As I read Kate Broad’s debut novel, Greenwich, the coming-of-age story of Rachel Fiske, who spends the summer before her 18th year at her wealthy aunt and uncle’s house in Greenwich, Connecticut, I kept thinking, Rachel’s not going to say that. She can’t say that. Oh! She said it! In short, Rachel is a character who says the quiet parts out loud, and in so doing, forces readers to confront the things they’d rather not discuss or just pretend weren’t happening. Rachel doesn’t let anyone off easy. Including herself.

I recently spoke with Kate about what makes Rachel so unnerving. During our conversation, we talked about how race and wealth play themselves out in the novel, what motivates her main character’s “good” intentions, how she went about writing a novel that raises questions instead of answering them, and why that was important. We also talked craft, specifically about genre blending and how she used a reminiscent narrator to move the story along and increase tension.

The interview has been edited for length.

Sara Maurer

You begin Greenwich with an epigraph from Hannah Arendt’s work, The Human Condition, that says, “One deed, and sometimes one word, suffices to change every constellation.” How does this line prepare the reader to enter the world of the novel?

Kate Broad

The summer Rachel goes to Greenwich, an accident happens that changes the shape of her life and forces her to make a decision she’s still wrestling with years later. The accident is in some ways random, the way that accidents are—but it’s not like it comes out of nowhere. It’s the result of all the words and deeds that came before it. Even our smallest choices can have a profound impact, which I think is what Arendt is getting at here and what I wanted to explore in the novel. The way we speak to others, how we treat them, how we conceive of ourselves, all set the stage for how we move through the world, and that has consequences.

Sara Maurer

Reading Greenwich made me wonder how the lies we tell ourselves about a population or group, such as immigrants in Ohio eating their neighbors’ pets, give us permission to mistreat them. How does Greenwich confront these narratives?

Kate Broad

Narrative can be weaponized to make people believe all sorts of things, and even when confronted with the truth, people will still insist on the story they like over the facts right in front of them. The first step to challenge a false narrative is, I think, to recognize that it’s even happening, especially when it might be subtle—like an assumption about who is going to work in a corner office, to use an example from Greenwich, versus who is going to be emptying that office’s trash. Rachel brushes off these assumptions of hers as silly mistakes, but they aren’t. Again, it’s the seemingly small, everyday steps that lead to the accident and the rupture in Rachel’s relationships. People only believe huge, dehumanizing lies once they’ve normalized seemingly small falsehoods to begin with.

Sara Maurer

One of my favorite passages from the book is this:

“It’s hard to remember now what it felt like, not just being young but young in that world at that time. Always, always, the careful distance you agreed to keep. Even face to face, nose to nose, two separate bodies lying in the dark.”

Greenwich is, above all else, a coming-of-age story. How are you hoping the reader’s self-awareness expands alongside Rachel’s?

Kate Broad

I’m so glad that quote resonated! I really wanted to capture the push-pull of wanting something you know you can’t have, or feeling what you aren’t “supposed” to feel when you can’t just turn that part of you off. It’s a coming-of-age-at-any-age book, because even in adulthood, Rachel’s still trying to work out how to live a full and honest life. So many of the problems in the novel stem from not just a lack of self-awareness but from believing that there’s one way to live and we all have to adhere to it. The man makes the money, the woman does the unpaid labor to enable that money-making, everyone has to keep up appearances or else. I’ve had readers tell me that reading Greenwich made them look more closely and critically at themselves, and I think it takes a lot of honesty to admit that. The fact is that none of us are immune to the social, political, and economic forces that go into creating and maintaining our world.

Sara Maurer

Rachel is not a particularly likable character. There’s something unnerving about her interiority. Why do you think she has that effect on readers (at least on this reader!), and why did you choose to lean into that discomfort?

