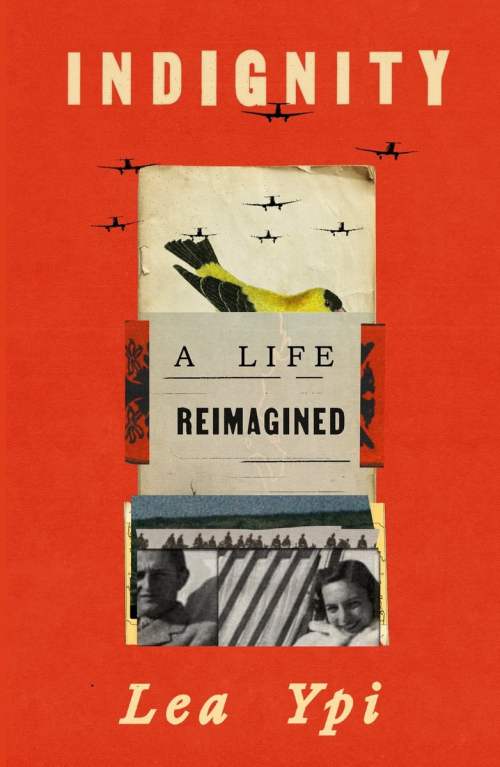

From time to time, every social media user feels a twinge of unease at the distance between their true self and their online avatar. This haunting disjuncture is the starting point for Lea Ypi’s family history, Indignity: A Life Reimagined. Ypi’s own experience is narrated in the first person through a prologue, a coda, and an array of interjections. But the bulk of the story retells the life of her grandmother: Leman Ypi.

Leman was born in what is now Thessaloniki, Greece, but was at the time a multicultural outpost of the decaying Ottoman Empire. Her life spanned two world wars, the collapse of empires, and rise and fall of totalitarianism. It would be difficult to track anyone’s story across such a variegated historical landscape. But Leman’s granddaughter Lea, a political philosopher at the London School of Economics, is well-placed to try. To the philosopher’s preoccupation with weighty existential themes Ypi adds the insights of a novelist: the narrative of Leman’s life is textured, emotionally intimate, and, especially in the first half, related with a dry wit.

The balance between philosophical musing and storytelling is a hard one to strike, as anyone who has read (or attempted to read) Thus Spoke Zarathustra knows. For the most part, Ypi manages the tonal shift well. She uses the concept of dignity to illuminate the gulf between identity and representation. It is a separation that precedes the social media age, a separation that assumed a particularly grotesque form in totalitarian states where intelligence services cobbled together elaborate dossiers on anyone suspected of party disloyalty.

Ypi relies on these scattered reports from the Albanian police, the dreaded Sigurimi, alongside her own family lore to piece together the life of her grandmother. As a rebellious youth, Leman made the fateful decision to leave Greece and move to Tirana, Albania. She took a job, embraced and discarded political movements, and fell in love, all in the shadow of Albania’s short-lived independence, fascist occupation, and subsequent communist regime. It was this last government, the most durable and repressive brand of communism in Eastern Europe, whose Sigurimi secret police tailed Leman, interviewed her friends and colleagues, imprisoned her husband, and confiscated her assets.

Indignity, part novel, part narrative nonfiction, oscillates between multiple versions of Leman. First, there is the doting grandmother that Ypi remembers, the version that readers met in Ypi’s previous non-academic work, the memoir Free: Coming of Age at the End of History. Then there is the picture of Leman cobbled together by fragments of Sigurimi intelligence, a potential class-traitor married to the son of the former Prime Minister of Albania. Finally, there is the Leman that galvanized the younger Ypi to write Indignity: a young woman posing in a photo taken in 1941, honeymooning in the Italian Alps high above war-torn Europe. That photo would resurface as a wave of Sigurimi files were declassified and circulate across social media in Albania before inspiring Ypi to undertake the research that led to Indignity.

How to reconcile these Lemans? For a professional philosopher, Ypi is remarkably well suited for the novelistic craft. She weds the emotional insights afforded by fiction to the philosopher’s understanding of concepts: dignity in her grandmother’s story becomes a polysemic thing, a characteristic that changes depending on its possessor but that remains integral to each character’s identity. If dignity is difficult to pin down, perhaps it can be defined by reference to its titular opposite. Indignity opens with an epigraph from Kant: “everything has either a price or dignity.” This would suggest that dignity is a remainder, a core trait that lingers when layers of indignity have been peeled away. To recover Leman’s dignity, to wrench her grandmother’s identity away from the representations made by Sigurimi and social media commentary on an old photo, Ypi turns to that peculiar fusion of the real and the imagined: historical fiction.

Arriving at a time when the concept of universal human dignity is being challenged, when human rights institutions and norms are buckling under the weight of a nationalist, populist onslaught, Indignity offers poignant historical lessons. In one memorable scene, Ypi visits Thessaloniki’s Jewish cemetery, whose remnants are a memorial to a once thriving community extinguished during the Nazi occupation of Greece. The community has vanished but a small memorial to its cemetery remains. Despite its modesty, however, the memorial is frequented by local neo-Nazis. The scene is instructive not just for its depiction of the return of a ghost Europe thought it had long banished, but because it evokes the politics of memory. If memory serves as the battlefield of today’s political contests, then recourse to brute facts can only go so far. History alone cannot settle political debates, just as it cannot answer the question of who the real Leman Ypi was. The archives are incomplete; most of the people that knew her have passed. At best we have fragments.

Indignity’s coda makes clear, in a somewhat didactic fashion, what the fictional narrative has already suggested: to know a person, alive or dead, is to imagine them. And imagining the past, as Walter Benjamin knew, is no simple thing. It is a profoundly political act, the tool each generation possesses for refashioning the present, as he makes clear in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History”: “The past carries with it a temporal index by which it is referred to redemption. . . . Like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak Messianic power, a power to which the past has a claim.” In this way, Ypi has set out to redeem her grandmother and, in the process, cross the illusory chasm between Leman’s time and our own.

NONFICTION

Indignity: A Life Reimagined

By Lea Ypi

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published November 4, 2025

Jake is a PhD candidate in Political Science at Northwestern University and holds a JD from Boston University School of Law. He has an abiding, if only occasionally requited, love of hounds and Arsenal FC.