Samanta Schweblin is the master of dread. Her stories are part of the growing literary movement that mixes psychological and social realism with touches of horror and suspense; releases such as 2014’s Fever Dream have enchanted and haunted readers. This new collection, Good and Evil and Other Stories, translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell, will pull in readers and leave them, shivering, in the dark.

Schweblin’s newest collection is unsettling, unnerving. A woman attempts to die by suicide, only to survive, forced to go through the rest of her day as if everything is normal. An old friend tries to explain to Elena what happened the night Elena’s child died, and extends a truth, a hope, that could be as revelatory as it could be damaging. A cat haunts a woman who swears that she won’t survive its death. Two sisters use their summer vacation to try and give an alcoholic poet new “Inspiration” and bring her back to life.

The stories are as uncanny as they are familiar. The death that haunts these stories is not fantastical. Sudden deaths are one of the horrors of our daily existence on earth. Schweblin asks us whether the shock is what hurts the most. Whether slow, expected death, the kind that comes with dread, is better than sudden. Whether survival, the need to continue on day by day after being part of a sudden death, being haunted by it, is the worst of all.

In the masterful “An Eye in the Throat,” a young boy swallows a battery under his father’s watch, and a rush of guilt and resentment follows. When the permanently mute young boy is accidentally left behind at a gas station not long after his final surgery, his parents are left permanently scarred by the fear and blame that rushed through them in the minutes of panic between realizing he was gone and finding him again. Both are sure something happened to their boy, changed him, in those minutes, but they don’t know what it is. What they do know is that they are changed by it, in ways that are irrevocable.

Schweblin does reveal what happened to the boy, what it is that changed him, with masterful care, letting the revelation bloom in the reader’s chest, letting them discover it as the father does, sharp and smoky and choking. Schweblin is the master of dread, but this story proves that the only thing worse than all-consuming anxiety and never-ending questions is discovery, the kind of finality that one could drown in.

In “William in the Window,” the woman’s cat does die. But the worst moment is when she realizes that the cat is not, in fact, haunting her. He is simply gone. In “A Fabulous Animal,” our protagonist isn’t sure whether reopening a wound, giving hope to a brutal story, would be better or worse for the mother of the dead child. In “A Visit from the Chief,” the most lasting hurt is from the lack of a bullet hole, a bullet the protagonist swears she heard but can find no evidence of. The damage, the grief, the trauma, seem to leave no mark.

In “An Eye in the Throat,” the boy at one point wonders, if he pushed a finger through the permanent hole in his throat, whether that hurt would touch his mother or father more. “There is a hole in my throat, a hole in my body that hurts in theirs,” he thinks, and tries to decide who he would find there, if he reached in, if he probed—imagining the hole as an eye, as something that could see, that could reveal. That’s precisely Schweblin’s genius: the worst hurts in her tales are not physical, and do not bleed. Her horrors come from moments of seeing pain in another we were meant to protect, from moments of silence, the moments before the truth becomes solid and impossible to escape, the moments when we discover what we would really do if faced with the worst thing. The worst hurts are the ones that stay with us, aching, hard to face, the holes within ourselves.

This is what has made Schweblin the icon of a rising genre, a master of the unsettling short tale. She unsettles readers, leaves them uncertain, leaves her protagonists still trembling. Inhabiting one moment of their lives forever, repeating it constantly, turning it over in their hands. Schweblin evokes our own darkest fears and deepest hurts. She reaches into a hole in her throat and touches something deep within all of us, a probing hurt that aches in all of our chests the same. She evokes dread, grief, death, fear, illuminates them, and leaves the reader to mediate within them—to turn her questions over in their hands, and see how they illuminate our own inner shadows.

FICTION

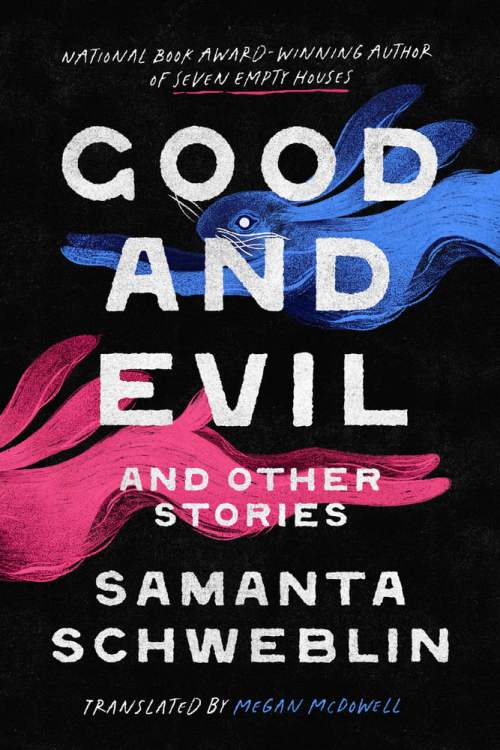

Good and Evil and Other Stories

By Samanta Schweblin

Knopf

Published September 16, 2025

Leah Rachel von Essen is a freelance editor and book reviewer who lives on the South Side of Chicago with her cat, Ms Nellie Bly. A senior contributor at Book Riot, and a reviewer for Booklist and Chicago Review of Books, Leah focuses her writings on books in translation, fantasy, genre-bending fiction, chronic illness, and fatphobia, among other topics. Her blog, While Reading and Walking, was founded in 2015, and boasts more than 15,000 dedicated followers across platforms. Learn more about Leah at leahrachelvonessen.com or visit her blog at whilereadingandwalking.com.