From the first page of Brandon Hobson’s The Devil is a Southpaw, readers are warned they may be entering a false narrative. The book opens with a foreword that casts doubt on its own reliability, suggesting that what follows is both a memoir and an invention of a “possibly unreliable account” of a childhood. That uncertainty becomes the novel’s engine: is this subject Matthew’s story, narrator Milton’s, or both? Is it a dream, a confession, or a hallucination stitched together by fragments of memory and art? Hobson blurs the line between truth and fiction to ask a deeper question: how do we make sense of violence, loss, and survival when reality itself can’t be trusted?

At its center, The Devil is a Southpaw follows two boys whose lives intertwine inside a violent juvenile detention facility: Matthew Echota, an eccentric and brilliant Cherokee artist haunted by visions, and Milton Muleborn, the narrator whose perspective slips in and out of certainty. We learn the facility itself was shuttered after widespread abuse became a crucible where survival depended on notebooks, drawings, and secret acts of imagination.

The book explores Matthew’s unusual abilities; he predicts deaths and disasters before they happen and remains calm in solitary confinement by sneaking books and hiding them in the walls. His seeming relaxation and meditative demeanor inspire both jealousy and awe among his fellow inmates. Rumors swirl about Matthew’s past and his famous father, a Cincinnati Reds player who fell from grace. Meanwhile, Milton orbits Matthew while battling his own demons, an abusive father, a strained romance with a girl named Cassie, and an obsession with stories that blur into reality.

Letters from the afterlife, fake movie synopses starring John Wayne, surreal encounters with Frida Kahlo, and a spectral girl named Nora all complicate the question of what is real and whether Matthew and Milton are two boys, or just one fractured self. Hobson’s most striking choice in The Devil is a Southpaw is the density of its style. The novel is saturated with sensory descriptions, woods alive with mythic “little people,” meals that punctuate brutal labor, and prison bedrooms charged with dread. This thick imagery can be intoxicating, creating a dreamlike momentum, but it also risks overwhelming clarity. Readers may find themselves caught, like the characters, between a vivid hallucination and a grounded account. Formally, Hobson refuses convention. Photographs and sketches appear between chapters, echoing the notebooks Matthew uses to stave off madness. Poems interrupt the narrative, while letters from the afterlife destabilize the passage of time. Even the title doubles itself, referring both to a superstition passed down by Matthew’s father and to a fake movie whose synopsis heavily echoes the boy’s story.

Characterization, too, is deliberately unstable. Matthew emerges as both prophet and outcast, a boy whose predictions of death blur the line between mysticism and mental illness. Milton’s narration is equally unreliable, sometimes shading into Matthew’s perspective until the two seem inseparable. Their shared obsession with art, poems, movies, and drawings becomes a lifeline, a way to resist a system intent on erasing individuality. At the same time, Hobson’s layering of surreal spaces and ghostly visitations underscores how trauma can dissolve boundaries between imagination and memory. Hobson situates The Devil is a Southpaw within a lineage of American storytelling that reshapes memory and art.

Ghosts, artists, and cinematic references crowd the narrative, situating the boy’s suffering alongside a broader meditation on art’s power to both distort and preserve. The novel also speaks to ongoing conversations about incarceration. The juvenile detention center, modeled after real facilities that closed in disgrace, becomes a stand-in for the systems that label children irredeemable. By filling this space with poetry, drawings, and film allusions, Hobson asks what possibilities remain for creativity in a world determined to stamp it out. Stylistically, the book belongs with writers who bend reality into myth, such as Shirley Jackson’s haunted suburbs, Don DeLillo’s meditations on violence, or even Roberto Bolaño’s obsessive narrators. Yet Hobson’s voice is distinct in its insistence that stories themselves, whether unreliable, fragmented, or overly fictional, are what allow his characters to survive. The novel leaves us questioning whether truth matters less than the art that shapes it. In the end, The Devil is a Southpaw resists the neatness of resolution. By entwining Matthew and Milton, blending hallucination with memory, and layering fact with invention, Hobson makes disorientation the point. The novel is less about what “really” happened than about how violence and art echo through fractured lives. For readers, that instability can be frustrating, but it is also what gives the book its driving force. Hobson leaves us with a paradox; the most unreliable accounts may be the truest ones, the stories we tell, half myth, half memory, are often the only means of survival.

FICTION

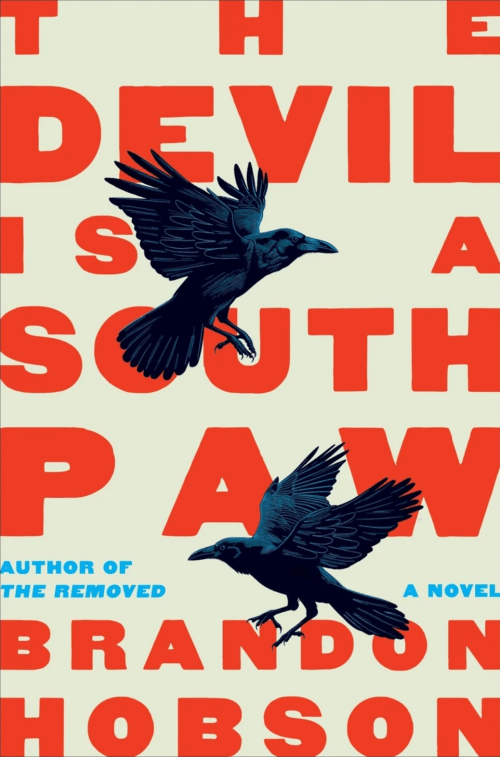

The Devil is a Southpaw

By Brandon Hobson

Ecco

Published October 28, 2025

Olivia Zimberoff recently completed the Columbia Publishing Course in Oxford, England, after earning her BA in Creative Writing from Lawrence University. She has studied improv and writing at the Second City and volunteers with Open Books, a nonprofit promoting literacy in Chicago. An avid reader who loves discussing books and pop culture, she is now pursuing a career in publishing.