An American correspondent who covered the rise of Nazi Germany considered the Chicago Tribune’s Berlin bureau chief to be nothing less than “Hitler’s greatest enemy.” William L. Shirer, who reported from the German capital on the eve of World War Two, was also in awe of this journalist’s courage and resourcefulness. “No other American correspondent in Berlin knew so much of what was going on behind the scenes,” the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich would later note. “The best man we’ve got in Europe,” a Tribune colleague chimed in, even though she was a woman.

Meet Sigrid Schultz, the forgotten foreign correspondent who blew the whistle on Nazi atrocities, scooped the world with news of Hitler’s non-aggression pact with Russia in 1939, and defied the menacing thugs, bureaucrats, and Gestapo interrogators who tried to keep her from telling the truth. Hitler’s second-in-command Hermann Göring, who had the job of controlling the foreign press before taking over the Luftwaffe, dubbed her “that dragon from Chicago.”

Pamela D. Toler, who has a doctorate in history and has written ten books of popular history for children and adults, tells Schultz’s story in an engrossing, insightful, and deeply researched new biography. She rescues a pioneering reporter from the footnotes of history and recognizes her as one of the most important and influential American journalists of the twentieth century.

It’s a story that’s as inspiring as it is incredible. Born in Chicago, she was the daughter of Hermann Schultz who—despite the German-sounding name—was a portrait painter from Norway. While she considered the city to be her home, her family moved to Europe when she was eight and she grew up in Paris and Berlin, learning to speak German, French and a smattering of other languages that would make her such an effective foreign correspondent. When the First World War broke out in 1914, Schultz’s mother Hedwig was too ill to travel; the family was stranded in Berlin, where she witnessed the street battles that marred Germany’s transformation from imperial aggressor to a precarious postwar republic rife with warring factions.

Her big break came in 1919, when she attended a party and met Richard Henry Little of the Tribune, who established the paper’s first Berlin bureau and became her mentor. With her connections, local knowledge, and command of languages, she was a natural choice as Little’s “gunman”—slang for the combination of interpreter and cub reporter that a bureau chief needed to nail down the facts for the folks back home.

Schultz excelled in the role. “Energetic, nose for news, straight reporter, alert,” was the assessment one Tribune staffer offered to their boss, publisher Robert McCormick. She scoffed at the “junketeers” who parachuted in to cover the rise of the Nazis and “never ask embarrassing questions” or “report stories that might annoy the powers-that-be.” She prided herself on being immune to the “flattery, preferential treatment, boycott, and even threats” the Nazis used to intimidate the foreign press.

She took over the Berlin bureau in 1925 and remained one of the Tribune’s top European correspondents until 1941. For years she walked a fine line, pushing hard to expose the truth but knowing that she risked expulsion, Gestapo harassment, or even imprisonment if she revealed too much about Nazi preparations for war and Hitler’s genocidal plans. In 1931 she was granted a rare interview with Hitler and quoted his prediction that he would soon be supreme ruler, which proved to be accurate. Toler reveals how Schultz sometimes buried carefully worded references to concentration camps and crackdowns on Jews within seemingly harmless features to evade the Third Reich’s censors. She wrote some of her most critical reports under the pseudonym John Dickson, to give herself deniability when the inevitable complaints and threats rolled in.

Schultz fought other battles on the home front. She skirmished with editors who did not share her sense of the urgency and importance of exposing the dark forces engulfing Europe. And she endured the pervasive, casual sexism of the times and her male-dominated profession, even preferring to be called a “newspaperman” to better fit in.

The Dragon from Chicago also reveals what Schultz sacrificed to pursue her dangerous career and obsession with finding the truth. She never married. Her fiancé, a Norwegian sailor, died when a German U-boat sank his ship in World War One. A second relationship with another American foreign correspondent did not survive their long separations. A third man in her life was stranded in wartime Romania and then behind the Iron Curtain, and they never reunited.

“She was short in stature, tall in ideas,” recalled one colleague, and “tough when it came to digging out stories, and treating with frank skepticism every news release concocted in Joseph Goebbels’ Lie Factory, the Propaganda Ministry.” Toler offers a timely portrait of a journalist tailor-made to tackle today’s bitter political divide and rampant misinformation—a courageous storyteller smart enough to sort spin from fact and brave enough to tell truth to power.

NONFICTION

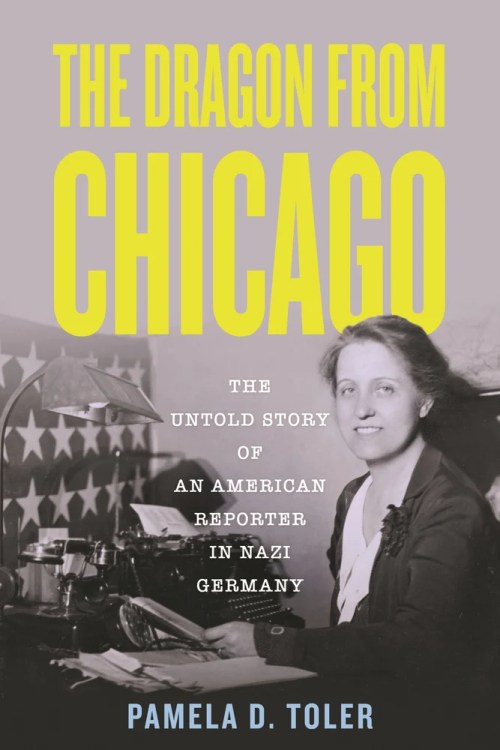

The Dragon from Chicago: The Untold Story of an American Reporter in Nazi Germany

By Pamela D. Toler

Beacon Press

Published August 6, 2024

Award-winning true crime author Dean Jobb’s latest book, A Gentleman and a Thief: The Daring Jewel Heists of a Jazz Age Rogue (Algonquin Books), is a New York Times Editors' Choice. It’s the story of Arthur Barry, who charmed the elite of 1920s New York City while planning some of the most brazen jewel thefts in history. He is also the author of The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream, which recreates the hunt for a Victorian era serial killer in Canada, Chicago, and England, and Empire of Deception, the story of 1920s Chicago swindler Leo Koretz. Dean writes a true crime column for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Website: deanjobb.com Facebook: Dean Jobb - True Crime Writer Twitter: @DeanJobb