Vi Khi Nao is one of the most prolific experimental writers working today. She has published 34 books of poetry or prose since 2011. She frequently exhibits artwork and films. She has a substantial list of multigenre collaborations, not to mention an enormous list of uncollected stories, poems, translations, and essays. She’s like the Bob Pollard of indie writing, which as a Guided by Voices fan I mean as a compliment to both.

About halfway through Nao’s latest book, the autofictional novel The Italy Letters, the narrator (also a prolific writer named Vi) attends a conference and meets with a publisher, who recommends that she publish less frequently, both for economic and reputational reasons. When he asks why she publishes so much, Vi tells him that publishing books allows her to get rid of old ideas to make room for new ones, but later reflects that “what I meant to say without revealing too much about my existence or my mother’s existence was that my mother was suicidal and I wanted my book to economically explode so that I could give my mother the kind of retirement she desired.” Vi doesn’t explain her situation to the publisher, so she concludes that they failed to connect. “I don’t think the publisher understood my intent,” she writes, “because I could not, in my private, sad ways, explain to him why I was trying to flood the market.”

In the scene, Vi’s social and economic difficulties force her to keep parts of her life submerged. She has this experience frequently in The Italy Letters, such as when she recalls a years-long abusive relationship and notes that she had to “cut some of [her] memories off” to survive. Later in the book, Vi becomes romantically involved with a longtime acquaintance who uses Vi’s poverty to control her. Feelings of hatred and contempt build, but again Vi internalizes her emotions and reacts with silence and detachment. “I held all this in me, like a festered scar that wouldn’t go away,” she writes. “I kept my mouth shut, yet kept my distance.”

Given this pattern, it’s no surprise that Vi can’t explain her plan to the publisher. But what did she want to explain to him anyway? If her desire for her book to “economically explode” is the same as achieving financial success, why not take his advice seriously? What does it mean to achieve an “economic explosion” by flooding the market with books? Later in the novel, Vi writes that she wants to publish a bestseller, but then considers that she may have already published one, and that the book was “waiting for [her] permission to spread its achievement widely and it was on its way for its opulent triumph.” Again, Vi’s money-making strategy—sit back and wait for one of your books to unexpectedly make you famous—seems dubious. Plus, does experimental literature ever make anyone “opulently wealthy” anyway? In both of these scenes, Vi seems more invested in writing out a dreamworld than achieving real financial success.

This feels like an unforgiving interpretation of Vi’s character, but dreamworlds exist at all levels of The Italy Letters, and not always in negative ways. Vi spends most of the novel in Las Vegas taking care of her sick mother, who takes codeine and frequently drifts into states that Vi describes in enviable terms. Early in the novel, she writes that she loves Las Vegas because of “the fallen souls that bind their hopes to gambling.” More broadly, the novel itself consists of reflections on correspondence (letters, emails, texts, and more) between Vi and an unnamed friend who lives in London. Towards the beginning of the novel, Vi admits that she has private erotic longings for her friend, so the novel becomes a space to explore these feelings and the role they play in Vi’s life.

At one point, after a lengthy erotic fantasy about her friend (who is married), Vi wonders if her longings are healthy. “The point here was not to invite you to leave your husband, but for me to find my place in healthy desires,” she writes. “Is this healthy? Me fantasizing you this way? Or is this part of the cycle of heartache? What was my dream trying to tell me? That my heart was too old for you? Would I desire you this way you were single?” The gathering momentum of these questions makes it clear that danger lies ahead in the form of spiraling obsession. But the questions stop, and for the most part, Vi’s relationship with her friend throughout the novel seems helpful and supportive. The two friends encourage each other professionally, provide emotional reassurance, discuss literature, bond over their families. Vi often describes how she’s become “open” to new experiences and feelings through their relationship, specifically contrasting it with abusive relationships that have caused her to shut down or withdraw. If these interactions are motivated by Vi’s erotic dreamworld, then that world seems to be making positive contributions to her life.

The novel’s final section begins with what seems like the end of Vi’s relationship with her friend—Vi has recently ended a difficult romantic relationship and her grief leaves her unable to yearn or crave—perhaps portraying erotic longing as fleeting or unstable. But a page later, Vi texts to let her friend know of her arrival in New England. Less than twenty pages earlier, Vi had experienced a reflowering of passion. (“It came unexpectedly,” she writes. “I have come to learn that love could not be controlled.”) And we know from early in the book that Vi and her friend would occasionally go weeks or months without talking. Unlike other fictional works about erotic dreamworlds (Chekhov’s story “The Kiss,” for example), The Italy Letters refuses to criticize Vi’s longing as merely temporary, even if it doesn’t provide a happy ending.

In the book’s final scene, a woman tells Vi about “dream flow,” or the possibility of entering another person’s consciousness, but Vi rejects the idea because it seems invasive. Instead, she offers a vision of humanity as a deck of cards. “They get shuffled around,” she writes, “and if a 6 of Clover sat next to a King of Clover […] their temporary co-residency did not imply that they were destined to marry, to build a house of desire together, or even be remotely connected in some significant way.” The Italy Letters ends, in other words, by challenging two of the most cherished (perhaps the two most cherished) defenses of the social value of novels (otherwise known as dreamworlds): that they encourage empathy and provide us with structures of meaning. The scene recalls a recent interview with Vi Khi Nao where she resisted the notion that her writing creates change. Asked whether her collaborative book Human Tetris created a new place of humor and joy in her, she replied: “When I produce a work, I don’t view it as transformative. I see it more as an extension—an extension cord. You plug it into the wall, and it can get you only so far, and then you find another cord and add it to it, and you can listen to music a few miles down the road instead of where the outlet is.”

This concluding scene, this deflationary image of writing as mere extension—they aren’t enough to undo the glittering yet thoughtful imaginative work that Vi Khi Nao has done in The Italy Letters. (Vi was always so careful not to invade her friend’s consciousness with her erotic fantasies, after all.) But they are enough to make us reflect on what we’re doing when we talk about that work, package it into blurbs, publish it. They’re enough to encourage readers to try to choose the imaginative worlds they inhabit, rather than simply accepting those they’re given.

FICTION

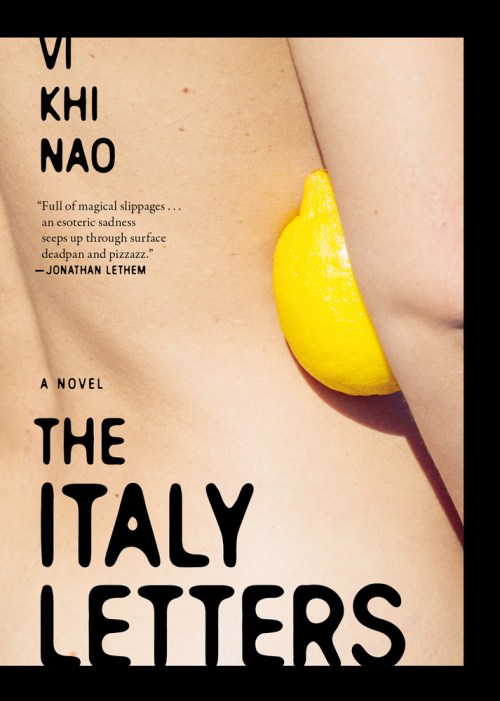

The Italy Letters

By Vi Khi Nao

Melville House Publishing

Published August 13, 2024

I teach English composition and literature at the University of Pittsburgh. I also review books for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Boston Globe, among others.