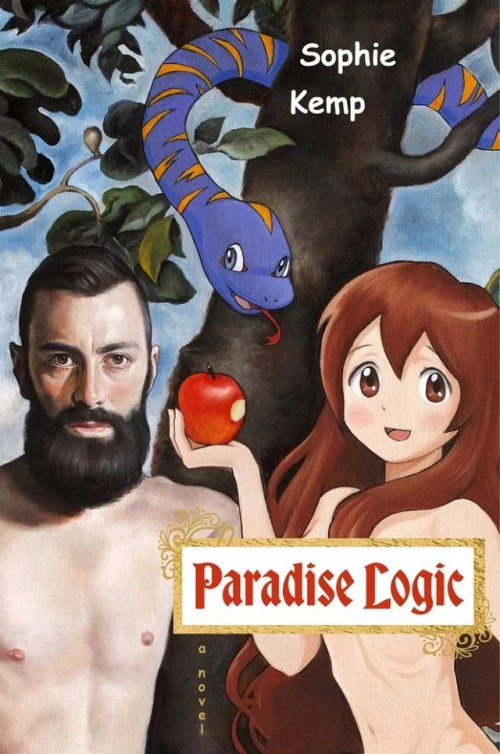

There are troubles in Paradise Logic, Sophie Kemp’s debut novel, but it is finally a triumph. The well-paced story begins 13.8 billion years ago and ends a few years ago. Its human concern begins with a plankton—one “you might even say was in the shape of a girl”—who is to endure or recur as 23-year-old Reality Kahn, a cashier, zine writer, and occasional commercial actress whose quest, cosmically appointed, is to find a boyfriend, and become an exemplary girlfriend. If the cover promises internet literacy or even online immersion, the book that follows draws something of the digital into its pages without surrendering its bookishness, its self-contained life, shaped and voiced by its one author. Kemp takes Kahn, “a kike and a whore” on a romantic adventure, with false starts, delays and divagations. However little has actually happened until “Volume Four”—which one should be advised is not a “volume”—the story has zip, go, and plenty of haha, from the universal beginning to the very particular ending.

Reality’s story is, on one level, mundane, and familiar as the origin of a contemporary novelist. Born in 1996, she grew up four hours north of New York City, and went to Oberlin before moving to Brooklyn, though perhaps less typically, her parents treated her “[l]ike a miracle,” and she majored in theatre. On another level, which could be the sunken level of dreams, her previous incarnations between the plankton and this one spoke to a snake, read some stone tablets hovering over a lake, watched the murder of her father, and came to the city on a boat. (These are her ancestors, maybe, but they are not dead.) Now 23, she has a “low quantitative IQ” and her English is a little odd, not just occasionally redundant but grammatically irregular, sometimes gussied up with French. Paradise Logic is concertedly weird, and this asks of the reader some tolerance, but it is also actually weird, and so demands interest.

Reality is a “punk rock chick” who can drink seven vodkas (which she takes “with eggs”) without getting a hangover, and she is very popular with men. She doesn’t have much money and lives with two college friends, Soo-jin and Lord Byron, who “started doing intercourse” back then, and now, wanting more time as a couple, encourage her in her new plan to find a boyfriend. Reality’s search for that boyfriend is proposed by Emil, her “marijuana merchant” and sex partner, who also wants her to spend less time in his apartment. The boyfriend turns out to be Ariel Koffman, once a piano prodigy and now a doctoral candidate specializing in the Assyrian Empire, who lives in apartment #221 of a building known as Paradise, which is used by him and his buddies as a DIY rock venue. People say he looks like a school shooter, and if this is half a joke, he does treat Reality like a child, and very badly. Worried, she goes on a drug called ZZZZvx ULTRA (XR), patented by a Dr. Zweig Altmann and advertised at the local bodega, in order to “BE THE GIRLFRIEND OF HIS DREAMS.”

