Yasmina Din Madden’s debut short story collection, You Know Nothing, alternates between painfully realistic and spectacularly strange, frequently dragging the reader into a vivid, intriguing new story only to boot them out soon after. Through the 41 stories in this collection, the author takes serious interest in women and their bodies, the many iterations of motherhood within the same life and across different ones, mixed-race Asian identity, and shapeshifting grief. Madden lets visceral, tangled-up emotions shine with unwavering, clear prose that manages to immerse the reader immediately into the handful of paragraphs that sometimes comprise the entire story.

Several of the stories feel like the kind of interstitial memory that many of us could dredge up from childhood that suddenly takes on new weight when examined through the weary eyes of an adult. Two half-Asian, half-white boys wear and bear their racial identities differently in “A Gook, Not a Chink,” while a first-person plural narration recaps rumors about a high school math teacher sleeping with a student in “X + Y = Something,” and a teenage girl lives through a devastating heat wave and an almost sexual assault in “Heat.” Even at the time, these characters feel uneasy about what has or might or nearly transpired, but Madden excels at allowing space for the audience to fill with concern. When you’re young, so much of your world is understood through comparison against your peers, like the observation in “A Gook, Not a Chink,” that “… in Max’s family it’s like the white blots out the Vietnamese, whereas in Nitz’s the white is just a background on which to paint his mother’s Korean-ness.” There is so much contained in that statement that the reader is aware those boys will not engage with until years from the story’s end.

Repeatedly, Madden hones in on the uncanny feeling of someone being racist towards you but not even doing it right, revealing themselves as doubly ignorant. In “Neighborhood Watch,” to the neighbors of the Asian wife of a white man in 1970s suburban America, “the only thing she can possibly be to her neighbors is a war bride. An intruder. A gook or chink.” A neighbor accuses her husband of working for the state and then threatens to report him? Lily recalls her Vietnamese mom being called “a lazy Filipina” in “Heat.” This experience of incompetent racism is especially common for Southeast Asian immigrants, who come from countries ravaged by American geopolitical machinations that white Americans never even bothered learning the names of and stereotypes for. In “Naming Things,” a girl named Leila recognizes that a question about the origin of her name is a thinly veiled question about her race and remembers previously being inaccurately identified as Hawaiian. There’s little utility in offering a correction but the temptation is there. It’s a cutting reminder of why “Asian American” remains a relevant political category and basis for solidarity.

A number of Madden’s stories involve the same characters from a Vietnamese American family with relatives in France. The mother in the family is sometimes the mother, banging her head on the wall (“Then Go to Paris, I Say”), but she is also Five, the fifth child of twelve who leaves Cambodia to study in Madrid (“Five Things You Should Know About Five”). The slow piecing together is satisfying, and the sense of surprise when the characters make return appearances in new forms is a reminder of how long and winding life can be. None of the characters themselves will ever have the opportunity to perceive each other in the full range that the reader gets to. Madden depicts Lily and Margot as young witnesses to their mother’s rage (“Splinter”) and also as adults living distinctly divergent lives in “Rococo.” These glimpses can feel like ghosts, the stories that follow each character around, that they fear others define them by.

Amidst vignettes that feel wildly plausible, Madden intervenes with a demand to suspend your disbelief. Turn the page and, like a test to see whether you’re paying attention, the story “Georgia Simpson” starts when the titular character wakes up, “tangled in the blue sheets of an unfamiliar bed, she finds herself transformed into a giant slippery slug.” The writing is matter-of-fact in a way that makes the speculative elements reasonable, even when “what was once [Georgia’s] shoulder.. is now just part of the sloping mass of her rubbery moss-colored body.” Madden delights in making our already grotesque beauty standards more grotesque with “Trimmed,” a tale about a woman who realizes she no longer experiences pain and immediately starts going under the knife.

Across all the stories in this collection, You Know Nothing continually insists upon its title. It’s the sort of phrase your parents say when they wield their age as wisdom over you (as Lily and Margot’s mom does in “Splinter”), that you hurl at a significant other during a vicious spat, and that you laughingly affirm about your past self in hindsight. Madden’s storytelling is invested in the idea that, as she puts it in “Zero-Sum Game,” “the absence of something is a thing in and of itself.”

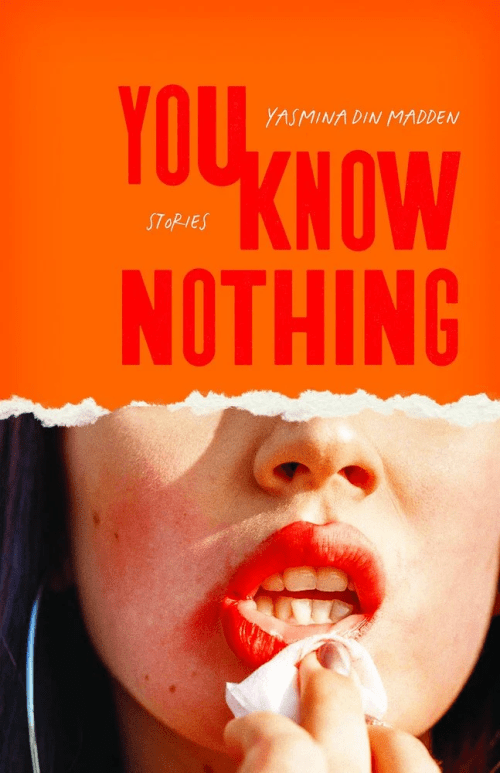

FICTION

You Know Nothing

By Yasmina Din Madden

Curbstone Press

Published February 15, 2026

Anson Tong (she/her) is a writer, photographer, and behavioral scientist based in Chicago. Her work has appeared in Chicago Review of Books, Chicago Reader, The Brooklyn Rail, Joysauce, The Rumpus, The Millions, and Stanford Social Innovation Review. She writes a newsletter called Third Thing (thirdthing.substack.com), which has no theme and more than three things. She was a 2023 Zenith Cooperative mentee. You can find her website (and her Bluesky!) at ansonjtong.com.