If a novel can be likened to a painting, then Scottish author Ali Smith is a writer who knows that words, like pigments, are the atomic material of masterpieces. Sense emerges when words, those basic units of the socially defined project we call language, are positioned alongside other words, arranged into sentences; paradoxically, a single word in isolation is empty yet pregnant with potential. A single word, hosting a multitude of definitions and inextricable connotations, is powerful and unbounded, free to mean many things and nothing at once.

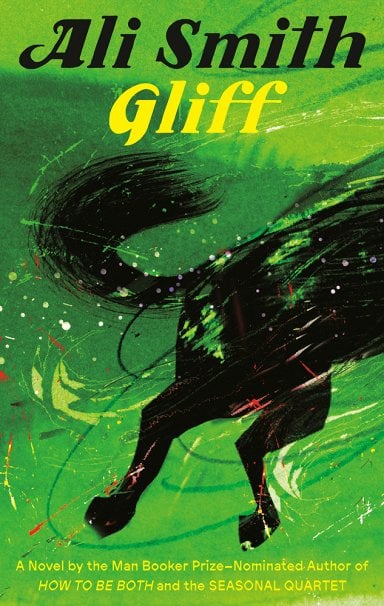

Such a linguistic gem is “gliff,” a Scottish word defined as a fright, a moment, or a glimpse, which serves as the title and thematic entry point of Ali Smith’s latest novel. Set in a near (and familiar) future where denizens live in a hyper-connected police state under constant surveillance, Gliff is a deceptively lean and impeccably crafted story. Equal parts bildungsroman and meditation on language’s entanglement with power, the novel is haunting and humorous, full of wit, wordplay, and references that run the gamut from eighteenth-century art to IBM. Smith’s genre-expansive work doesn’t stop at simply exploring identity and conformity under late-stage capitalism within its plot; fundamentally challenging the ways in which words are enlisted as tools of oppression, in which language is used to other, Smith shows us, one purposefully chosen word after another, that the redemptive side of language is art—its potential to break open rather than to bound, its ability to both redefine the world and exist within it.

Gliff follows a pair of enticingly precocious young siblings, Briar and Rose, who become separated from their mother after their home is repossessed and campervan impounded. The two are considered “unverifiables” by the sparsely rendered totalitarian powers that be; raised without access to network technology, Briar and Rose are not listed in the state data collection and surveillance system. The children find themselves alone and vulnerable, hiding from authorities and omnipresent cameras in a vacated home for fear of removal to a state-sponsored “re-education center.” After befriending a boy whose father raises abattoir horses for slaughter, Rose takes in a gelding she calls Gliff. Of this naming choice, Rose admits to Briar that she doesn’t know what the word means (“That’s why I like it,” she says with pitch-perfect earnestness)—but Gliff just feels “like its name should.” Soon after, the siblings make contact with a small community of unverifiables living nearby. With Gliff in tow, Briar and Rose move into an abandoned school with the others, trying to evade the omnipresent cameras while searching for their missing mother.

Written in first person from Briar’s perspective, Gliff splices together Briar’s childhood memories and life five years later. The novel’s temporally fractured narrative and voice-driven approach are ambitious but fruitful undertakings. The story reaches us filtered through Briar’s memory and worldview, while Smith’s prose slips seamlessly between Briar’s external and internal landscapes. Briar is the older of the siblings, and gender nonconforming—the reader learns this several chapters into the novel, when another unverifiable at the school named Daisy asks Briar whether they are “a boy or a girl,” and Briar aptly responds, “Yes, I am.” This is one of Smith’s masterstrokes, and a testament to the power of art to achieve what is, in reality, virtually impossible: because of the story’s first-person point of view, until this exchange Briar has been allowed to live on the page free from social constructions of gender. Briar’s refusal to self-define in a way that fits social convention is both compositionally and thematically at the heart of the novel’s interest in identity and names, and in Smith’s world, while language is employed as a tool of interpersonal and ideological control, words can also be means of resistance and self-actualization.

As the novel progresses, the reader learns Briar has at some point undergone the state’s abusive re-education process. In scenes from Briar’s present, where they work as an 18-year-old Day Shift Superior at the Packing Belt (a vaguely described, Kafkaesque apparatus on a floor called the Delivery Level), the act of telling is pulled into sharper focus. Given the constraint of first person, what Briar chooses to leave out of the story becomes vital to its overall shape and emotional center of gravity. At one point describing “voids,” unmonitored rooms in re-education facilities, Briar says:

The voids are where you learn what power does and what the word void can mean.

The void is simultaneously the place where, for me, words first ceased to mean and where, for words, I first ceased to mean too.

Over the past few years, most often at the start when I was still apparently fresh enough, I was repeatedly brought to various voids by men and women more powerful than me.

That’s as much of that story as I care to tell.

One line about it is more than enough.

Withholding the details of the abuse they face in the voids reflects Briar’s effort to repress their traumatic memories, and is another of Smith’s deft compositional moves. By deciding what to put into words and what to leave unwritten, Briar asserts agency over their experience through story. And, as contemporary readers, we are familiar enough with the kind of world in which Briar and Rose find themselves to still feel the weight of those narrative gaps—for those things which words can never render, only suggestion can come close.

While it is in many ways tempting to label Gliff a dystopian novel, following Smithian logic, to define the work as such would be to distance ourselves from some of the story’s most salient truths. To do so would also mean overlooking some of the important ways in which Smith subverts the conventions of the genre—concerned more with exploring the nature and usage of words than with tracing out an allegorical plotline, Smith offers us not a warning about times to come, but a path forward for the reality already upon us. Ultimately, Gliff calls us to engage critically with both the tyranny of language and the ways in which language allows us to redefine the world and ourselves. Like every story of resistance, it unfurls from a single word.

FICTION

Gliff

By Ali Smith

Pantheon

Published February 4, 2025

Devyn Andrews lives in Chicago and is a graduate of the UIC Program for Writers. Her work has been published in West Trade Review, Cutthroat Magazine, Memezine, and elsewhere.