One can see the gambit: a confessional, presumed to be autobiographical novel with a farcical mythic framing, and a hyperreal, satirical texture. It is hard to say if Paradise Logic could really have worked any other way, but there are problems in the existing arrangement for all its appeal. While elements of the book design, including the hand-drawn title, map, and illustrations, short sequences of subtitles given their own pages, and smiling emojis used as dinkuses—a word Reality would relish, referring to symbols separating paragraphs—are charming, there are also unpronounceable heart symbols included not just in narration but in dialogue, and the often recurring “ZZZZvx ULTRA (XR),” which is rather unwieldy unlike Kemp’s confected “Demon NRG X-TREME,” an energy drink. This may sound like quibbling, but it is an instance of the uncertainty that besets the book in other areas, and on larger scales. Reality has it that in nice, bourgeois neighborhoods, babies have names like: “Rebecca Stern,” “Bunny Rabbit Jones,” or “Quanta Contra.” It is unclear if we are in a science fiction addled world, or if the addling is only of Reality’s mind, or if this is more like an exaggerated, satirical version of our own. It can be all these, of course, the same generic ambiguity one finds in Pynchon, but the abrupt movement between the three is sometimes a distraction from the giddy experience of the story.

Reality’s dialogue is comically stilted and excessively thorough. She asks for help from her roommates by saying, “I am wondering if either of you have any suggestions as to where I can go to make myself the most eligible bachelorette possible.” Her narration, though, is direct and prompt: it delivers the goods on time, and sometimes early for comic effect. Here is Reality primping before going to the mall to find herself a boyfriend: “The dress I wore was a very large T-shirt. It depicted the Tasmanian Devil, thereby proving I was tough.” She is sometimes slangy, and shrewdly referential, and the contrast between her confiding with us in this way, while sounding like a Martian who learned English with everyone else, is intriguing. But intermittently, the narration goes Martian, and so do the other characters, as if things have been crossed or confused. It’s the same with the trick, which in academia is called defamiliarization, whereby Reality registers things like “a baseball cap with the name of a team from NYC.” This seems important and limited to her character, but then another character speaks the same trick, and later Reality enjoys her “Coca-Cola,” and even repeats the name in relish. (The most generous reader might offer this: the joke is that Paradise Logic is sponsored by Coca-Cola.) There are other inconsistencies. The milieu at Paradise is either never defined or mixed. Kemp seems to be sending them up as trust funded fake bohemians, but later the crowd seems to include someone working in real estate and Reality reports that among their girlfriends “Possible topics of conversation include what country club you all belong to and the best kind of rental helicopters.” A lot of observations from New York life are being worked into a novel that won’t quite fit them. The elitism of those to whom it makes a difference whether you went to Oberlin or Yale can work as a satirical subject in a more earthbound, middlebrow work, but here, sub specie aeternitatis or close to it, it seems a petty concern and somehow below Reality’s notice.

That notice, that vision, is thankfully much bigger than Reality’s biography would suggest, and this mismatch is perhaps the novel’s signal strength as well as its difficulty. The vision is destiny, and however ironically Kemp treats Reality’s progress, however disappointed she is by Ariel, teleology gives the novel a sensation of speed and purpose that can’t be achieved through plotting alone. Reality’s anxiety and desperation can be felt through the page, as she is humbled and exalted at the same time. Like her predecessor, she is mythopoetically importuned by a snake, but she mocks the sinful pride in his speech: “I’m a ssssssnake,” he says in her account. When Reality looks around her, ever afraid, she winces and quips, but she transforms what she’s seen. The novel is vivid, and it is definitely someone else’s life, so its picture of what’s real is different from ours, though just as convincing. Reality Kahn is a tragic loser, as the dust jacket tells us, but her tale has won her enough for consolation, and won us enough for our readerly satisfaction. She is now painfully “experienced,” but there are other realities for her to discover.

FICTION

by Sophie Kemp

Simon & Schuster

Published on March 25, 2025

Kazuo Robinson is a writer based in New York. His reviews have been published by The Adroit Journal, Cleveland Review of Books, The Oxonian Review, and The Millions. He maintains a Substack at kazuorobinson.substack.com where he writes about fiction.