Pasolini’s set in Mantua for what will become the director’s final project.

Salò was a real place. It’s where Mussolini and his Nazi thugs were ferried by the Germans in 1943 after he was deposed from power. “A new republic of unparalleled viciousness and cruelty,” as the character of Pasolini describes it to Nicholas and Danilo. “Salò is a location on a map, a moment in time, a state of mind, coming and going, perhaps even now approaching in the rear-view mirror.” These are words that Laing deposits in Pasolini’s mouth, but they’re no less true for being a fictional invention by an author. For as long as fascism has existed, it’s been imperative for artists to attempt to interpret its poisonous ideology, in part because many have an intimate understanding of it both as victims and perpetrators. Filmmakers, Danilo points out, can be tyrants, too. Unfortunately for Pasolini, his attempt might have killed him.

It’s the potential political motivations behind his murder that make The Silver Book’s publication now feel so urgent. There’s a noirish thrill to the twists and reveals of its second half, as Nicholas’s past comes to light and he gets unwittingly roped into the scheme against Pasolini. And there’s a palpable lushness to Laing’s use of language that mirrors the carnal pursuits of their characters. These entertaining qualities don’t negate the seriousness of their ultimate purpose of interrogating the darker aspects of human nature at a time when doing so could be considered dangerous. The same was true of Pasolini’s work; it could be vicious but was also ribald and joyful. It’s also worth reconsidering in light of the current climate, when voices that speak truth to power are being increasingly silenced, or are terrified of speaking at all. “[E]very construction must necessarily contain a region that remains unseen,” Laing writes early on. If that’s the case then, as this potent novel demonstrates, whether in art or politics we must be careful who’s doing the constructing.

FICTION

The Silver Book

By Olivia Laing

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published November 11, 2025

Sara Batkie is the author of the story collection Better Times, which won the 2017 Prairie Schooner Prize and is now available from University of Nebraska Press. Her stories have been published in various journals, honored with a 2017 Pushcart Prize, and twice received Notable Story citations in the Best American Short Stories anthology series. She also writes a monthly Substack called The Pink Stuff. Born in Bellevue, Washington and raised mostly in Iowa, Sara currently lives and works in Madison, Wisconsin.