As a teenager born in Cairo and growing up in Doha, Omar El Akkad remembers, “I wanted for the part of the world where I believed there existed a fundamental kind of freedom. The freedom to become something better than what you were born into, the freedom that comes with an inherent fairness of treatment under law and order and social norm, the freedom to read and write and speak without fear.” His ideal of a “free world” is one that El Akkad, like so many others, held onto well into adulthood, believing, also like many others, that for all its flaws, it was an ideal worth trying to fix. “Until the fall of 2023,” he says. “Until the slaughter.”

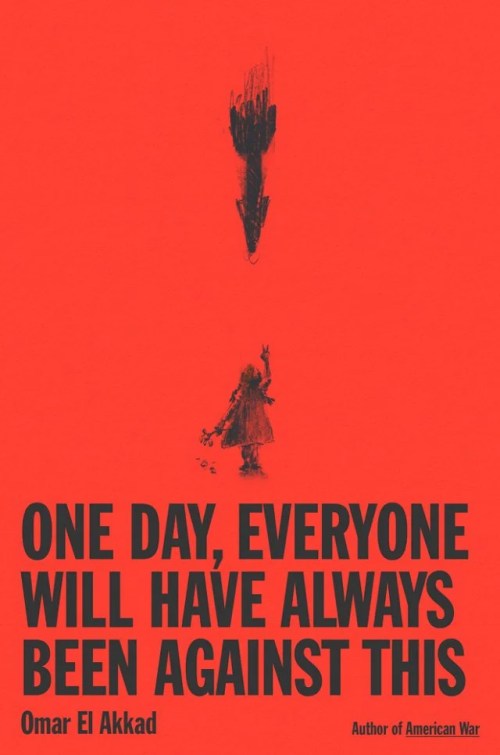

“The slaughter” of Israel’s 2023 counteroffensive against Hamas’ military wing is a focal issue throughout El Akkad’s nonfiction debut, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This. The title, an abbreviated version of a post by the author on X (formerly Twitter), has been viewed over 10.4 million times and sparked fiery commentary from all sides. But rather than limit himself to taking sides in the latest atrocities in Gaza, El Akkad casts a wider criticism of Western imperialism and its associated machinations. His use of the future tense suggests more prophecy than historical documentation. “Once far enough removed, everyone will be properly aghast that any of this was allowed to happen.”

Another recurring theme is the imagery of the war’s growing number of child casualties. El Akkad primes each chapter with graphic descriptions of child victims that include infants whose heads have been severed or pierced by sniper’s bullets and parents burying limbs where bodies have vanished after the strikes. The point is not to look away, though. The contrast with El Akkad’s own children playing safely in the family’s home near Portland, oblivious to the images of carnage in the news that their father follows daily, shows who is forced to suffer imperialist oppression and who is privileged enough to ignore them.

El Akkad worked as a journalist for The Globe and Mail in Canada for nearly a decade, reporting on NATO’s war in Afghanistan, Guantanamo Bay, the Arab Spring, and Black Lives Matter. His novels American War (2017) and What Strange Paradise (2021) won several Canadian literary awards including the Giller Prize for fiction. In One Day, El Akkad interrogates his participation in award ceremonies and events hosted by the literary foundations that recognized him as a way of reconciling the futility of his own success as a professional writer, asking “What is this work we do? What are we good for?”

While depicting the grotesquery of state-sanctioned genocide may be necessary to animate El Akkad’s arguments, the anger pulsing throughout One Day is at its best when directed towards more concrete observations of contradictions in Western policy. Entwining the terminology of global capitalism (foreigners labeled as expats as opposed to illegals, aliens, or economic migrants) with scenes of inaction from arts organizations and governments leads El Akkad to question his personal and professional loyalties in a way that might sound hollow coming from other authors with fewer credentials and less poetic instinct.

Instead, One Day shines with quotable critique that spares no one from scrutiny. Of the literary organizations that canceled readings from Palestinian authors and banned conversation about the war in Gaza during award ceremonies, El Akkad says, “Any institution that prioritizes cashing the checks over calling out the evil is no longer an arts organization. It’s a reputation-laundering firm with a well-read board.” Of the more obvious contradictions touted by conservative politicians, El Akkad calls out their view of America as “an enormously powerful, God-chosen nation in which families are too scared to leave their houses at night.”

Even his own media journalism industry gets heat for cowing to capitalist forces. “Jettisoning the requirement to report news in favor of inciting the rage and fear and hatred of your audience before serving them up ads for guns and bunkers is a perfectly functional business model. It might not be journalism, might be the opposite of journalism, but the checks clear.” Such ruthless critiques leave little room to sympathize with the targets El Akkad chooses to attack. Yet, they allow for a closer examination of the motivations and roles that everyone plays in the failings of a global order that protects the powerful.

At times, his rants against global power structures sound nearly like pedagogies of social justice and resistance outlined by activist philosophers like Paulo Freire or Frantz Fanon. “Active resistance,” El Akkad says, “showing up to protests and speaking out and working to make change even at the smallest levels, the school boards and town councils” matters. Its counterpoint, negative resistance” or “refusing to participate when the act of participation falls below one’s moral threshold,” matters. The way El Akkad presents these directives of resistance alongside the imagery of war and anecdotes of apathy from those personally removed from its horrors implies there is a certain kind of hope to be found in discrete action, an important distinction from how writers like Susan Sontag (Regarding the Pain of Others) and Virginia Woolf (Three Guineas) approached the wars raging in their lifetimes as abstractions from afar. But El Akkad’s memoir isn’t a revolutionary handbook any more than it’s an epistolary response of pacifist feminist idealism. Instead, it’s a call to look into mirrors around the world and ask who is really free.

NONFICTION

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This

By Omar El Akkad

Knopf

Published February 25, 2025

Joe Stanek graduated from West Point and has an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College. He writes about the consequences of war and military culture.