The late literary critic Harold Bloom remarked that compared to any century prior, many of the greatest writers of the twentieth century and after were atheist or agnostic in bent. One can say, in turn, that this bent is a general trend of Western society as a whole, not a trait particular to writers. The causes are many; perhaps the most notable cause was a loss of faith in rationalism, a loss brought about through cultural forces including the back-to-back World Wars. Despite our Enlightenment ideals, despite our science, and despite our churches and academies, those atrocious conflicts broke out and ran unhindered for years. To put it one way, can we believe in a rational, loving, virtuous core to the universe (a possible definition of God) in a world where our personal and societal efforts collapsed in such devastating fashion?

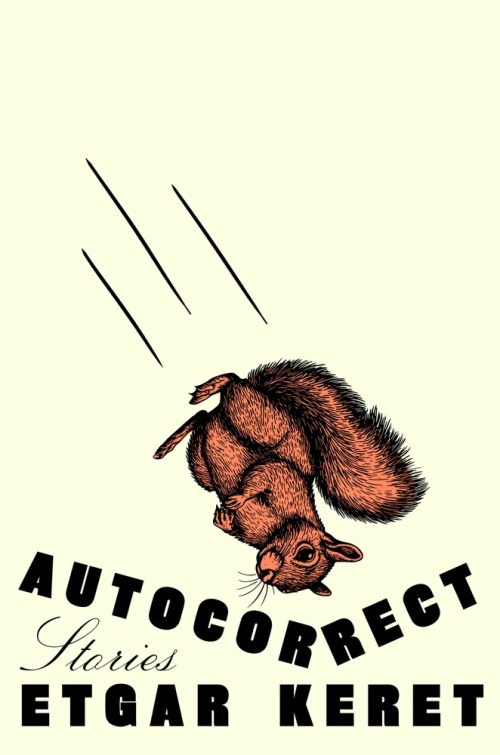

These thoughts stirred while reading Etgar Keret’s latest collection of short stories, Autocorrect. It is true that many of the stories are funny and thought-provoking. They’re what you’d call dark comedy. But in Autocorrect, there’s something further. Even in works of dark comedy, we often get a sense that a system of justice, sometimes called karma, exists in the world. A person behaves in an evil, cruel, or merely unpleasant way, and something bad happens to them in turn. One can either believe this is an aspect of wish fulfillment in art, or an intrinsic property to the real moral, spiritual, or even physical universe — the reader can decide for themselves. Autocorrect is willing to live outside of this framework.

Etgar Keret is an Israeli writer in literature and film. His works have been translated in over four dozen languages, his writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Le Monde, and he has won several awards in film. He teaches creative writing at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He runs a popular newsletter, Alphabet Soup, on Substack.

Compared to Keret’s previous work, such as the short story collection The Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God & Other Stories, the tales here are more subtle and swift in execution. For instance, Bus Driver contained a lengthy story exploring an afterlife for those who committed suicide. Characters debate the mechanics of the world, and some mysteries are solved while others are left unresolved. Autocorrect’s story exploring an afterlife, “Present Perfect”, depicts the mysterious circumstances of a waiting line for the dead. By the end, almost nothing is resolved. This is not a weakness, but the suggestion of a growing weariness towards metaphysics and theories, and an increasing turn towards human relationships as the fundamentals of reality — regardless of whatever country, planet, or heavenly sphere we find ourselves in.

The themes that continue to stand out in Keret’s work are human relationships, especially those between men and women, and parents and children. The story “Soulo”, about the dissolution of a married couple’s relationship—and the resulting complications when both man and woman hook up with AI companions—is brilliant. The relations between the four characters are funny, insightful, and proceed with astute cause-and-effect. Another story, “Earthquake”, painfully portrays the loss of a potentially great love through the passivity of the male protagonist.

Some stories take on more of a Borgesian feeling, such as “Director’s Cut”, where a filmmaker spends their entire life making a seventy-three-year-long movie. The only survivor of the audience to the film is a baby born during the screening. Other stories feel like meditations akin to the tales of the Hasidim, Jewish mystics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In “Mitzvah” and “Intention”, the protagonists are involved in prayers, followed by enigmatic outcomes. Unlike the Hasidic tales, however, the reader gets the sense that a religious spirit does not really help anything. It was the nearly random sequence of events of “Mitzvah” that led to the blossoming of thoughts contained at the beginning of this article.

In all, Autocorrect is a grab bag of over thirty stories, largely united in feelings of laughter, sadness, and—besides the few fortunate men and women who find love within these narratives—pessimism. The senseless violence and fears of the World Wars are no longer felt by many in the United States, but similar sentiments are common where warfare continues to be a constant.

FICTION

Autocorrect

by Etgar Keret

Riverhead Books

Published May 27th, 2025

Philip Janowski is a fiction writer and essayist living in Chicago. He is president of the Speculative Literature Foundation's Chicago Branch, a member of the Chicago Writers Association's Board of Directors, and a presenter with the late David Farland's international Apex Writers group. He has studied under such accomplished writers as Sequoia Nagamatsu, Martin Shoemaker, and Michael Zadoorian. His work in fiction has been awarded with an Honorable Mention from the Writers of the Future contest, and his major project is the upcoming Dominoes Trilogy. He can be reached by his Instagram account (@spiral_go), or by email at (philip@speculativeliterature.org).