Kate Broad

I definitely gravitate toward reading books with characters who are human, which means flawed, which often means “unlikeable” although that’s a term that so often gets applied to women, it feels so loaded and gendered. I love books that explore multiple points of view, but there’s a bit of a narrative sleight of hand that happens, because you can give the reader insights they only know because they get to hop into another vantage point. In real life, we can never get out of our own heads. The challenge in writing was to stick to Rachel’s limited perspective while making clear that it is a limited perspective; there’s a whole world beyond the confines of her point of view. In my first draft, I started writing from the third person because I thought I needed that distance to show that the novel is critical of her choices. But the book came alive so much more when I changed it to first person. I had to get closer to Rachel before I could really see what the novel could do.

Sara Maurer

Would Rachel characterize herself as a “good” person? Would Claudia? Would the Corbins? Do you think their responses would change as the story unfolds?

Kate Broad

The first line of the book is: I went to Greenwich at the last minute, to do what I thought would be some good. But of course “good” can have competing definitions, because what serves one person might come at another’s expense. In a way, this obsession with being good—with being seen to be good—is what drives Rachel so far off track, because she’s more worried about what others will think of her than what she actually believes. People don’t see themselves as villains. Rachel’s aunt and uncle, the Corbins, would absolutely see themselves as good people, just as Rachel has countless justifications for how snooping in her aunt’s things isn’t that bad, for example, or how she’s doing the “right” thing in helping her family no matter the costs. I do think by the end of the novel Rachel has a different perspective on her own goodness, but I suspect that’s something readers will debate. Claudia is arguably the only character who develops the self-awareness to recognize and move past whatever mistakes she may have made.

Sara Maurer

On a writerly level, how did the use of a reminiscent narrator advance the story and heighten tension? Were there times during the drafting process when you had to pull back on this voice or deliberately insert it?

Kate Broad

Another thing Arendt talks about in The Human Condition is how we can’t know what a story is until we get to the end of it. Rachel knows what happened that summer, and so bringing in her adult perspective allowed me to add juicier foreshadowing, plus a fuller exploration of the ramifications of these events on the rest of her life. I was able to incorporate another layer beyond what a seventeen year old would think and know. Like in the line we talked about, where Rachel is trying to remember what it felt like to be closeted and uncertain in the ’90s: we get how she felt then, how she feels now, and the ways that remembering something changes our memories through the very process of revisiting and reinterpretation. The key was to be deliberate about when to let her adult voice come through and when to pull back. The story had to unfold organically, without imposing an adult’s voice onto a teenager’s experiences.

Sara Maurer

The writing throughout the book is stunning. Here’s another favorite line:

“The air had a brittle quality, as though I’d walked into a room where an argument still clung.”

I could list 100 other examples. What has your writing journey been, and how did drafting and revising Greenwich develop your craft?

Kate Broad

Thank you so much for saying this. The writing itself is always the most important thing for me. Figuring out how to tell a story is tough, though—I had to teach myself how to make something happen on the page. I learned this by reading—often by literally outlining the structures of other novels I admired—and by practicing different narrative styles. I have ten romance novels published under a pen name, which may come as a surprise, but if you want to figure out how narrative works, genre fiction is a great way to do it. I also have a PhD in English and used to work as a freelance textbook writer, so I got a lot of practice writing for different audiences, writing on a deadline, and incorporating feedback. Now looking back (with my own reminiscent narrative voice!) I can see how it all laid the groundwork for Greenwich. I had to write a million other words before I could arrive at this story.

Sara Maurer

You’ve mentioned that Greenwich blurs the line between literary fiction and thriller. Thrillerary?? Ha ha. Which elements of these genres did you adhere to? Which did you stray from, and were these moves intentional or intuitive?

Kate Broad

I actually think it’s sort of a literary domestic suspense. Lit-spense? The lines definitely start to blur. I write what I like to read, and what I’m always looking for more of is story. Greenwich is, in many ways, structured like a romance novel, with a central relationship that builds, comes together, and then experiences a crisis. But it’s clearly not a romance novel—it just has some similar beats (which many novels adhere to). I used conventions of suspense to build tension around the question of what happens and how the tragedy will unravel this family’s life, but the writing itself, and my deep love of ambiguity, also came from lit fic (because what in life is ever clear-cut). A lot of this felt intuitive. It’s also studied, though. I read widely and learn so much about how to build character and layer a story by seeing how other authors do it.

