Before being the youngest woman elected to statewide office in Michigan, Mallory McMorrow was a remarkably unremarkable cis, white, heterosexual woman. This fact is key to the project of her memoir, Hate Won’t Win. Her early Senatorial career was plagued with the constant rearing of so-called “culture war” issues, intensifying until a rival within the Senate called her a “groomer” because of her support for LGBTQ+ children. McMorrow pushed back forcefully with a speech on the floor of the Michigan State Senate that went viral.

There’s no denying that McMorrow’s story is significant in this moment of political discontent. The title of her book, Hate Won’t Win, is drawn verbatim from the speech that launched her into the political spotlight. The earliest parts of the book are focused on the normalcy of McMorrow’s pre-political life. Hers is the story of someone who never aspired to political office, and this is the central crux of the book.

Divided into three parts, the book is one part memoir, one part call-to-action, and one part workbook. Its aim is to inspire other average Joes and Janes to political involvement. The first section chronicles her life up until the point of her election. The second section provides actionable advice for other regular folks to get involved, illustrated with anecdotes from her life in public office. The workbook section offers readers the opportunity to really dig into their political identities and plan their next moves. In its attempt to appeal to some amorphous everyman, the book suffers from a lack of clear direction. There are gestures toward bipartisanship that come across as more not-like-other-Democrats than a genuine attempt at conciliation.

In many ways, McMorrow’s path to election is the least interesting thing presented, and it’s done twice: once in the form of a quickly summarized introduction and again across the first three chapters in more detail. As impressive as it is to get elected at any level of government, the real inspiration of her story lies in what she was able to accomplish once she got there, and so much of that content—her entire first year as a legislator, for example—is missing in favor of the drama of electioneering.

McMorrow’s insights are never more prescient as when she explores specifics of women’s issues. During her first term, she became the first pregnant Senator in Michigan and was forced to advocate for herself in an institution with no mechanism for maternity leave. Her pregnancy came at a time when scores of millennial new moms were being radicalized into the alt-right through medical skepticism on social media. The way her allegedly pro-life opponents tried to use her missed votes against her and the way she was able to overcome these challenges are some of the most interesting sections of the book. Unfortunately, these elements are relegated to a single chapter. With a stronger throughline in the life story sections of the book, the text would be more coherent with a more natural audience.

McMorrow’s advice is often solid and actionable: consume less political media, stop doomscrolling, and do something. She lambasts the use of online petitions and form emails to elected officials as not going far enough, telling readers to call or show up to offices in person to have their voices heard. The vast majority of her advice is simple and key: despite the constant focus on national politics, the areas regular folks have outsized impact to create change is at the state and local levels.

Attempts at appearing bipartisan occasionally hamstrings the advice. Insisting that both sides have problems while pointing out that Republicans were responsible for unspeakable amounts of violent misogyny—sexual harassment of lawmakers, an attempted kidnapping of Governor Gretchen Whitmer, the accusation of “groomer” that launched her political star in the first place—dilutes the power of those points. Issuing blanket condemnations of protests and referring to marginalized groups’ attempts to tell their own stories as “taking the bait” alienate some of the demographics who would otherwise be best served by a book like this.

Overall, Hate Won’t Win is attempting to do something quite interesting in the political memoir space. McMorrow’s use of her own life story is somewhat muddled and unfocused, leading to some redundancy and some skimming over of truly important and unique perspectives. Her advice and workbook prompts might be what her intended “average American” reader needs to get involved themselves, but provides little for the already politically engaged.

NONFICTION

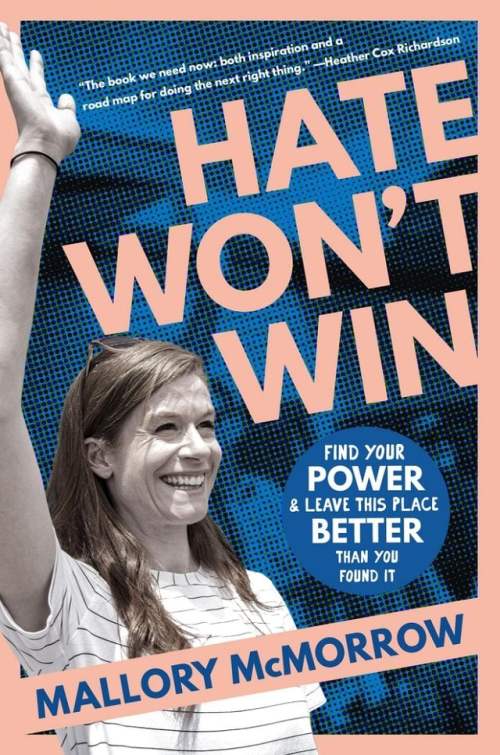

HATE WON’T WIN

By Mallory McMorrow

Grand Central Publishing

Published March 25, 2025

Christopher Bigelow is a trans writer, former teacher, and metadata manager living in Chicago. He writes about the intersections of queerness, trans identity, the public school system, the full range of human emotion, and sometimes outer space. His work has appeared in such outlets as Tension Literary, Collider, and the Chicago Review of Books.