It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a cathedral in possession of a good writer must be in want of a . . . statue?

This year marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth (December 16, 1775). In October, a Jane Austen sculpture will be unveiled at Winchester Cathedral where the beloved English author is buried. Festivals, multiday tours, BBC programs, and museum exhibitions have been scheduled all this calendar year in the UK. The rest of the Anglophone world is not to be outdone. From Springfield, Missouri to Brisbane, Australia, Janeites can enjoy screenings of Jane Austen film adaptations and attend balls requiring Regency attire. Not everyone is happy with the fanfare. No less an esteemed figure than the vice chairwoman of the Jane Austen Society, Elizabeth Proudman, has proclaimed in reference to the Winchester Cathedral statue: “I don’t think the Inner Close is the place to attract a lot of lovely American tourists to come and have a selfie with Jane Austen.” Austen herself could not have dreamt up a better chairwoman’s name or a more graciously condescending way to address the frenzy for someone Jane Austen scholar Devoney Looser describes as “a genius novelist and a literary icon. Mic drop.”

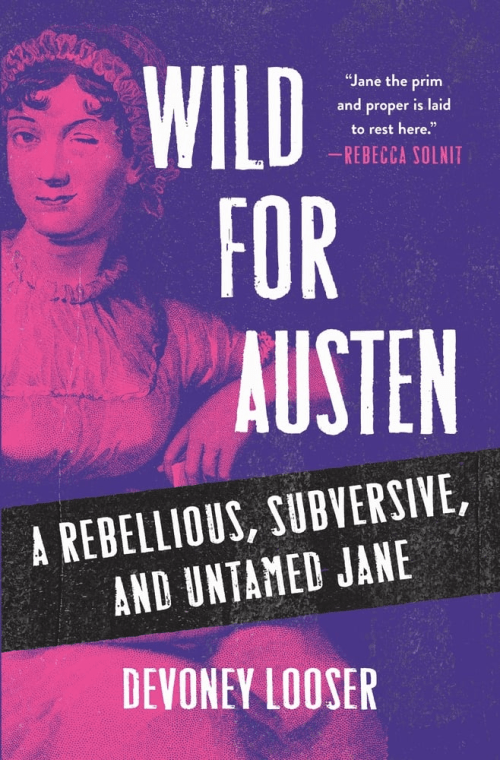

If an empty purse or fear of Proudman’s disdain prevents you from making a pilgrimage to Austen-related British sites, consider reading Looser’s Wild for Austen: A Rebellious, Subversive, and Untamed Jane. Looser, an Arizona State University Regents Professor of English and roller derby player, lives up to her name by taking readers for a walk on Austen’s wild side. Serious scholarship has rarely been so charming, entertaining, and revelatory all at once.

Looser’s objective is to set the record straight on Jane Austen (1775-1817), who has long been inaccurately characterized as having led the quiet, sheltered life of a spinster. In demonstrating Austen’s subversiveness, Looser provides close readings of the author’s six novels as well as lesser-known works. These include Austen’s Juvenilia, a collection of stories, plays, letters, and histories, which were written when the author was between eleven and seventeen years old. Juvenilia reflects early literary sophistication with works that are parodic, irreverent, and darkly comic.

Part II discusses Austen’s family and friends, providing new information about their hijinks, involvement with the abolitionist movement, and wildly different stances on women’s suffrage. Here, Looser describes the colorful people in Austen’s social set. These include an (alleged) shoplifting aunt and a family friend who may have been an international spy. We also learn there were other women writers on the Leigh side of Austen’s extended family. Among the Leigh collected works housed at the Morgan Library in New York is a certain English poem translated into Latin: “A Match at Farting,” about a woman who resourcefully uses her wind to ignite and extinguish candles.

Part III looks at Jane Austen’s lasting cultural impact. While interesting and informative, this section is not as compelling as the first two-thirds of the book, despite including a chapter on Jane Austen erotica. One suspects the uncomfortable stickiness in addressing difficult topics such as cultural colonization and its enduring impact can be difficult to discuss in a book so deliciously breathless and gossipy. Looser acknowledges the harm that can result from privileging English (read: white) literature, yet she seems reluctant to be her derby team’s jammer and risk getting tossed in the penalty box for rough play. Malawian poet Felix Mnthali’s “The Stranglehold of English Lit” (1961) receives a scant two pages of her incisive attention, leaving one longing for a more in-depth discussion about what it means to elevate English literature in a colonial and postcolonial context. To be fair, Looser later notes that she previously addressed the poem’s message in a 1995 publication. Yet even if we grant that Wild for Austen does not need to revisit this particular poem, Austen as an icon for a limiting notion of “Britishness” is worth exploring further. In Wild’s final pages, Looser observes that “Austen is being embraced today by the alt-right.” One wishes the author had explored the why and how of this further.

Given the increase in white supremacist violence in the United States and beyond, Looser’s chapter on almost-made twentieth-century film adaptations of Pride and Prejudice strikes this reader as less relevant for contemporary readers than one addressing, say, Austen’s legacy and influence on the popular Netflix show, Bridgerton. For those unfamiliar, Bridgerton is a costume romance television series created by Shondaland, a production company helmed by Hollywood writer and producer Shonda Rhimes. The series lit the quarantined world on fire when it debuted in 2020. Set in Regency England, Bridgerton shares themes in common with Austen novels such as flirtations, courtships, and the resort town of Bath. It also includes significant departures such as steamy sex scenes and a racially diverse cast. While many have praised the show for its representation of people of color in prominent roles (Queen Charlotte!), others have been critical about there being no mention of the historical fact that many of the richest Brits gained their wealth via the transatlantic slave trade and Caribbean sugar plantations in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some have explained this detail away by noting that Bridgerton is a fantasy. Looser’s perspective on a prominent and contentious pop culture heir to Jane Austen’s works would have been a welcome addition to a consideration of the author’s enduring impact. This omission notwithstanding, Wild for Austen is a must-read for anyone who can’t get enough of Jane Austen.

NONFICTION

Wild for Austen

By Devoney Looser

St. Martin’s Press

Published September 2, 2025

Lori Hall-Araujo is a communication scholar and visual artist.