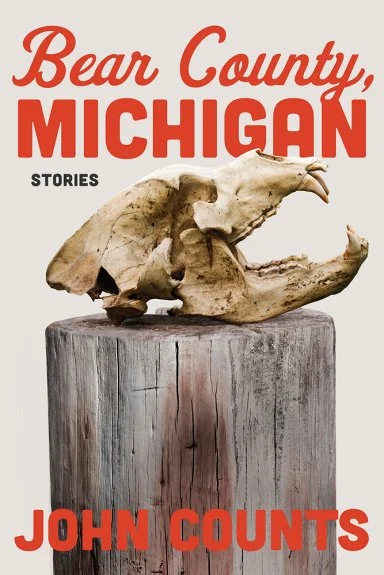

In his debut short story collection, Bear County, Michigan, investigative journalist John Counts gives his readers the vivid, complicated, and wholly human lives of the residents of Bear County, in the hinterlands of Northern Michigan. Whether struggling to gain a foothold, maintaining the faded memories of the good ol’ days, or simply trying to find someone safe to hold them throughout the night, Counts’s characters reflect life not just in the isolated backcountry of the American Midwest, but in the aspects of life all readers can connect with.

Though Bear County is isolated—if you look at the palm of your right hand and point to the middle of your pinky finger, you’re close—Counts’s stories never feel removed, his characters never distant. A woman who collects animal skulls simply wants to be recognized. A teenage sex worker simply wants to know her place in the world. A dying ship captain longs to reconnect to the worlds he left behind. Even an heiress living in Chicago longs to know if there is more to life than brunch.

In eleven stories and one novella, John Counts announces himself as a meditative and generous author in the vein of Jim Harrison and Bonnie Jo Campbell. I had the honor of speaking to him about class, power, conflict, and the desire humans have to be kind, despite being broken.

RS Deeren

You’ve been a Michigan journalist for twenty years. This has rooted you in the real-life stories that have made up life in areas like the ones you’ve depicted in Bear County, Michigan. Fiction isn’t falsehoods but it’s not “real” in the sense journalism is. How has your experience in reportage informed your work as a fiction writer?

John Counts

Fictions are built on the reality our minds have consumed. For me, that has included the stories I’ve covered as a reporter. The type of journalism I’ve been a part of—mostly local crime reporting and investigative reporting—puts you near big characters and big events and skews your perception of the world as this always-dramatic place. I think my stories end up populated by certain types of high-wire people and events.

“Lady of Comfort” is based on a house explosion I covered where an old man died. The trooper on scene winked at me and said the old man had a “lady of comfort.” That was so striking, I needed to use it in a story. “The Hermit” was also pulled straight from a fire I covered one snowy night in Manistee County. A cabin was burning a mile away in the woods, no road in, so the firefighters rode out there on snowmobiles. They told me a hermit was stuck in a cabin and lit the fire as a call for help.

As a fiction writer, I’ve carried those experiences with me and use them to build the stories—just in the same way all writers use their reality to dream up their art. I see my work as realism merged with the mythic. Scour the police reports and sit in court long enough, and you will find the stories in Bear County. But you need the mythic to lift them out of ordinary reality, so they transform into something meaningful.

RS Deeren

The power of this collection comes from multiple voices and perspectives chewing on the same questions. Early on, a rudderless gas station cashier ponders: “A person could only do so much in life… But what to do with a life?” Later, the heiress of a dwindling fortune questions life, stating: “Don’t you think there’s something more to life… we just keep forging endlessly on into the future…” What do you think are the driving forces of the people of Bear County and where do you see them chewing on the same questions? Do they find answers?

John Counts

What drives the good, maladjusted people of Bear County? On the surface perhaps booze, pills, easy money, sex—but these are quick fixes in the scheme of things, and they all know it even if they can’t articulate it. Big Frank wants booze, but he also wants absolution for his guilt and relief from his grief. Debbie wants a baby—but what she really feels is a lack of purpose in her nowhere town. Lillie wants a bear skull—but mostly she wants to ease her loneliness and suffering through her chosen art form. Everyone in Bear County is kind of broken and looking for something that might not exist. Except Shelly in “The Nudists;” she has her shit together. I think she might be the only one I’d lend money to.

