Human history is full of popular ideas that have gone on to be debunked. The earth used to be the center of the universe. Doctors once smoked in the exam room and didn’t bother washing their hands. But of all laughable ideologies from the not-so-distant past, the most notorious could be the so-called science of eugenics.

The odious study of “racial types” has been washed up for almost a century, but a new historical analysis by Michael Rossi traces the rise and fall of eugenics in America from a wholly unexpected vantage point—the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Rossi endeavors to splash cold water on the subject by exploring the strange fascination that influential eugenicists developed with Hawaii, specifically one of the Aloha State’s most famous families, the Kahanamokus.

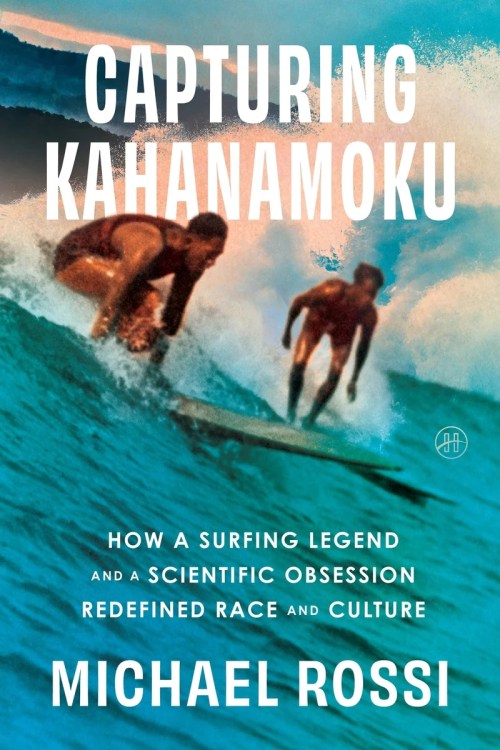

Capturing Kahanamoku: How A Surfing Legend and a Scientific Obsession Redefined Race and Culture is well researched, engrossing, at times out of touch, and entirely oddball in its approach—namely in the parallel that it draws between the growth of eugenics in the American zeitgeist and the love affair that white, mainland Americans developed with Hawaii. Leading eugenicists of the time harbored an unhealthy, paternalistic obsession with Polynesian people and their cultures, and Rossi is dutiful in sharing evidence for this—like the cringeworthy notes and letters of visiting scientists from New York who spent countless hours measuring and documenting the minute dimensions of unsuspecting residents of Honolulu at the time. But Rossi’s argument hinges on eugenicists’ obsession with the legendary athlete and unofficial Hawaiian ambassador to the world, Duke Kahanamoku, and his lesser known but highly accomplished brother David. That argument stands somewhat unsteadily upright—it is mostly sound in the broad strokes but wobbles a bit when subjected to scrutiny.

Rossi’s practiced, expository style unearths the roots of eugenics in the United States, and while this history was morbidly interesting, I found the biographical passages about Duke to be the most engaging and enjoyable. Duke Kahanamoku was larger than life—a champion Olympic swimmer and world record holder, surfing pioneer, entrepreneur, Hollywood movie star, community leader, and successful politician, among other things. With the passage of time, Duke has gained recognition beyond the shores of Waikiki and today deserves to be ranked among the most enduring athletic icons of the twentieth century, on par with Paul Robeson or Muhammad Ali. I was charmed, as Duke’s generation was, by his origins as a scrappy beach urchin who impressed tourists by diving for coins off the pier in Honolulu. Rossi imparts many such picaresque anecdotes of Duke and his milieu fluently, building up a narrative momentum that helped carry me through the drier chapters consisting of correspondence between the country’s foremost eugenicists.

“It wasn’t uncommon, for instance, to see Duke or David roll forward into a handstand on the noses of their boards as they rocketed shoreward. After a moment, they’d calmly cartwheel back into standing position as sea spray shot around them. Other times, riders demonstrated their strength by paddling out with a child or a woman on their board, then hoisting them aloft on their shoulders when they caught a wave.”

