She is a babysitter, an astronaut, a prom queen, a Marine Corps sergeant, and the President of the United States. She is a sex object and a sexagenarian. She’s been coveted and collected, decried and destroyed. Like many in my generation, I took great pleasure in ripping off her head. She, of course, is Barbie, and her almost seven-decade life story, so to speak, is the subject of Tarpley Hitt’s deeply researched and wildly entertaining new book Barbieland: The Unauthorized History.

In chronicling Barbie’s ascent from a ripoff of a German doll to an inescapable cultural icon, Hitt also traces the evolution of post-World War II American capitalism. Along the way, she introduces readers to a bevy of colorful personalities, from Ruth Handler, Barbie’s brash, scandal-dogged inventor, to Jack Ryan, the hard-partying, womanizing toy designer whose second wife was Zsa Zsa Gabor.

Hitt, whom I met in college, is a writer and an editor at The Drift. We spoke over Zoom about recycled IP, Osama bin Laden dolls, and AI slop.

Angela F. Hui

You’ve written about a lot of different topics—politics, horse racing, and XXXTentacion, to name a few. What made you decide to write a book on Barbie?

Tarpley Hitt

I’ve always been a generalist, but to the extent that I’ve had a beat, I would say it’s mostly been at the intersection of culture and money. When the Barbie movie was announced, I’d been thinking about the number of media properties that were remakes or reboots or adaptations of recycled IP—I was working, at the time, for a website [Gawker] that was itself a piece of recycled IP—and I felt like maybe the culture was moving past that. There was such a widespread exhaustion with reboots. So I was taken aback by the genuine excitement around the movie.

I knew that Barbie was not only a piece of familiar IP but a piece of stolen IP, that she’d been based on a German doll, Bild Lilli, that wasn’t a sort of similar fad toy, but an identical doll that had been extremely popular, extremely famous, and had itself been adapted into a movie in 1958. I was interested in what made a knockoff doll exceed an original that’s already popular, and why Barbie resonates with people so much, both positively and negatively.

A friend of mine who’s in his sixties was saying that when he goes to the toy store to get a toy for his grandkids, the ones he recognizes from when he was in elementary school are the rubber ball, the slinky, and Barbie. We have all these flash-in-the-pan toys like the Labubu that start a craze and become a sensation but sort of burn out after two to three years. (I’m calling it now, the Labubu thing will be over soon.) But that really struck me, that Barbie is the one toy that just never goes away.

Angela F. Hui

How did you figure out which parts of Barbie’s history to focus on?

Tarpley Hitt

I wanted to write about the arc between two lawsuits: the one where the creators of Bild Lilli sued Mattel, saying, “You’ve stolen our doll,” and the one almost fifty years later, when Mattel sued the makers of Bratz, saying, “You’ve ripped off our doll that we, in turn, ripped off.” I was thinking about those two poles, and how this doll that begins as a replica becomes enough of an institution that’s something not even that similar to it is argued to be a knockoff.

Between those two poles, I really wanted to focus on episodes in Barbie’s history that underscore how the story of Barbie is also the story of how the post-New Deal, post-World War II American economy desiccated into this oligarchic, corporate-controlled, quasi-monopolistic economy that we’re living through right now, and how Barbie both anticipated and participated in the economic trends that brought about that transition.

For instance, Barbie was never manufactured in the US. It was one of Mattel’s first offshored projects, and so there’s Mattel embracing offshoring before much of the corporate world. There’s Mattel’s revolt against federal regulation in the sixties and seventies, and their embrace of the Reagan eighties’ financialization-leveraged buyout situation. And then, of course, their full-throated support of things like NAFTA and China’s Most Favored Nation status in the nineties, which brought about many of the trends that Trump is now haphazardly trying to reverse via his tariff plan.

Barbie is also an interesting cipher for the times. Part of Barbie’s appeal, and part of how this doll has had so much staying power, is that Ruth Handler envisioned her as a blank canvas, with no personality and not much of a backstory, so she could very easily be adapted to different contexts. You can see social and economic developments from the mid-twentieth century to the twenty-first century reflected, in microscale, through her outfits or through the new jobs she acquires.

