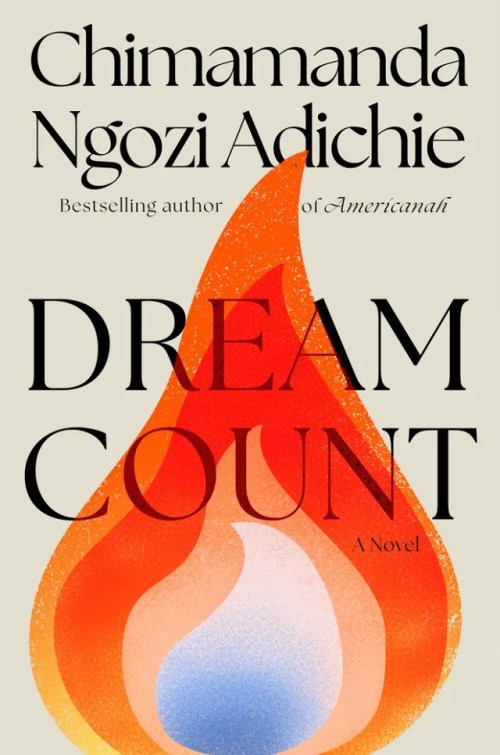

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s last published novel Americanah solidified her presence in modern literature, winning various recognitions and awards, including the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction. Since that time, her nonfiction writing solidified her presence in pop culture too; her 2014 book of essays, We Should All Be Feminists, led to a TED Talk later sampled in Beyoncé’s song “Flawless” and a collaboration with DIOR that produced a classic white T-shirt with the words “We Should All Be Feminists” worn by countless celebrities and spawning knock-offs at a fraction of the cost. So, Adichie’s forthcoming novel came with considerable excitement. And now, Dream Count is here.

In Dream Count, Adichie follows the lives of four Nigerian women in America: Chiamaka, a self-proclaimed travel writer who comes from a wealthy family; Zikora, her best friend, who is financially and professionally successful all on her own yet finds herself falling maddeningly short of personal (a.k.a.: familial) expectations; Kadiatou, a kind and virtuous hotel housekeeper who also works for Chiamaka as she raises her daughter alone while waiting for the love of her life to finish his prison sentence; and Omelogor, Chiamaka’s unabashed, ambitious cousin who left her job as a banker in Nigeria to study pornography in graduate school and start a website to advise men about women.

The book is organized into five sections of multiple chapters, a section for each woman except for Chiamaka, whose sections begin and end the novel. Chiamaka’s and Omelogor’s sections are told from their first-person perspectives, while Zikora’s and Kadiatou’s lives are described in the third-person. It’s also bookended by the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning with Chiamaka quarantined at her house in Maryland and becoming increasingly despondent: “Every morning, I was hesitant to rise, because to get out of bed was to approach again the possibility of sorrow. …This is all there is, this fragile breathing in and out. Where have all the years gone, and have I made the most of life? But what is the final measure for making the most of life, and how would I know if I have?”

These questions follow Chiamaka—and her friends—throughout the book, initiating a sort of assessment, or dream count, that explores the romantic relationships she has had to date. While there is some crossover, each section heavily focuses on its titular character.

Kadiatou’s section is the most comprehensive, with a decades-long timeline that begins in her early childhood and ends with her reeling from a sexual assault later on as an adult, comforted by the three women along with her now-teenaged daughter, Binta. This assault, which is not her first one, occurs when she enters a hotel suite to clean it and the VIP guest who is still there runs at her, naked and erect and forces himself into her mouth. The attack mirrors the real-life story of Nafissatou Diallo, a housekeeper who worked at the Sofitel Hotel in New York City. In 2011, Diallo alleged that she was sexually assaulted by hotel guest Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the French politician and economist who at the time served as the managing director of the International Monetary Fund.

Like Diallo, Kadiatou decides to press charges, surrounded by a flurry of support and encouragement, only to find herself caught up in an excruciating examination of her life and decisions. The case brings all of the women closer together and underscores certain themes found throughout the book—themes of sexuality, control, autonomy, desire, virtue, dominance and submission, and what it means to be successful. In Omelogor’s section, which follows Kadiatou’s, Omelogor says:

When Jide is happy drunk at my dinner parties he boasts about how quickly men fall in love with me…. They laugh and call me iron lady lover and teasingly wonder about the man who will finally make me fall. Jamila, with her sly slanting manner, listened to Jide’s story the first time she heard it, then turned to me to ask, “Do you think you would try harder with men if you didn’t have money?” …I didn’t have money when I was sixteen and told the popular boy, Obinna, who I liked, that I didn’t want to be his girlfriend because I wanted to be free. But Jamila is really saying that money is an armor and she is right. Money is an armor but it is a porous armor. No, money is an armor and it is a porous [armor]. It shields you, feeds you the potent drug of independence, grants you time and choices. …Yet money deceives in how much it cannot prevent, and in what it cannot protect you from.

Dream Count feels a bit like what perhaps a Nigerian, or Nigerian American, version of Sex and The City might be, an examination of sex, love, and relationships (in heterosexual couples) by four similarly aged women, a novel that also provides cultural insights that move beyond stereotypical tropes around immigration, status, and social hierarchy. Like with the show’s best episodes, the book provokes many emotions (in a more intense way, with no disrespect to either), showing how closely intertwined they are—for example, lust and disgust, obedience and rage, horror and humor. Our deep human need for romantic connection creates an endless array of complications—and that we try, or that it’s worth trying anyway. Without meaningful friendships, though, we simply cannot survive.

Adichie’s return to fiction is a poignant reminder of her masterful writing, poetically universal while startlingly acute in its observations. Dream Count is full of resilience, perseverance, and strength, in all their remarkable formats and configurations. Or rather, in all their remarkable formats and configurations as they relate to women, which is to say that the spectrum is even more (in my opinion, because I am a woman) nuanced and spectacular. Each section seems to say: “See all the ways women suffer and yet continue on with grace and power? See how many ways there are to be beautiful and triumphant?”

Yes, and yes, I say back. Dream Count is a balm for past transgressions and current ones, for unique and singular hardships, and for those that seem to keep on repeating.

FICTION

By Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Knopf

Published March 04, 2025

Monika Dziamka is a Polish-American writer and editor living in her hometown of Albuquerque, NM. Visit her at www.monikadziamka.com