When Zora Neale Hurston died in 1960, orders were given to clear out her house. The janitor charged with the task took the most expedient way, heaping her personal papers onto a trash fire. Thankfully, a local deputy sheriff saw the smoke and stopped by to investigate. A friend of Hurston, he understood the magnitude of this loss and seized what he could from the fire.

It’s only because of him that we have Hurston’s final novel, The Life of Herod the Great, now available in print more than six decades after her death. Signs of the fire are evident: Ellipses mark words and phrases lost to burns and charred edges, and large sections (including the rather considerable final chapters of the novel) are completely missing.

Despite these losses, we know a great deal about Hurston’s final project. She wrote about it in letters to friends, describing her more than fifteen years researching her “obsession,” as she called it. We know that she originally planned to write nonfiction, but later switched to fiction, and that pre-fire, Herod was a complete manuscript (unlike, say, Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which was incomplete when the author died).

We also know that at several points along the way Hurston had considered earlier versions as “final.” Herod had already gone through rounds of submission and rejection by her editor and other publishers. Perhaps Hurston planned to continue her revisions, or maybe she had given up on it but could not bring herself to destroy it. Regardless, Herod is an important piece, and the newly published edition (as well as the excellent scholarly commentary by editor Dr. Deborah Plant) is an invaluable artifact for Hurston specialists and historians of American literature.

But what can the more casual reader expect to find in this historic draft-in-progress? Herod is an odd duck—a sprawling piece of biofiction, an epic recounting of that notorious “baddie” of the Christmas story. Opening with his first big achievement, the defeat of a local warlord, Herod hopscotches from triumph to triumph, pausing to illuminate his relations with his family, two of his wives, his friends, and a number of world leaders.

What you won’t find is the best-known aspect of Herod’s lore, the so-called “Slaughter of the Innocents” recounted in the Christmas story from the Gospel of Matthew. Historians agree that no such decree existed, and that Herod likely died a few years prior to Jesus’ birth. That Hurston neglects the anecdote is more than deliberate; it’s the crux of her project. A trained folklorist, she understood the contours of shared history that so often strayed from historical fact. Hence Hurston’s mission with this final work—to recuperate Herod from these misrepresentations—and her deep dive into the research to convey a more historically accurate portrait of Herod in the context of his time.

But in transforming research into fiction, Hurston stumbles. The aims of revisionist history are not inevitably anathema to writing powerful fiction. Hilary Mantel successfully undertook a similar project in her Thomas Cromwell novels, but her goals were different, and more amenable to the tastes of twenty-first-century readers. Mantel did not so much ask the reader to praise the subject as to understand him. Her Cromwell is psychologically complex and compelling in his humanity.

Hurston’s Herod has a different goal: to recognize and celebrate the achievements of a Great Man writ large. To do this, she offers an intensely detailed account of Herod’s time—the politics, culture, and recent history. In doing so, she argues (and has her characters argue) that Herod was no more despotic, no more of a tyrant, than other rulers of his time. She carefully delineates the rival factions for Herod’s power—the priestly class, chiefly, but also factions in Rome and world historical figures such as Cleopatra—to show Herod as very much a victim of competing agendas and nefarious intent.

The result, while painstaking, is less than successful as a novel. Details come fast and thick, and a reader’s eye can’t help but spin at the parade of characters and confusing tangle of family lineages. To say Hurston argues for a revision of Herod is one sign of the problem: much of the dialogue consists of debates about him or defenses of his actions as fitting for his culture. Hurston makes the same arguments much more persuasively in the introduction, which is synthesized from her letters by Plant. The absence of such persuasiveness in the novel itself is yet another indication that nonfiction might have better served her aims.

But more concerning is Hurston’s rendition of Herod as a character. Hurston offers a dazzling but flat paragon of kingly virtue. He has no flaws, no room for growth, no internal tensions. His inner life is almost nowhere to be found. Instead, Hurston baldly reports his greatness, with the narrator, other characters, and choric representations from “the people” as her mouthpiece. Herod is great, this we know, because Hurston tells us so.

Then there is the plot. Over and over, Herod faces political and personal challenges, nearly all of which he easily surmounts. There are privations and sufferings, yes, but with no threat of failure, no promise of growth. All Herod’s challenges are external. When life gives him lemons, he inexorably makes lemonade.

