Something Rotten is really quite good—enough that you half wish someone else had written it. The novel is Andrew Lipstein’s third outing in what has been a rather quick start, after Last Resort (2022) and The Vegan (2023). The story begins in New York, where the last two were set, but we are soon off to Denmark, where again the universal will be realized through some Nordic particulars. There is no sweet prince, but two credentialed professionals among their like: Cecilie, a business reporter for The New York Times, and Reuben, a former NPR host who was fired for an incident during a Zoom meeting, now an unhappy househusband looking after the baby, Arne. They are spending Cecilie’s maternity leave at her mother’s house in Vanløse, a suburb of Copenhagen. Rejoining her friends there, Cecilie learns that her ex, Jonas, has an inoperable blood clot in the brain—or at least something like that—but all the information is coming through Mikkel, a journalist whose crudeness Reuben finds appealing. Cecilie will have to speak to Jonas in person, while Reuben is drawn out of his megrim by Mikkel’s trickery and truth-seeking; both are glad of the time away from their compromised and cramped lives in New York. Lipstein had a good idea for a novel here. There was a spark or a shiver somewhere, and the characters are plausible, the plotting clever. But the epigraph from Saul Bellow makes you wonder what a writer with that kind of talent could do with these materials.

Something Rotten’s best quality is its thoroughness. Lipstein has worked hard at all his tasks: the heightened version of Reuben’s home life as he looks after Arne and waits for Cecilie to get home so they can leave for the airport; the account of what Reuben considers his “cancellation” done in installments, and Cecilie’s frustration with a scheming colleague; the quick profiles of friends Terese, Villum, and others, and the longer look at Mikkel, as part of a comparison of American and Danish customs; and everywhere, after every incident, Reuben’s or Cecilie’s anxious, probing thoughts, striving to understand every signification of clothing and speech, every possible consequence and motive. Through it all, Lipstein’s writing is mostly steady, though he falls into certain unhappy tendencies. On the local scale, his surest trick for thoroughness is to cover descriptive possibilities by listing them, and while the slightly nervy habit could be attributed to Reuben and Cecilie, between whose limited perspectives he alternates, this is also a pattern in other contemporary novels that stake a lot on observation. Sometimes it brings about redundancy, and elsewhere, it is as if the author is unsure of the subject. According to Reuben, that word cancellation “implied an effortless undoing, an act accomplished with a single click, a task that, once finished, could be forgotten for good.” The series of three, whether words or phrases, is a tempting rhythm, and elsewhere we can see more clearly that it is an easy format for Lipstein’s setting out of the options. The décor at a lovely place in the Frederiksberg Gardens is “tasteful, authentic, earned.” There Cecilie sees Jonas glancing over, and “this made her even happier, his company, his friendship, this warm togetherness.” The listing is certainly no way to treat a character: Arne, growing up so fast, is starting to act “coy, wry, impish even.” Novelists should choose the right word instead of hedging their bets on three, or better yet, show us their subjects in motion and draw out their features. Here is how Bellow, an expert animator, does it, telling us about Junie, baby daughter of Herzog: “giggling, twisting, splashing, dimpling, showing her tiny white teeth, wrinkling her nose, teasing.” Coy, wry and impish, and he has made them vivid. And how good are those “tiny white teeth”? These little details are missing in Something Rotten.

Bellow also tells us a lot about how his very educated characters think, and makes comedy out of the possibility that all their rational deliberation is futile. Lipstein is after some version of this, showing Reuben’s clever evasions vis-à-vis the brute facts that Mikkel might be delivering, but here too he slips into habit, one from which he ought to have satirical distance. Working for NPR, Reuben had heard a lot of HR language, but the shocks in Denmark should get him to stop speaking that way, and find out what he really thinks, if one’s broader understanding of the novel is right. As a sort of penitence he watches a recording of the notorious Zoom call, and pausing it, sees his disgrace in the expression of his colleague. Lipstein tells us straight out that this is an important facing down of the truth, and it will prepare Reuben to then tell Cecilie’s brother something very upsetting. But then he uses the same corporate, therapeutic terms that have surely been stifling Reuben all along, now turned to a muffled epiphany: “he had managed to supplant her lived experience with a narrative that ostensibly covered both of theirs . . . This was not only deeply unfair, it was strategically abstract, insulating him from the concrete impact of his actions.”

Thankfully, the strength of Something Rotten’s setup is enough to sustain it. There is suspense, and it is not only a question of what will happen in the end, but why, and what follows. The novel manages to illustrate something: that American college types are very cautious and polite, ironically as a consequence of a most competitive culture, one where things are not resented and fought in the moment but settled later in the courts. Mikkel has his personal reasons for his bluntness, but he is also the leader of the bantering Danes drawn for contrast with circumspect, circumcised Americans. (If you couldn’t tell already, Something Rotten is really Reuben’s story, Cecilie’s chapters notwithstanding). The novel is better on this smaller theme even while it reaches for the very biggest ones. Lipstein can’t go as particular as Bellow, largely because his English instrument isn’t as sensitive, and without those fine details he can’t get to the universals in the most thrilling, direct way, and instead can only hand out bulky packages for the book club discussion: mortality, masculinity, the nature of truth. These will do just fine, thank you.

FICTION

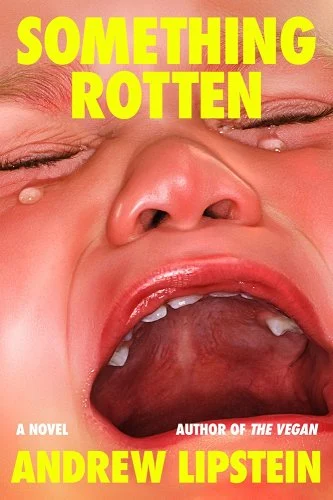

Something Rotten

Andrew Lipstein

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published January 21, 2024

Kazuo Robinson is a writer based in New York. His reviews have been published by The Adroit Journal, Cleveland Review of Books, The Oxonian Review, and The Millions. He maintains a Substack at kazuorobinson.substack.com where he writes about fiction.