Angela F. Hui

The Barbie movie came out while you were working on the book. Was there anything about the movie or its reception that surprised you?

Tarpley Hitt

The sheer size of the craze surprised me. Movie theaters nationwide had been struggling since the pandemic, and there was panic in the film industry about whether or not people would go back to the movies. And then the turnout for the Barbie movie was honestly shocking.

I think part of it was that unlike so many other toys, which have elaborate backstories and lore to draw from, Barbie has very intentionally been blank the whole time. Even the details that Mattel has accepted—that her last name is Roberts, or that she’s from Willows, Wisconsin—even those details weren’t in the movie. Because they had this blank doll, the movie was in some ways a piece of original IP, because there was no story, and Greta Gerwig wrote it from scratch.

Angela F. Hui

Given all the research you’ve done on Ruth Handler, I’m curious to know what you thought of her depiction in the movie. How would you have depicted her, if you were making your own Barbie movie?

Tarpley Hitt

She would have been a little more evil—not to say that she was evil, but she was not a sweet, heavenly grandma who exists in some sort of ethereal kitchen. She was a ball buster who could be very cutthroat and was very explicitly not feminist. She not only avoided that term but wielded power in a way that did not welcome other women to share her level of success. I’m thinking specifically of her service on Nixon’s oversight committee, where she was advising the White House on how to respond to a new set of employment guidelines. Some of the advice she gave was to scrap a section encouraging companies to offer maternity leave and to remove references to hiring minorities.

Also, the thing that gets me is her zinger in the movie about having trouble with the IRS. She didn’t have an IRS problem. She had an SEC problem because she was tried and convicted of fraud, which is totally different than getting audited on your taxes.

Angela F. Hui

In the book, you write about how secretive and almost impenetrable Mattel is, as well as their history of using litigation, or the threat of litigation, to control Barbie’s image. While you were writing, were you ever worried that they would try to shut you down?

Tarpley Hitt

Totally. I’ll just say there was a thorough legal read.

For context, Mattel was one of the most litigious companies of the nineties. The problem with Barbie being so adaptable, and so omnipresent in the cultural zeitgeist, is that it becomes low hanging fruit for jokes. There’s all these different parody Barbies you can make, because you can make Barbie anything. This artist Paul Hansen in San Francisco made Trailer Trash Barbie and Drag Queen Barbie, and others that were more crude as well. At the same time, this is a children’s product, so the company was quite concerned with there being any depiction of this blank canvas that wasn’t focus-grouped and hyper-controlled. They sued Hansen, they sued another artist, Tom Forsythe, who did portraits of Barbie and various kitchen appliances, and they went after random online zines to try to control the image of the doll.

But it didn’t look great for them, especially when they sued over Aqua’s song “Barbie Girl,” which is clearly a parody. They appealed to the Supreme Court, and suddenly it became a national story, which was not ideal PR for them.

Angela F. Hui

I’m wondering if the Barbie movie represents a shift in Mattel’s PR strategy. They used to shut down even fairly mild criticism, but the Barbie movie itself has some jokes at Mattel executives’ expense.

Tarpley Hitt

In the nineties, they seemed not to get that their aggression towards criticism seemed to affirm the critique. Now they no longer bring quite so many frivolous lawsuits. And part of their pivot, with the movie, was realizing that if they partnered with the critics, then they could make money even from people who were critiquing them.

Angela F. Hui

Was there anything you wanted to include in the book but didn’t have space for?

Tarpley Hitt

There were a few things I wanted to get into but couldn’t quite fit in. One that comes up briefly is the human Barbie situation, the people who get surgery to look like Barbie.

