Burning Worlds is Amy Brady’s monthly column dedicated to examining trends in climate fiction, or “cli-fi,” in partnership with Yale Climate Connections. Subscribe to her monthly newsletter to get “Burning Worlds” and other writing about art and climate change delivered straight to your inbox.

Across the country, and indeed around the world, college instructors are adding works of climate fiction to their syllabi. To discover more about which books are being taught, and what kinds of questions they’re inspiring in the classroom, I reached out to Elizabeth Rush, a visiting lecturer in English at Brown University—she recently taught a climate fiction class. She is also the author of the beautiful and urgent essay collection, Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, coming this June from Milkweed Editions.

The works that Rush teaches in her climate fiction course vary widely in style and content. That’s because the world they represent is so wide-ranging: “Cli-Fi is undoubtedly tied to a set of contemporary anxieties about human beings and their relationship with the environment and technology,” she writes in her syllabus.

Her syllabus also outlines a set of fascinating questions that frame her course: “What…does it mean that [climate fiction] has one foot firmly placed in the present tense? How can we distinguish [climate fiction] from its predecessors? And in what ways does fiction create an imagined world that gives voice to resistance now?”

This focus on not only climate fiction’s reflection on–but its influence of–the present moment suggests that the genre has a social purpose that goes beyond mere entertainment. That’s an inspiring—if robust—view of what literature can do, and one that I hope to continue investigating in future columns.

In the meantime, I asked Rush to recommend some of her favorite works of climate fiction (novels and short stories) to both read and teach—and to explain why she chose them. Her responses are below.

*

“The Tamarisk Hunter” by Paolo Bacigalupi

“One of the things that interests me most about climate fiction is how often it is deeply informed by real science and the history of human beings bending our surroundings towards our will. Before Paolo Bacigalupi wrote The Windup Girl and Ship Breaker he wrote nonfiction for High Country News and other outlets. He turned to cli-fi in order to reach a broader audience but that didn’t mean he turned his back on one of his favorite topics: drought and water management in the American west. While I respect the overt references to Cadillac Desert––that encyclopedic history of the (mis)management of the Colorado River––sprinkled throughout his most recent book, The Water Knife, I have a hard time assigning it because it’s a very violent text. Instead I have my students read one of Bacigalupi’s early short stories, ‘The Tamarisk Hunter.’ ‘The Tamarisk Hunter’ tells the tale of Lolo, a twenty-second century cowboy, who makes a living schooling the system in a drought-ravaged and oppressively-policed Utah-to-come. Those in charge of stockpiling water for California force Lolo from his land, reversing the settler stories and frontier narratives that have long defined our nation.”

Gold, Fame, Citrus

by Claire Vaye Watkins

“Speaking of drought, Claire Vaye Watkins’ hallucinogenic book Gold, Fame, Citrus also tells the tale of a west without water. California has become a dust bowl and those who once flocked there in search of stardom and ore now flee in the opposite direction. On the surface it’s a road book, with the two central characters––Luz, a former poster child for water conservation and washed-up model, and her boyfriend Ray, a soldier-turned-surfer-turned-survivalist––leaving Los Angeles in a beater car with a stolen toddler in search of someplace better. However, on a deeper level Gold, Fame, Citrus is a meditation on the cult of consumerism that feeds off of Hollywood and its celebrity culture. Watkins’ 1000-watt prose––radiant, potent, and brimming over like the aisles of a big box store––set this book apart. Sometimes I find myself needing to read aloud from Gold, Fame, Citrus, just to get the energy of Watkins’ sentences into the classroom. For instance, she describes the giant dune that shapes the second half of the book this way, ‘Still came sand in sheets, sand erasing the sun for hours then days, sand softening the corners of stucco strip malls, sand whistling through the holes bored in the ancient adobe of mission churches.’”