RS Deeren

From a writing perspective, you present earnest characters with clear desires: find some pills; bleach a bear skull; get pregnant; earn someone’s vote, etc. These desires, though, lead to more complexity and there is no simplicity in the so-called “simple life” of rural Bear County. How do you elevate the desires of these characters and make them speak to struggles readers outside of these spaces may recognize?

John Counts

There is nothing simple about small-town life, as evidenced by your own wonderful story collection about the Thumb, Enough to Lose. And it’s our job as writers to speak the truths—big and small.

My characters inhabit a very specific world—a small, upper Midwest town where there is a keen sense of the best days—the lumber boom—being in the past. We’re all faced with trying to build a meaningful life in such twisted circumstances. The prevailing sense is that only well-educated people in big cities have rich inner lives and complex problems. The truth is people everywhere are living electric lives, even the gas station cashier. I see fiction and storytelling as ways to explore those spaces buried inside us all, regardless of where we’re at in the world or what we look like or how we love. We all ask ourselves the same questions about life. The souls in my stories just so happen to be trudging through woods, rural communities, and small towns of the American hinterlands—places I know well.

Fiction is a way to explore our differences but also our core humanness. I’ve lived in pretty much all types of places over the years—big cities, small cities, suburbs and small towns. My childhood was spent in Bay City, my formative years in the suburbs and my 20s in big cities like Detroit and Chicago before I fled to rural areas like Manistee, Chelsea, and Whitmore Lake, where I’ve lived the past decade raising my children. But the basic things that drive the most sophisticated urbanites in Chicago’s Gold Coast drive my small-town neighbors (and characters).

RS Deeren

Many of the characters in this collection deal with grief that is both unfathomable yet wholly tangible. They have lost jobs, loved ones, and ways of life that used to fulfill them. Still, some of the most pointed stories have characters grieving the loss of things they never had. In “The Women of Brotherhood,” generations of infertile women grieve motherhoods they’ll never have. In “The Final Voyage,” a daughter grieves a potential relationship with a distant father. What role does grief play in these stories?

John Counts

A balance between joy and sadness in stories is true to human experience. Even in our moments of great happiness, there is always something just out of view reminding us that much of life is loss. And it’s something that’s glossed over quite a bit in some of our cheerier cultural takes on small-town life. Humans are capable of crafty things—airplanes, AirPods—but we can’t outfox death. And that is the true, desperate nature of our condition—and something that is always on my mind as a fiction writer, simply because it’s a shared fear and is something that gets wired into every character. Loss is a great theme of literature. It’s one of those experiences that binds us all together.

RS Deeren

Many of your characters deal with addiction. The opening story, “Big Frank,” shows the titular character busting himself out of rehab for a heartbreak-fueled bender; stories like “Lady of Comfort” highlight how the protagonist’s cocaine habit ties her to a life she doesn’t want. What’s masterful about your stories, though, is that while these addictions may define the circumstances surrounding your characters, they are never fully defined by them. How do you keep your characters from being one-dimensional in this regard?

John Counts

Addiction is a full-blooded, fully dimensional world for me. I’ve been sober for seven years, but for about twenty years before that I drank quite insanely and unheroically. Pills too. I came of age in the Detroit punk scene and creative writing workshops before graduating to newsrooms. Drinking was part of the culture in all of them. It was also a world I was steeped in at work as a police and court reporter. I’d say about seventy to eighty percent of the crimes I covered involved substance abuse of some kind.

People want to feel better when things don’t feel good. It’s as simple as that.

What I learned in recovery is the booze, the drugs, they don’t define us. We are a person outside of it, humans with an affliction.

To capture all that nuance in the craft of fiction involves shooting people off in all sorts of directions at the same time—psychologically, morally, situationally. The booze or drugs are there—but there’s always much more. Yes, Jimmy Blizzard is chasing an Oxy high, but he’s also grieving for his lost family (and perhaps his finger). Big Frank, Grace, Kylie, Jessie Powers all struggle too—and for them, the substances are just one piece in a whole medley of joy and suffering.