There’s another thing I really wanted to include but didn’t, because it’s ultimately unrelated, despite how nicely it fits in with Mattel’s early proximity to defense contractors. After 9/11, the CIA contracted with this former Hasbro executive named Donald Levine, who was one of the designers of G.I. Joe—which, by the way, was totally inspired by Barbie, as a male non-doll that could have many accessories. Anyway, they contracted him to design a doll that would be Osama bin Laden, but it would turn into a demon when exposed to heat. They were going to ship these dolls to Afghanistan and Pakistan, and then in the warm climate the paint on bin Laden’s face would peel off to reveal a Darth Maul-looking scary devil. The idea was literally to terrify innocent children into disliking Osama bin Laden.

Angela F. Hui

One of Mattel’s biggest fumbles was its attempt to keep up with the “digital revolution” by acquiring The Learning Company in 1998. What more recent attempts has the brand made to adapt to a new technological landscape?

Tarpley Hitt

Mattel actually partnered with OpenAI earlier this year. It’s ironic given Mattel’s history of intellectual property litigation, though they didn’t surrender any of their IP in the deal.

It reminded me that in April, there was this huge trend on LinkedIn of people using ChatGPT to create personalized AI Barbie boxes for themselves. It was baffling to me as a trend, because it looked horrible—all AI slop, in my opinion, looks pretty horrible. These were bland, cubicle-looking boxes that had someone’s vague likeness on the doll’s face, but the trend totally took off. These were completely unlicensed AI Barbies, and then a few months later, Mattel announced the OpenAI partnership. Instead of suing over unsanctioned use of Barbie IP, it was—much like the movie—another instance of aligning themselves with the people they would otherwise sue.

Angela F. Hui

What is the OpenAI deal actually for?

Tarpley Hitt

Unclear at the moment. I think they’ll be using OpenAI internally for product development, and potentially in their expanded entertainment empire. Mattel’s CEO keeps saying they’re pivoting to an entertainment brand, that instead of consumers they have fans.

Angela F. Hui

What does it mean, exactly, for Mattel to say they’re an entertainment company?

Tarpley Hitt

They have a lot of films in the works. They’re trying to turn basically every toy into its own movie. The most high-profile one is the Barney movie, which Ayo Edebiri is writing the script for. They described it as a gritty A24 movie, though I suspect with Ayo’s touch it’ll be more of a goofball comedy. They’re doing a He-Man movie, a View-Master movie, an American Girl movie, and at one point there was going to be a Polly Pocket movie that was going to be written and directed by Lena Dunham, but she left that project. The idea is that they’re going to license basically every product in their toy chest and turn it into a movie.

My suspicion is that the Barbie movie was actually singular and that this recipe cannot be replicated for every single toy. But I guess we’ll see.

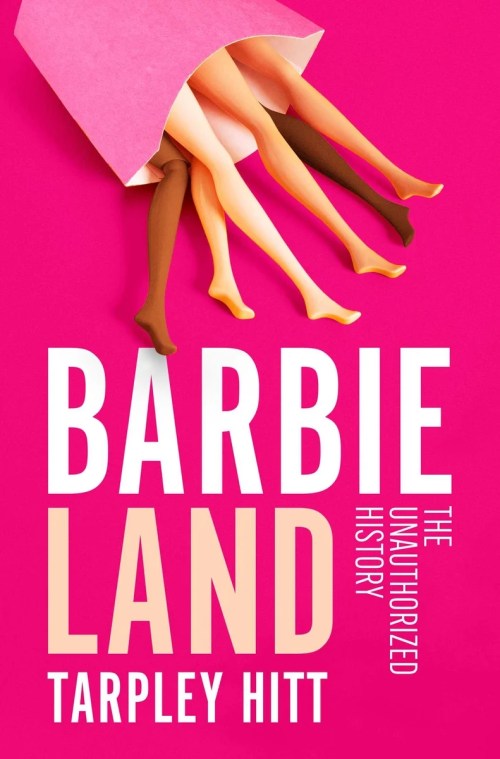

Nonfiction

Barbieland

By Tarpley Hitt

Atria/One Signal Publishers

Published December 2, 2025