“Monstro” by Junot Díaz

“Díaz’s ‘Monstro’ takes place on Hispaniola (the island comprised of Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in the not-too-distant-future where record-breaking heat fuels the spread of a fatal fungal disease known as la Negrura (or The Darkness). For a while la Negrura is largely ignored, precisely because it afflicts the most vulnerable members of the population first, most of whom predictably live in Haiti. I am often inclined to read the disease itself as a stand-in for climate change writ large, the thing that initially decimates the poor and the weak while the rest of us look away. Our narrator, who is from the D.R. and returns after studying at an east coast Ivy, largely does the same, catching voyeuristic glimpses of the diseases’ destructive outbreak via text. He is too busy hanging out at rooftop parties and chasing a girl to care. As time wears on the disease starts to draw those suffering together into groups, some physically fuse with one another, all start shrieking in unison. The possibility of emancipatory violence hangs in the air. I don’t want to give the ending away so I will stop there. Suffice to say that the world cli-fi characters occupy often looks uncannily a lot like earth and the one that Díaz imagines is no different––the inequalities of today amplified thanks to resource scarcity and extreme weather. What ‘Monstro’ gets so very right is that it digs into the complicated relationship between race, class, and climate change; and how unequal power distribution shape what Díaz calls ‘our unthinkable present’.”

New York 2140

by Kim Stanley Robinson

“Everywhere that is located less than fifty feet above the highest high tide today is underwater in the world Robinson depicts in his most recent book, New York 2140. Franklin (one of the protagonists featured in work’s eight interwoven narratives) has created WaterPrice a ‘Intertidal Property Pricing Index’ that assess whether the value of this littoral land is rising or falling, and then allows investors to make bets on its projected worth in the future. In this way, the Wall Street of the future takes its cues both from the circumstances that shaped the recent housing crisis and the rise of commodity index trading. In New York 2140 financial instruments continue to transform seemingly ‘illiquid’ physical objects (like half-sunk office buildings) into a kind of currency, divorcing the thing itself from its value. New York 2140 is a speculative, but deeply researched, rendering of the future that understands late stage capitalism not as immutable, but the product of a complicated set of power relationships that are often articulated through economic means. Many of my students don’t really remember the crash of 2008, and so this book can both serve as a jumping off point to discuss the nuts and bolts components of our current financial system, its history, and how we might begin to imagine the circumstances and actions that will weaken this institution in the future. Plus, few do world-building better than Robinson.”