On a parallel narrative track, the book follows a leader of the eugenics movement and head of the American Museum of Natural History, Henry Fairfield Osborn, whose great influence within scientific circles in the early twentieth century was nearly matched by his stature in the public imagination. Rossi makes a suitable villain out of Osborn—a joyless and stern scholar, a nephew of J.P. Morgan hailing from a fabulously wealthy family, educated at Princeton, who uses his powerful position at the American Museum as a bully pulpit to promote the relatively new field of eugenics as a panacea for all the ills of western civilization, as he sees them. In his many speeches, letters, and public comments, Osborn harangues against the “enervating” consequences of “mixing blood” and extolls the virtues of the “Anglo-Saxon race.”

Osborn arranges for a junior scientist from the museum, Louis Sullivan, to travel to Hawaii and take the measurements of locals there—a practice known as anthropometry—in advance of the second world conference on eugenics. As one might imagine, the project is awkward for everyone involved. But it only gets more embarrassing and disturbing when the eugenicists from the museum seize a rare opportunity to measure a local luminary, David Kahanamoku. David’s brother Duke is more famous and a more coveted subject for scientific study, but Osborn and company take what they can get. They go on to create a full-body plaster cast of David through a physically torturous process that proves so traumatic, David cuts off access to Duke and refuses to submit to any other bizarre rituals in the name of pseudoscience.

The cast of David Kahanamoku is the critical moment that gives the book its title. It’s also the only direct interaction between America’s silliest scientific discipline and modern Hawaii’s most famous family. While interesting, I found this moment a little “enervating” myself, a little shrug-worthy, and perhaps a bit underwhelming, since Rossi’s title derives entirely from this fleeting and uncomfortable clash between two different worlds. I wished for something more substantial, and ultimately, Rossi’s dual narratives felt a bit isolated from one another.

Rossi can get bogged down in the niceties of conversation amongst eugenicists—the “he said, she said” of the time—which may be his way of staying true to the historical record, but such minutia was tangential to his argument and a bit macabre, simply due to the sheer amount of attention paid to it. In the end, it doesn’t matter if one eugenicist is a socialist and another is for women’s suffrage. They are both on the wrong side of history and the scientific method. All this became clear with the rise of Hitler in the 1930s, when America’s most celebrated pseudoscience began to rapidly lose its luster.

Despite its eccentricities, Capturing Kahanamoku deserves applause for wrangling a sticky subject and holding it up to the light. I was reminded of other acclaimed “history of science” volumes with well-researched and engrossing narratives, like The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot or The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee.

We can now breathe a sigh of relief, knowing that eugenics has been relegated to the trash heap of history. If there is a victor in the contest described by Rossi, it is Duke Kahanamoku, the valorized surfer and athlete whose physical body may be long gone, but whose larger-than-life statue still welcomes visitors to Waikiki beach today, bronze arms extended and bedecked with fresh leis.

Nonfiction

Capturing Kahanamoku

By Michael Rossi

HarperOne

Published October 21, 2025

Max Gray is a writer and artist of many stripes. His essays and criticism have appeared in the Chicago Review of Books and The Rumpus. His science fiction story "The Simulation" appeared in Amazing Stories' Best of 2024 anthology. You can hear him perform and learn more about him at maxwgray.wixsite.com/max-gray

This seems to me the most unserious book review I have ever seen. I have not ready Rossi’s book yet–which is why I was looking at reviews–but I can distinctly tell that Rossi’s objective and argument is different from what was discerned (or failed to be identified) here. Merely judging by the title of Rossi’s book, it is clearly about the lasting impacts of eugenics on our perception and aesthetic preferences, rather than Gray’s impressions at the level of “isn’t this laughable now” and “learning about surfer dudes is quaint” type of statement. In fact, it might be quite interesting to learn why a socialist would choose eugenics as their trade. “It does not matter” to Max Gray here, but nuance is all we have in any worthwhile inquiry. Anyway, Rossi recently wrote a short article on the same subject for LARB, so I recommend that to anyone who is looking to find out more about the content of his book like I was. It is certainly more informative that this review here. Honestly, I was questioning whether this was written by a teenage boy for a second. Turns out that is Gray’s audience. But why would he review this book then?