Most American road trip books begin with a brief explanation of the author’s motive for hitting the road. In Travels with Charly in Search of America (1962), John Steinbeck describes his desire to reacquaint himself with a country that he’d fallen out of touch with. In The Great American Bus Ride (1993), expat Irma Kurtz sets out to discover her “unknown homeland” for the first time. William Least Heat-Moon begins Blue Highways (1982) by recounting the moment when the idea for his three-month cross-country road trip first arose. He had lost his job as an English teacher. He had just learned that his estranged wife was seeing someone new. Suddenly, it occurred to him that “a man who couldn’t make things go right could at least go. […] It was a question of dignity.”

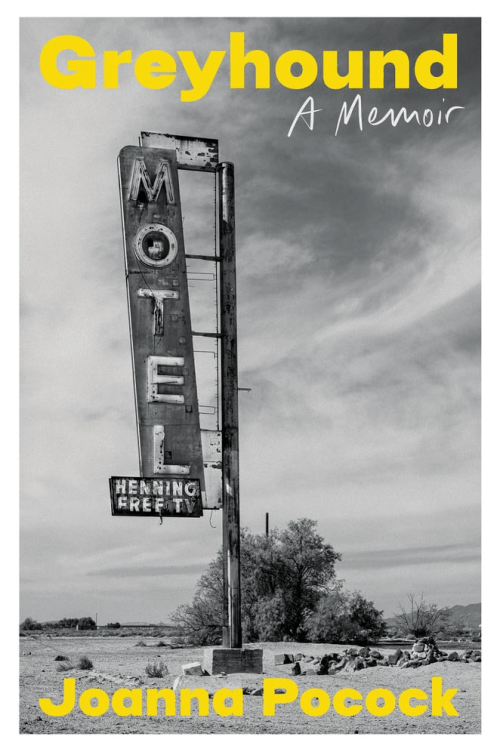

In the opening pages of her memoir Greyhound, Joanna Pocock offers a dual motive for her travels: to take stock of America and to take stock of herself. Unlike most road trip books, Greyhound is a comparative account of two journeys, both by Greyhound bus from Detroit to LA, both lasting roughly three weeks in early spring. Pocock undertook the first journey in 2006 at a low point in her life—her sister had recently died, and she had just suffered her third miscarriage. In 2023, she recreated the journey, attempting to revisit as many of the cities, highways, and motels as possible from her earlier trip. In Greyhound, she records the way these places have changed, reflects on how her identity has developed, and creates a fascinating exploration of the meaning of “place” in the process.

Pocock’s evaluations of changes to the cities and locations she’d visited in 2006 are almost uniformly negative. In Detroit, she sees overly rapid renewal and gentrification leaving a significant portion of the city’s population behind. In St. Louis she sees the opposite. Bars and music venues that she visited in 2006 are now closed. The riverfront area is abandoned. These observations seem to put cities in a no-win situation, where both new investment and its absence create problems. But balancing economic vitality with inclusion is a real and ongoing challenge for post-industrial cities, so Pocock’s observations ultimately serve as more of a helpful reminder than a complaint.

Her experience with Greyhound is similarly bleak, as she sees more desperation in her fellow passengers, experiences less camaraderie, and consistently feels depressed or endangered by the conditions at Greyhound stops: for example when she’s forced to wait for hours by the side of a six-lane road in Phoenix without access to water, shelter, or a bathroom. As with her response to urban development, these observations register the feeling of living in a world that prioritizes profit over people, but in this case, Pocock directly names the systemic forces responsible for producing these feelings. As she notes, and as several news sources have reported over the last few years, Greyhound has recently sold its bus stations in several major cities to private developers, depriving those cities of important public spaces and forcing bus passengers (roughly 75% of whom earn less than $40,000 annually) into inconvenient or dangerous circumstances like the ones Pocock encountered. After a particularly difficult wait in Columbus, Ohio, she writes that the phrase “Something in the US has broken” echoed in her mind, but maybe it’s more accurate (and horrifying) to think that things are working exactly as planned as far as corporate profits are concerned.

As Greyhound progresses, Pocock begins to reflect more directly on her involvement in her observations. In Tulsa, for example, she wonders whether she failed to encounter the same sorts of colorful characters she once had because they were all absorbed in their phones, or because as an older woman, she no longer attracts the same sort of attention from men. She leaves this question unanswered, much like the question of how she feels about this change. She’s relieved that she can travel without being constantly interrupted but also feels sad “leaving something precious behind that [she] would never have again.” Towards the end of the book, she notes that she had almost no substantive interactions with other people on her trip, concluding that the 2023 version of her journey held less “tenderness” for her than the earlier one.

The second half of Greyhound also returns Pocock to the American West, a landscape she loves deeply and describes with nearly reverential language. She looks forward to approaching Amarillo because “the earth would be turning ochre and red, the light would travel for miles, […] draping everything with golden light.” The desert outside Albuquerque is “perfect.” Her writing at these moments recalls her 2019 book, Surrender: The Call of the American West, in which she detailed her experience living in Montana with her family for two years, struggling to find a way of life that existed in harmony with Earth rather than imposing on it. It also recalls moments in both Surrender and Greyhound when Pocock discusses the lack of connection she feels to the suburb of Ottawa in which she was raised. In both books, Pocock characterizes her interest in the American West as an attempt to find a more authentic relationship to Earth than the one she recalls in her hometown, which, like so many urban and suburban spaces, was based on “extraction and exploitation.”

There are times in Greyhound, for example when Pocock visits an urban farm in Detroit, when it seems like she might be able to find this sense of rootedness, even in urban spaces. But there are other times when it seems like the basic operations of human consciousness preclude the sort of belonging she desires. Partway through Greyhound, she recalls a scene from Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac in which Leopold marvels at cranes and their prehistoric fossil record. She compares the birds’ histories to the “sodden pages of [her] own history,” seemingly referring to her suburban childhood. But then she widens the scope to humanity as a whole, writing that “these ancient creatures know precisely in the core of their beings the shape and texture, the give-and-take of a patch of Earth, and how to function within its cycles in a way that is alien to us.” From this vantage point, human experience is alienated by definition. To be human is to be impure.

But this isn’t where Greyhound stops. Instead, it uses its ecological consciousness to direct readers’ attentions to the natural world, thoughtfully probes the boundaries of its own awareness, and honestly struggles to achieve a comfortable sense of place. Much like Surrender, it ends with a pledge to continue cultivating a sense of belonging and a feeling that, for Joanna Pocock, “home” may involve a set of ongoing practices rather than something she achieves once and for all.

MEMOIR

Greyhound

By Joanna Pocock

Soft Skull

Published August 12, 2025

I teach English composition and literature at the University of Pittsburgh. I also review books for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Boston Globe, among others.