It can be said that fables and fairy tales, such as those collected by the Grimm Brothers some two hundred years ago, are portraits of psychological growth. The Garden by Nick Newman is written as a modern fable, and very much follows this route. The narrative occupies what feels like a dream space. But unlike the chaotic and confused dream space of an existential novel such as The Orange Eats Creeps, Garden is framed by much older minds, ones that have lived in decades of set tradition. This space is a personally religious, almost animistic one, where trees are danced at to help produce apples, and the fear of a long-dead mother inspires virtually holy devotion to a gardening almanac—as well as an unconscious flagellation towards self and others.

Nick Newman is the pen name of Nicholas Bowling, who previously published several children’s novels. Garden was written while Newman sheltered in rural Scotland during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sense of isolation, timelessness, and loss of relation to other people influenced the writing of the novel. In literature, Cormac McCarthy’s descriptively scarce post-apocalyptic novel The Road has been cited as an influence, as well as Susanna Clarke’s modern tribute to Plato’s allegory of the cave, Piranesi. (It may be noted, additionally, that the story of the cave may be overlaid onto many self-development stories, including Garden.)

The protagonists of Garden are a surprising demographic: two elderly women. Evelyn and Lily’s circumstances are framed by a climate-induced apocalypse, their home an Edenic garden sheltered from destruction. They sleep in a single room of a mansion, forbidden by their mother long ago to break through the furniture and boards separating the rest of the house. Evelyn sets herself a strict work schedule around the garden to keep herself intact. Lily is more playful, an artist, and takes the work less seriously to focus on dancing and painting. Interstitial chapters reveal pieces of life from the sisters’ past, including the difficult relationship of their parents, formative memories that would build Evelyn’s later rigidity in life. In a home suffused with the sense that the sisters are the last of humanity, their isolated lives are interrupted by the appearance, in the midst of the garden, of a young boy.

There is a feeling of reversal here from the regular fairy tale, where the child ventures out and encounters a witch in a magical home. Although Evelyn and Lily are rich personalities and deeply sympathetic to the reader, it is not off target to read an archetype of the witch through them. Lily’s first instinct upon encountering the boy is to kill him. It takes Evelyn time to see him as little more than a “creature smell[ing] of dust and blood.” The boy remains nameless, an entity, a potential threat to life in the garden. Further revelations build on the witch archetype, but it is not the place of this article to spoil them for the reader. Like the mansion looming over the garden, Evelyn and Lily’s lives are a series of forgotten rooms, hiding both treasures and horrors.

Elements of the Gothic, speculative fiction, and suspense genres feed into the novel. The fog of time, memory, and unknown history personal and global twine these elements into psychological fable. Evelyn and Lily are well drawn as characters while the world around them is blurry and hard to see—and not just because of the blinding sunlight pervading the wrecked world. It can be observed that our lives are formed by our relationships, what we see is formed by who we interact with. Evelyn’s life is shaped by the memory of her mother, her living sister Lily, and more distantly the shadow of her disappeared father. For decades these relations have been the primary influence on her beliefs and choices, the formation of her fragile utopia. The boy that appears in the garden is a catalyst, breaking open Evelyn’s mind into a new world of considerations and concerns. She experiences shifts in relationship with Lily, tempted disobedience to the laws of her mother, and stirring ideas of the vast unknown outside of the garden.

Newman has suggested in an interview that dark aspects of masculinity are an important key to Garden, but it is difficult for this reader to see. Evelyn and Lily, two women, dominate the narrative. The nameless boy is a strong presence that disrupts their lives, but he is, after all, only a boy. Evelyn’s father, in his brief appearances, can be read as a symbol of patriarchy, but his role is limited. It can also be drawn out that the state of the world is due to the exploits of men, but this is very far from the action of the novel, and does not factor directly into the more interesting drama of Evelyn and Lily’s relationship. Nor does it factor, ultimately, into Evelyn’s personal growth and individuation.

The Garden is a solid speculative fiction read as well as fable. It’s possible that modern literature could use more intelligent adult fables, and the writer of this article would certainly like to see them. The late film director David Lynch often compared life to a dream in his works, a dream which fables can help us see more clearly. Beyond our daily structures, personal and social, our memories and fantasies shape the earth of our waking life. As Garden progresses, the brittle structures of ritual and time break up in ways both healthy and otherwise. The movement of life becomes a spiral, returning to the same situations from a higher vantage point. The personal soul, or the observing faculty, is the only constant.

FICTION

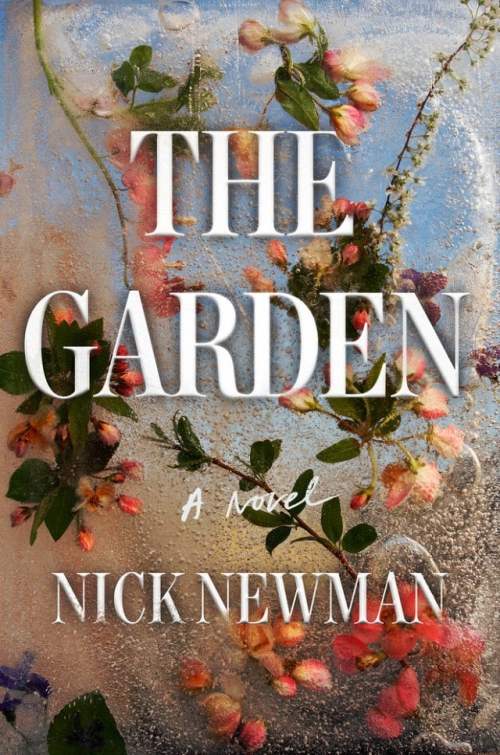

The Garden

By Nick Newman

G.P. Putnam’s Sons

Published February 18, 2025

Philip Janowski is a fiction writer and essayist living in Chicago. He is president of the Speculative Literature Foundation's Chicago Branch, a member of the Chicago Writers Association's Board of Directors, and a presenter with the late David Farland's international Apex Writers group. He has studied under such accomplished writers as Sequoia Nagamatsu, Martin Shoemaker, and Michael Zadoorian. His work in fiction has been awarded with an Honorable Mention from the Writers of the Future contest, and his major project is the upcoming Dominoes Trilogy. He can be reached by his Instagram account (@spiral_go), or by email at (philip@speculativeliterature.org).