Sara Maurer

At the end of the book, the reader has the sense that the story could have played out differently, should have played out differently. But where? How? You resist the urge to provide prescriptive answers and opt instead to raise questions. What kinds of questions are you hoping the reader comes away with?

Kate Broad

This was exactly what I wanted—this feeling that what happens in the book shouldn’t have gone this way, and yet when you look back, where can you pinpoint the moment it all starts going wrong? It comes back to that Arendt quote, and the realization that where we wind up at the end of a life comes from a series of choices that link together in an endless chain. We always have the opportunity to make a different choice. And yet the more steeped you get in your life, the harder it is to opt out. Rachel should know better—but she doesn’t. Her family should help her—but they don’t.

It’s easy to look at these huge structures—capitalism, racism, an enormous wealth divide, entrenched gender roles, compulsory heterosexuality, the disproportionate impact of the carceral state—and say, well, I’m just one person, what am I supposed to do? And yet, as Rachel herself observes, the world is made up of people. We’re the ones who create and perpetuate these systems—we have freedom and agency even within these constraints. Why do we do what we do? Why do we hurt the ones we love? I don’t know the answers, and anyway a novel isn’t an essay—it doesn’t put forth a thesis it then has to prove. I just think these are questions we should all be asking.

Sara Maurer

Who do you hope reads Greenwich?

Kate Broad

I think all authors hope there’s a wide audience for their work! I’ve heard a lot from readers telling me that Greenwich made them think and gave them a lot to unpack. So that’s my ideal reader—someone who wants to sit with the book and consider it from different perspectives. It’s a big ask to expect someone to spend the hours it takes to read a novel, and I don’t take it lightly that someone would take that time to be with my words. Greenwich is for anyone who’s tried to figure out their place in the world, or felt pressure to be a certain kind of person or live a certain way. It’s for anyone who’s hurt others, or been hurt, and had to figure out a way forward. And anyone who likes page-turners about family secrets and rich people behaving badly—two things I can never get enough of. It’s been incredibly rewarding to see Greenwich find its audience. Writing takes so long and can be so solitary, so seeing the book move through the world is a new and really exciting experience.

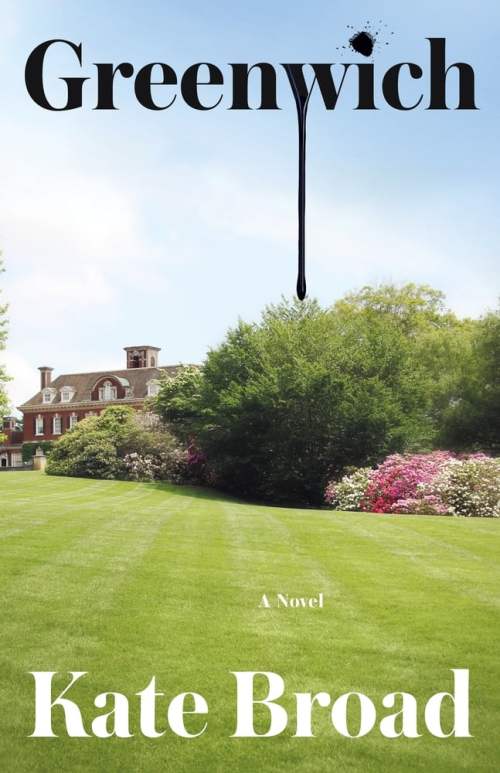

FICTION

Greenwich

By Kate Broad

St. Martin’s Press

Published July 22, 2025

Sara Maurer is a writer in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Place deeply informs her writing, particularly how it influences identity and choice. She was selected as a 2023 Suzanne M. Wilson Artist-in-Residence at the Glen Arbor Arts Center. Her debut novel, A Good Animal, which explores bodily autonomy in an agricultural setting, is forthcoming from St. Martin’s Press in 2026. Find her at www.saramaurerwrites.com.