Casey Mulligan Walsh’s The Full Catastrophe: All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared seeks to address questions about bereavement and belonging. Walsh comes to this inquiry in earnest at the age of twelve after losing both her parents within a ten-month period. Sent to live with distant relatives, she inwardly struggles during her adolescence to conform to another family’s rules and adjust to a new school and peers: “I became adept at finding ways to fit in. If I alternated between smiling sweetly and proving my worth, I hoped I could strike just the right balance.” Not long after she graduates, she loses her only sibling to a heart attack, and has no remaining immediate relatives.

Walsh copes with her losses by marrying young and starting her own family in her early twenties, and enrolls in a local college, forgoing an opportunity to attend Cornell. Though there is joy during what she terms the “placid middle years” of raising her children, Walsh initially excuses the impacts of her husband’s drinking and his shirking of parental responsibilities: “It’s not ideal. It’s not what I prayed for. But it’s a bargain I’m willing to make to keep my family intact.” Striking a measured balance between scene and interiority, Walsh paints a clear picture of her increasingly abusive marriage. Her attention to setting and references to television shows and songs makes the reader feel that they are observing her family from a room inside the house.

After Walsh finally leaves her husband, she details with vivid recollection custody battles and the testimony of people on both sides. Despite Walsh’s ongoing conflicts with her ex-husband and children, and health and self-esteem challenges, the book shines when she finds comfort in her lighter moments with her family, in supportive friendships, and in song lyrics. “A tiny ray of hope,” she writes, “has worked its way through the cracks, a message from the inside.”

One might expect that hope to disappear when Walsh’s firstborn son, Eric, dies unexpectedly. And though it does not buffer her from the loss, the previous deaths of her parents and brother have made her uniquely resilient. The depiction of the end of her son’s life is harrowing to read but Walsh’s raw honesty about his challenges makes him more sympathetic than if she had chosen to eulogize him in a superficial way. Throughout the book, Eric’s passion and anger, his enjoyment of relentless activity and sports, are brought to life. Her love for him is reflected in her remembrance of their arguments and vivid descriptions of him on the soccer field and in family and yearbook photos.

The Full Catastrophe is a gift for readers wondering how they will get to the other side of their own tragedies. Walsh shares the spiritual insight she discovered to help her through her grief and depicts how she moved towards a happier ending. She prevails in sharing the wisdom gained from everything falling down around her, stating that “true belonging requires me to be myself, embrace my gifts and struggles, and share them without fear. Only in this space do I find the connection I crave and the strength to stand alone.” The memoir is a testament to human resilience and releasing control in the face of heartbreak, and that over time, one can hold the full catastrophe of one’s life—the grief, the joy, and the in-between.

NONFICTION

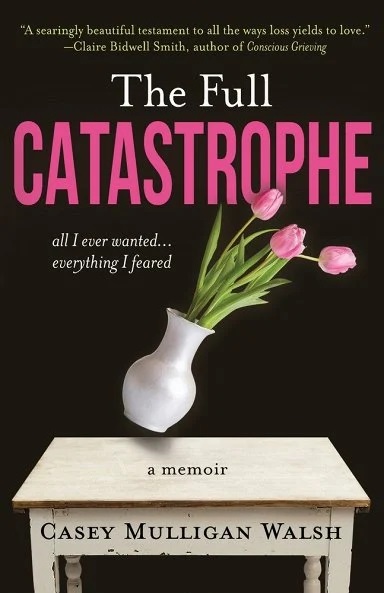

The Full Catastrophe: All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared

By Casey Mulligan Walsh

Motina Books

Published February 18, 2025

Sarah Leibov’s personal essays and book reviews have appeared in Newsweek, Tablet, Lilith, and other publications. You can find her on Twitter @LeibovSarah.