Speculative fiction, a term popularized by Margaret Atwood, has come en vogue as a term for ‘higher’ fantasy and science fiction, or genre fiction with greater aspirations. In science fiction, this usually takes the form of guessing (speculating!) at real scientific developments, and how these developments will shape ethical and practical concerns in our lives. In speculative fantasy works, such as Dennis E. Staples’s Passing Through a Prairie Country, it often means to allegorize concepts that are difficult or even impossible to explore in a narrative built in the world we regularly experience. That is, one formed mostly from sense impressions. The faculty of intuition can see, like a flashlight in the dark, structures that are ordinarily hidden to us. Extensive, painstaking philosophy can attempt to formalize these hidden realities over many labored volumes — and fail anyway. All the while, strange stories survive for thousands of years and speak directly to us. Stories, for instance, warning about ‘ghosts’ that twist human perceptions of the world and influence societies to behave in absurd and dangerous ways.

Passing Through a Prairie Country’s setting is the Hidden Atlantis casino, on the fictional Minnesotan Languille Lake reservation. The casino is presented with a curious ambiguity. On the one hand, characters celebrate it as a place where “numerous friends and cousins […] worked, lived, or played…” and where a declining grandmother, “frail and wheelchair-bound […] saw the rainbow of electric lights on the machines [and] her spirits lifted.” On the other hand, a supernatural spirit called the Sandman haunts the casino halls, dragging people into personally-tailored psychological nightmare worlds and often killing them. Not to mention drug abuse and symptoms of addiction already touching the lives of nearly all the characters, as well as the almost certain loss of money to the slots.

Most chapters are subtitled by their character-of-focus, as well as the date the chapter takes place. Although more than six characters get to have their own chapters, almost half the chapters are focused on protagonist Marion Lafournier. The secondary protagonist, Alana Bullhead, gets about a fifth. The rest of the cast get one or two chapters each, their narratives mostly disconnected from Marion and Alana, creating a sense of anthology. (To help pivot, Marion’s chapters are the only ones presented in first-person, though mysteriously, secondary character Cherie also gets one chapter in the first-person — all the rest are in an observing third-person perspective.) It’s the sort of anthological feeling one expects from novels three times the length of this one, such as David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, or Hanya Yanagahara’s A Little Life. In a shorter novel, one not designed as a collection of short stories, the text can feel crowded, and the purpose of a large cast can be difficult to discern.

The primary narrative follows Marion and Alana in their quest to exorcise the Sandman. Other chapters demonstrate the effects of the Sandman’s “bad medicine” on the assorted cast of characters, including lust-ridden documentarian Gleen Nielan and shattered opioid addict Liam Halestorm.

Although it is not advertised as one, Passing Through a Prairie Country. is a sequel to Staples’s first novel, This Town Sleeps. While Passing Through a Prairie Country.can be read as a stand-alone, certain aspects of the narrative begin to make more sense when taking the previous novel into consideration. In Passing Through a Prairie Country, protagonist Marion can come across as vague, and on first reading, one may wonder why among the crowd he is the stand-out — is he really any more interesting or fitting for a spiritual journey than the rest? The previous novel This Town Sleeps contains Marion’s proper fleshing out and background. The connectivity of these novels may also help explain the exploration of characters of unclear importance to the narrative. One gets the sense that a series is being prepared here, and that several of the characters introduced in Passing Through a Prairie Country are set to have their own novel-length stories.

The novel is presented as a curious puzzle, and it is hard to tell if a solution exists, or if the narrative is meant to simply wash over the reader. The usually precise use of dates assigned to chapters encourages the reader to follow the fictional timeline closely. But these dates do not seem to matter in the long-run, as Marion’s narrative becomes a straightforward hero’s journey, and the other characters mostly disappear into their own diverging ends. There is a surprise to the chronology near the end of the novel, but this surprise could have been presented easily enough without the internal calendar. This technique, as well as a scattering of mysterious phrases and hints (a few addressed in This Town Sleeps, most not) left this reader attempting to keep track of all the puzzle pieces — and by the end, wondering if the mysteries were only intended for loose meditation, or truly meant to be understood.

Sleeping and being awake are themes common to both of Staples’s novels. It is a conception of consciousness found in certain mystic systems: to sleep is confusion, to be deeply associated with false beliefs about the world, and distracted by negative emotions swelled by fear, belief of failure, and potentially nihilism. To be awake is to rise above these dark forces (to use dramatic language), to see the world more lucidly and with a more constant state of self-awareness. The Sandman would put us to sleep, as he does with the characters of Passing Through a Prairie Country, conjuring a mindset where addictions of gambling, drugs, and destructive sex are the best the world has to offer. To sleep too deeply is to “die” — to awareness, and perhaps to life itself. This shadow mythology, presented here by the sinister manidookaazo Sandman, is ultimately to be broken through, to open the eyes wider to light.

FICTION

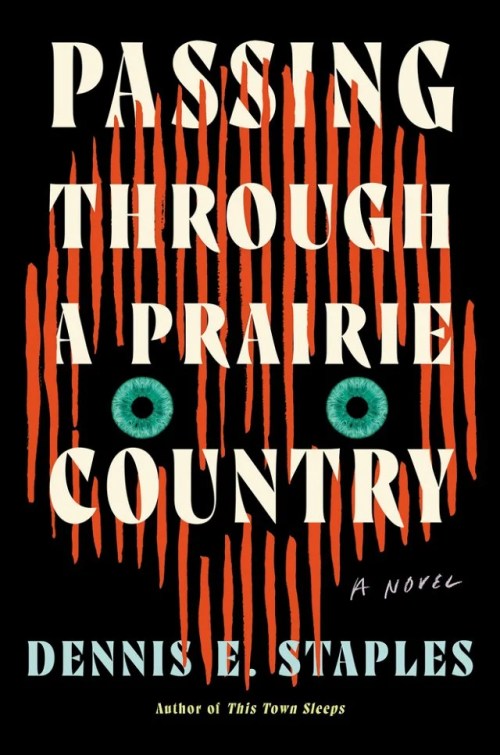

Passing Through a Prairie Country

by Dennis E. Staples

Counterpoint

Published March 18th, 2025

Philip Janowski is a fiction writer and essayist living in Chicago. He is president of the Speculative Literature Foundation's Chicago Branch, a member of the Chicago Writers Association's Board of Directors, and a presenter with the late David Farland's international Apex Writers group. He has studied under such accomplished writers as Sequoia Nagamatsu, Martin Shoemaker, and Michael Zadoorian. His work in fiction has been awarded with an Honorable Mention from the Writers of the Future contest, and his major project is the upcoming Dominoes Trilogy. He can be reached by his Instagram account (@spiral_go), or by email at (philip@speculativeliterature.org).