If you live in roughly one place all your life, the physical idea of home may not be that complicated; if you move a lot, or are even forced to leave your country, searching for belonging may become a mainstay. Where can you locate your memories? Where can you count on finding the people you love? The political exploitation of land, of people, only adds to the burden of carrying the memories of those lost places.

As Palestinian-American Hala Alyan writes in her new memoir, the Levant of her heritage “came to mean perpetual departure, a border that always changed, belonging as a tenuous thing.” A place you could never really leave, nor return to.

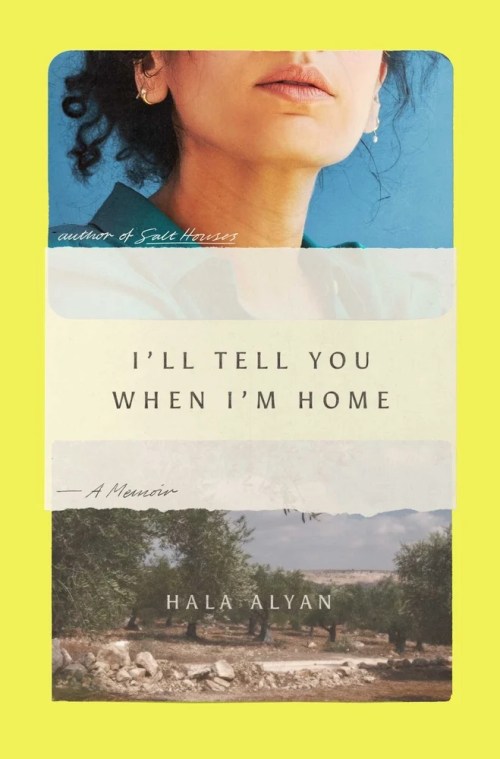

Alyan, a poet, novelist, and clinical psychologist, returns with her first work of nonfiction, I’ll Tell You When I’m Home. The book is framed around the gestation of her child, each month a guidepost of reckoning with the past, sharing family and personal history as a ritual or an offering. A surrogate is carrying the baby after Alyan suffered through years of pregnancy losses.

But much more than a work about pregnancy and childbirth, I’ll Tell You When I’m Home at once grieves all Alyan has lost from her upbringing while nurturing a life in Brooklyn with her husband after years of coping with alcoholism and moving from country to country.

As always, Alyan’s poetic prose encapsulates miles in each sentence and paragraph; joyfully, revisiting a passage is another chance at uncovering a new gift. Her nonfiction narrative voice allows the poet in her to shine, especially as each chapter is told in a series of short glimpses weaving together past and present, the old and the new Hala. Along the way, it seems, she discovers her old and new selves comprise the same tangible person—one she learns to love and trust enough to be a mother.

Alyan’s childhood spanned Kuwait, Texas, Oklahoma, Maine, the United Arab Emirates, and Lebanon. Her book questions what the Levant, what being Levantine, really means:

“The Levant wasn’t just a place; it was also a people, and a certain kind of people at that. A fickle kind of people. An in-between kind of people… Everything, eventually, came west. To be Levantine was to be stilted, half-colonized, not quite there.”

Perhaps that “not quite there” is key to other aspects of Alyan’s identity that play out as she enters adulthood. She starts drinking in earnest in college, in Beirut, while her family moves on to Qatar, leaving her with more freedom than she’s ever had.

She writes that “a blackout is the most spectacular magic trick of all. You erase yourself without anyone knowing it… I never knew who took over when I blacked out. Maybe it was a stranger. Or maybe it was me, the actual me, the truest one.”

Like drinking, erasing yourself can also be an addiction. She describes both as being powerful things she learned to harness.

She iterates a fear of losing her past throughout the memoir, trying to make sense of a home she can present to her daughter. She’s lost relatives without the chance to say goodbye, and Middle Eastern cities where her family lived have fallen. She is failing to save these things, she feels, while simultaneously failing to sustain a pregnancy. In a striking line she says, “I have glimpsed the terror that accompanies love like a bodyguard. My pregnancies have taught me caution, a moratorium on daydreams.”

She could control her body in so many ways, drinking until she disappeared and getting thin from not eating. “But I couldn’t make it stay pregnant,” she writes. “I couldn’t make it make a life.” Now, she worries that her daughter will be left with only Alyan’s stories of her family and of their cities.

Could the salve be to continue and participate in those stories? Logging memories, sharing, connecting, and retelling; being unashamed of a family’s past and her own. She starts recording herself telling these stories so the surrogate can play them for the unborn baby. In one, she tells her, “These stories are yours in a way too, have made you, because they’ve happened to those that made you.”

Even the notion of a story can be used to get through a tragedy or cope with pain. Sitting in the ER after another pregnancy loss, Alyan describes playing a game to get through it:

“When I say played a game with myself, I mean the story is what saved me. Knowing the story was coming. Knowing someday I would tell it. The story itself reminded me that I wouldn’t always be in that room, in that light, staring at a drying smudge of blood.”

Putting distance between what you’re experiencing and the story of it creates a barrier. It creates space that can lead to acceptance and resilience. She says, “In narrative therapy, this is called externalization: the mere fact of the story means you are outside the story.”

With I’ll Tell You When I’m Home, Alyan has created a record, a story to communicate with those departed and those new to life. In the process, her work is an antidote for others searching for a home they never asked to lose.

“Every story is a retelling of another story,” Alyan writes. That fact is a comfort; recognition that none of us is ever truly alone in adversity.

NONFICTION

I’ll Tell You When I’m Home

by Hala Alyan

Avid Reader Press

Published June 3, 2025

Meredith Boe is a Pushcart Prize–nominated writer, editor, and poet. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Passengers Journal, Newfound, Another Chicago Magazine, Chicago Reader, Mud Season Review, After Hours, and elsewhere, and her chapbook What City won the 2018 Debut Series Chapbook Contest from Paper Nautilus.