Hurston was more than equal to the task of making literature from history, as a quick comparison to her 1939 novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain, demonstrates. In her commentary, Plant refers to Herod as a sequel to that earlier work. The connection makes sense: Many Bible scholars view Herod’s brief, notorious appearance in the New Testament as an attempt to link Moses and Jesus as spiritual brothers, with Pharaoh and Herod as twin villains.

But the two works couldn’t be more different. In Moses, Hurston the novelist is in the ascendant. She opens with an arresting evocation of women laboring in childbirth in remote caves and hidden rooms, terrified of the state agents set to murder any boy-child upon delivery. Next, Hurston zooms in on Moses’ family: his father, worried about his wife’s impending labor, and his mother, struggling to give birth in silence while secret police prowl the streets outside. Hurston’s storytelling is visceral. In a masterstroke, she puts the dialect of Blacks of the American South in the mouths of Hebrew slaves. The result is powerful, affecting, and aesthetically adventurous.

In Herod, this artistic daring is replaced by a more grandiose, stilted, old-fashioned style. Proclamations abound. The dialogue recalls the sword-and-sandal epics of the ’50s. We never feel immediate danger, never perceive Herod as a living, breathing person. The paucity of historical information about Moses seems to have activated Hurston’s powerful creative imagination; the surfeit of research about Herod stifled her.

To say that Hurston hadn’t cracked the code in Herod doesn’t mean she never would. At her death, she may have had plans for further revisions. Perhaps she would find her way to a deeper characterization, or maybe she would have returned to her original plan to redeem Herod through a straightforward biography. We simply cannot know.

Regardless, what we have in these pages is a monument to Hurston’s passionate, piercing intellect, fired by curiosity and persistence. It is invaluable to Hurston scholars, offering a glimpse into her creative process, her abiding academic and artistic passions, her unflagging drive to keep creating art and scholarship.

Anyone who has gone down the rabbit hole of research knows how compelling such a path can be. That Hurston’s journey spanned more than a decade and a half and culminated in a yet-to-be-perfected manuscript is in itself a testament to her literary and scholarly legacy. Despite its flaws, this unfinished novel remains a worthy and important object of study for those who are passionate about American literature.

FICTION

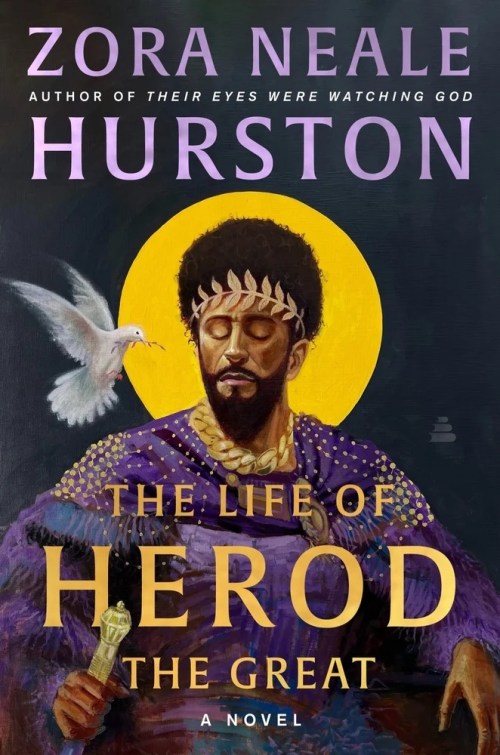

The Life of Herod the Great

By Zora Neale Hurston

Amistad Press

Published January 7, 2025

Kay Daly was born outside of Los Angeles, California, and lives in Chicago, Illinois. She holds a Ph.D. in English Literature from Northwestern University, with a specialization in early modern English literature. For the past 20 years, she has worked as a professional writer and editor for a range of publications, companies, and nonprofit organizations, including TimeOut Chicago, the Metropolitan Opera, and WNET New York Public Media, and currently serves as communications specialist for an education nonprofit. Her debut novel, "Wilton House," will be published in spring 2027 by Regal House Publishing. Visit her website at https://www.kaydalywriter.com/