Set My Heart On Fire is what would happen if Joan Didion wrote a tell-all memoir about her alternative, fictional life as a groupie. But not just any groupie — the Pattie Boyd of Japanese rock in the early 70s. The new English translation of the late Izumi Suzuki recalls Didion’s best reportage. Set My Heart On Fire reminded me of Play It As It Lays, Didion’s beautifully bleak portrayal of a young woman’s futile struggle for meaning and agency in the rarified world of 1960’s Hollywood.

Suzuki’s sizzling, posthumous novel is nothing if not bleak. Her narrator’s worldview is melancholic, nihilistic, highly sensitive, mercurial. She can’t help but please the men in her life, no matter how narcissistic or sadistic they are. She is damaged, yearning for love and yet unable to love herself, addicted to pills and at times seemingly suffering from an eating disorder.

It is 1973 in Yokohama, Japan, and 24-year-old Izumi’s modeling job provides her with an income and the latitude to do and feel whatever she wants. With an abundance of free time, she indulges a hedonistic lifestyle oriented around sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll—specifically, sex with up-and-coming band leaders, an addiction to sedatives like bromisoval, and a love of Japan’s “Group Sounds” era of blues and psychedelic rock influenced by western music of the time.

In chapters named after contemporary hits (I’m Your Puppet, Time of the Season, Keep Me Hangin’ On, and so on), Izumi uses mutual acquaintances to arrange meetings with the most attractive band members from the covers of her vinyl LP’s. Izumi bounces from one sexual liaison to another, enjoying each of them for their unique charms, even as she tolerates the arrogance and selfishness that comes with rock stardom. At the same time, all is not right with Izumi. Darkness lurks in the background, and her apathetic behavior and disregard for her own safety inspires genuine foreboding.

“The meds would kill me before long. Each night I gave myself up to those white pills. Or into the arms of a man… A man was a healthier choice. Pleasure from drugs was passive, but with sex it was something more active and distinct. I loved being treated gently and caressed. I liked the game, the back and forth. I also didn’t mind falling for them occasionally.”

It felt like a guilty pleasure to read Izumi’s encounters with her celebrity boyfriends. Who hasn’t wondered what it would be like to bed a rock star? But Suzuki’s sentences are so direct, her hook-ups so frankly recounted, that I often felt I had glimpsed the pages of a diary. These sex scenes are sensual and electric, charged with the boldness of erotic fiction and the terrible awkwardness of lived experience.

But her busy dating life grinds to a halt with the appearance of her soon-to-be husband. The outrageously entitled and sexually demanding Jun happens to be a genius free jazz saxophonist (Jun bears a remarkable resemblance to the author’s ex-husband, the doomed, avant garde saxophonist Kaoru Abe). But he is also possessive, jealous, sadistic, and mentally ill. Izumi seems bewildered by her own susceptibility to his obsessive advances (“I didn’t even like him, it was a pain being with him, but I was drawn in by some strange power that he and no other man had”). Their unhealthy, co-dependent relationship dominates the middle chapters of the novel, casting a dark cloud over the narrator’s life and sending them both hurtling toward a tragic end.

It would be easy to think of this as an edgy story about the sexual exploits of a boy-crazy groupie, but the first and final acts point to a more complex and transgressive reading. The first act portrays a young woman fantasizing over male idols, but what drives her is not naïveté, but ennui. The final act depicts a young woman, prematurely aged, physically and mentally scarred by her abusive marriage, disillusioned with her idols, and yearning to return to the carefree time of youth, before men began to control and manipulate her. From this perspective, the intense sexual encounters of the first act can be seen as an understandable but traumatic “bridge too far” for Izumi.

This reading prompts us to consider Suzuki as an important literary figure in the international women’s rights movement of the 1970’s and 80’s. Rather than writing a facile romance or even a more interesting rock odyssey, Suzuki chose to write a deeply disturbing, powerfully erotic, nihilistic confessional that unflinchingly challenges the predominant, traditional norms of post-WWII Japanese society; though the few facts we have about the author’s life make it impossible to deduce the date when the novel was drafted. All we know is that Suzuki wrote it before her suicide in 1986. Even if it was written in the mid-80’s, Set My Heart On Fire was undoubtedly ahead of its time. The ending offers an unsettling vision of women’s liberation in the era of globalization, mass media, and cultural exchange. The novel asks difficult questions about western values, sexual abuse, and the role that technology plays in advancing or stifling patriarchal systems.

Suzuki paints a three dimensional portrait of Izumi through a kaleidoscopic palette of nuanced and sometimes contradictory feelings about her male partners and life in general. At her most inscrutable, Izumi’s philosophical musings can be sphinx-like. But these cryptic pronouncements must be taken in context—they represent fleeting images and sensations that cohere into a story that western audiences might call autofiction but that Suzuki’s local audience would place in the older Japanese tradition of the “I-novel,” a related form predating autofiction and typified by the confessional aspect that defines Set My Heart On Fire.

All the more impressive, considering Suzuki has been known up until now as a writer of science fiction, a notoriously male-dominated field. Suzuki’s newfound exposure in the English-speaking world is thanks to Verso, the self-styled “radical” publisher that is complementing its largely nonfiction catalog with English translations of Suzuki. Who knows, maybe Set My Heart On Fire will earn a place in Verso’s “feminist classics” series alongside titles like Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World and Promise of a Dream: Remembering the 60’s. Regardless, it is very good news indeed that this snappy, plainspoken feminist novel is now available for English readers, too.

FICTION

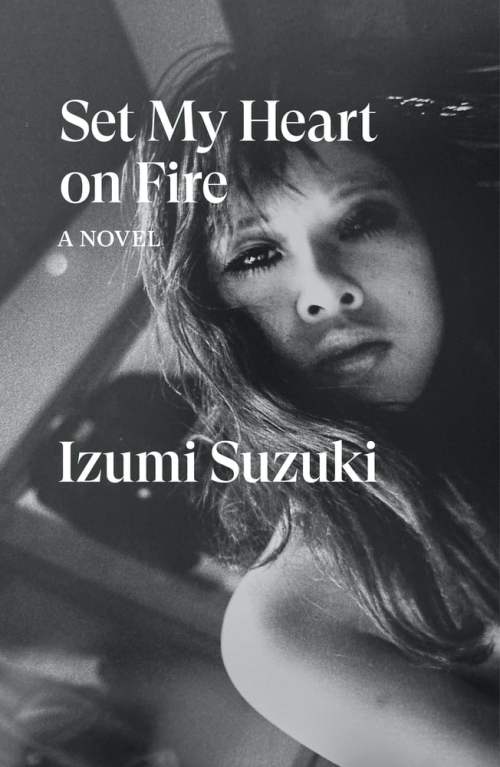

Set My Heart On Fire

by Izumi Suzuki

translated by Helen O’Horan

Verso Fiction

Published November 12th, 2024

Max Gray is a writer and artist of many stripes. His essays and criticism have appeared in the Chicago Review of Books and The Rumpus. He is a compulsive storyteller who often performs live on stage at The Moth in New York City. You can hear him perform and learn more about him at maxwgray.wixsite.com/max-gray