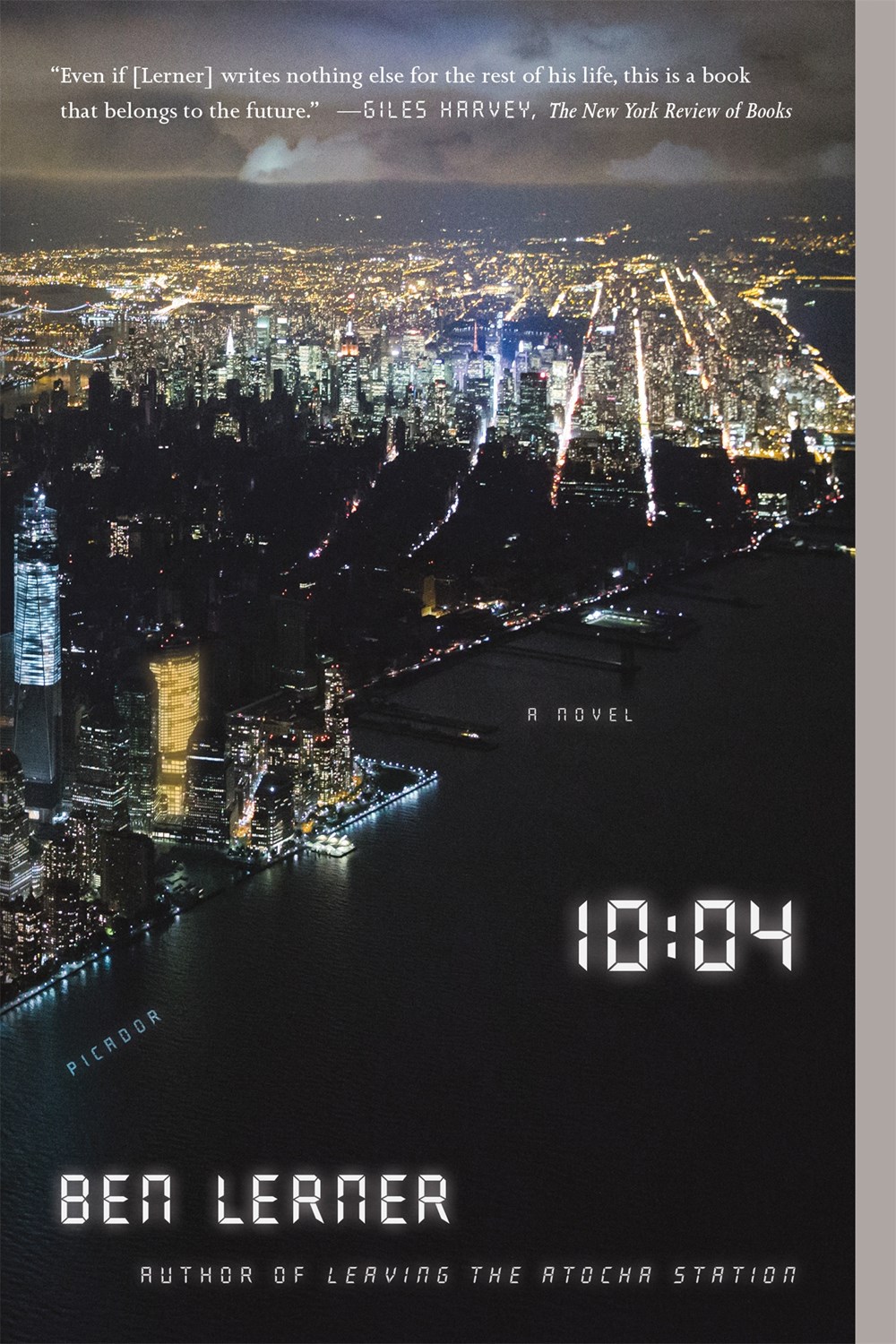

10:04

by Ben Lerner

“Rounding out my list is Ben Lerner’s not-so-speculative 10:04. It too takes place in Gotham. But in 10:04 the storms are real. The narrator––a white, hipster novelist and Lerner’s avatar––prepares for Hurricane Irene by making a pilgrimage to the mostly ransacked Whole Foods on Union Square observing, ‘The relative scarcity was strange to behold: in what were typically bright aisles of superabundance, there were now large empty spaces, especially among prepackaged staples, although plenty of outrageously priced organic produce still glistened in the artificial mist.’ What I most admire in Lerner (in addition to his poet’s powers of perception) is his refusal to make Hurricanes Irene and Sandy dramatic. Instead, the drama––what little there is of it 10:04––is almost all internalized. Our deeply obsessive narrator, who wants community but can’t seem to see beyond himself, spends most of his time thinking about whether or not to ‘construct’ a child with a close female friend who has asked him to donate his sperm. At the book’s close he rides out Sandy in his apartment while projecting Back to the Future on the bare wall across from his bed. The lights flicker but power is not lost, at least not in the narrator’s neighborhood. The refrain ‘Everything will be as it is now, just a little different––’ returns often in 10:04, reminding us that the little we do makes us complicit in the future we, like Lerner’s narrator, continue to construct.”

NONFICTION

NONFICTION

Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore

By Elizabeth Rush

Milkweed Editions

Published June 12, 2018

Elizabeth Rush’s journalism has appeared or is forthcoming in the Washington Post, Harper’s, Guernica, Granta, Orion, and the New Republic, among others. She is the recipient of fellowships and grants including the Howard Foundation Fellowship, awarded by Brown University; the Andrew Mellon Foundation Fellowship for Pedagogical Innovation in the Humanities; the Metcalf Institute Fellowship; and the Science in Society Journalism Award from the National Association of Science Writers. She received her MFA in nonfiction from Southern New Hampshire University and her BA from Reed College. She lives in Rhode Island, where she teaches creative nonfiction at Brown University.

Help the Chicago Review of Books and Arcturus make the literary world more inclusive by becoming a member, patron, or sponsor. Each option comes with its own perks and exclusive content. Click here to learn more.

Amy Brady is the Editor-in-Chief of the Chicago Review of Books and Deputy Publisher of Guernica Magazine. Her writing has appeared in Oprah, The Village Voice, Pacific Standard, The New Republic, McSweeney's, and elsewhere. Follow her on Twitter at @ingredient_x.