RS Deeren

There are many characters in this collection who attempt to take control of small aspects of their lives when economic and social systems control so much of their day-to-days. Many times, this leads a character to their breaking point. Class lines are stark and, with the closing novella “The Standoff,” race plays a crucial factor in how characters like Sheriff Bobbins and Tyrell Winter Bear find and use power in their lives and over the lives of others. How can fiction highlight these power struggles?

John Counts

No one cares about the people in any of the Bear Counties across America, where people are broke, looking for something bigger, trying in some small way to feel significant, to take their power back.

Bear County is an America away from wealthy urban spaces, especially the coastal areas, or the “centers of ambition” as Jim Harrison called them. To the elites, the good folks of Bear County are just sources from which to extract money and votes. As we know, ambition, money, power can be deadly. It’s our job as fiction writers to set forth imaginative scenarios that remind us humans can be humble, kind, and giving, to tell stories that remind us who the real heroes are—generally not the king.

When I was young, I screamed about all this on stages in punk rock bands. What I do now for a day job—investigative and accountability journalism—has roughly the same aim, albeit a little more refined (and effective)—take on the rich and powerful; keep them honest with the truth.

I see Winter Bear as a punk rock hero—the truest of underdogs in a gamed system, a radical who will do anything to take control. Bobbins is on the other side of things and has a different mission—to protect and serve that structure—but he’s lazy and torn about it. Both serve their purpose on opposite sides of an eternal conflict: the crisis of human beings trying to live together despite differences.

RS Deeren

Bear River, compared to Chicago, is a speck on the map, but for the people of Bear County, it’s their city. The smaller communities aren’t monoliths either; they all add to the voice of the collection. In a past interview I did with Bonnie Jo Campbell, I asked her about the growing recognizability of a rural Michigan Literary Voice. What are your thoughts on this and how do you see Bear County, Michigan adding to this voice?

John Counts

I’ve thought a lot about the Michigan Literary Voice (MLV) for many years. I was reared on Michigan authors. I loved Tom McGuane’s The Sporting Club and a lot of his outdoor writing. While not a native, Joyce Carol Oates did great work when she was stationed across the Detroit River in Windsor, most notably with the novel them. I devoured the crime novels of Elmore Leonard as a teen. And I’m half Greek (Mom’s side) and was spellbound with the Jeffrey Eugenides novel Middlesex when it came out.

But my two favorite Michigan literary characters are probably Jim Harrison’s Brown Dog and Campbell’s Margo Crane from Once Upon A River. Both love rivers (an affection I share with them, having grown up trout fishing), and both move me in similar ways—with hope, humor and tears.

Growing up, my dad—who was also a journalist—was drinking buddies with Harrison. We met the great writer one summer at the IGA in Seney when I was about twelve and he invited us up to Grand Marais the next fall to bird hunt. I was lucky enough to spend many autumns with Harrison and his coterie at the Dunes Saloon. As a youngster, I’d sit at the table sipping my Coke and just listen to them talk, not saying much myself. I of course read all of his books too. It was foundational. I had other early mentors, but Harrison’s work was obviously a huge influence. The Bear County stories are riding on the spiritual and narrative coattails of what he and Bonnie Jo Campbell have already established in Michigan—stories about folks living electric lives away from the “centers of ambition,” authoring their own tales even when the world is shoving them in other directions and telling them what to think. That we can get through it all with a little pluck, humor, and grace, no matter what hand we’re dealt. What’s more Midwestern than that?

FICTION

Bear County, Michigan

By John Counts

Triquarterly Books

Published February 15, 2025

RS Deeren’s debut collection of stories, Enough to Lose (Wayne State University Press 2023 is a 2024 Michigan Notable Book. He earned his MFA from Columbia College Chicago and PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He is an assistant professor of creative writing at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee, where he is the fiction editor of Zone 3 Press. Before pursuing writing, he worked in the rural Thumb Region of Michigan as a line cook, a landscaper, a bank teller, and a lumberjack. Find him at www.rsdeeren.com and on BlueSky @rsdeeren.bsky.social.