The easiest respite from wilting in my sweaty Chicago apartment this summer—the hottest on record—was to jump in the lake. On one such August day, I floated on my back, enjoying the late afternoon shadows cast by nearby apartment buildings. The cold water and city gloom cleared my heat haze and I marveled at the lake’s vastness. The Great Lakes System, which includes Lake Michigan plus Erie, Huron, Ontario, and Superior, is one of the world’s largest surface freshwater ecosystems. I was humbled and grateful to be refreshed, flopping around in our region’s drinking water. Recalling the shocking moment I saw a 45-page bottled water menu in Los Angeles some years ago, I felt fortunate to be able to enjoy the water’s beauty and abundance in this way. Lake Michigan got a tiny bit salty that afternoon.

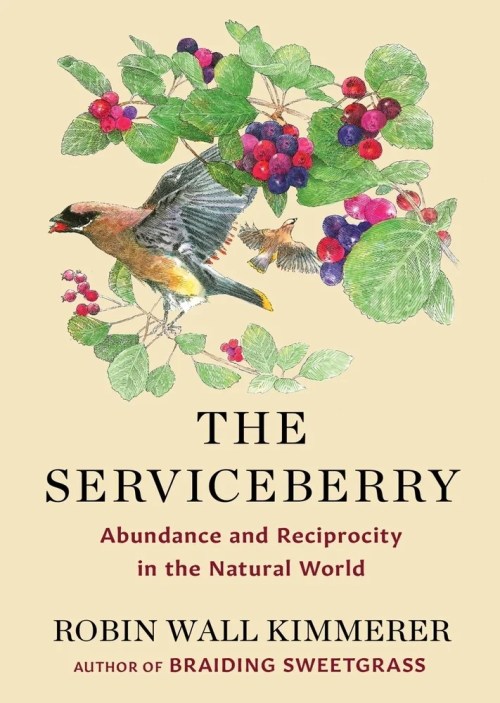

Abundance in nature is the focus of Indigenous botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s new book, The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. This is the author’s first book in over a decade and it expands upon her message from the successful Braiding Sweetgrass (2013). As in her first book, the author engages wisdom from Indigenous teachings to address how we can enrich the natural world and our relationships. Under a hundred pages, The Serviceberry is beautifully written with illustrations by John Burgoyne. Like me, you might pass the afternoon reading the book in one sitting, entranced by the author’s hopeful words for how to combat ecological destruction and the isolation and purposelessness so many people experience in this digitally oriented, self-interested world.

The serviceberry plant is known as a calendar plant, meaning it is faithful to seasonal weather patterns.[i] For Indigenous North Americans, the serviceberry has been an important means for synchronizing movement through their homelands with people moving to where the food is ready: “Instead of changing the land to suit their convenience, they changed themselves.”[ii] This act of eating according to what is in season and available is a way of honoring abundance, says the author.

There are several species of the plant, which is native to Minnesota and other parts of North America, including the Great Lakes region. The plant bears a sweet fruit that is part of the Indigenous foodways wherever they grow. Robin Wall Kimmerer, who belongs to the Potawatomi Nation, one of the Anishinaabe peoples of the Great Lakes region, grew up eating the berries, which are regarded as the land’s gift. In accepting the serviceberry as a gift, people express their gratitude. Doing so means more than a polite “thank you.” Gratitude means taking responsibility for sharing and demonstrating respect and reciprocity.[iii] This worldview means recognizing what the author calls “enoughness”—taking only what one needs. This, she says, is a “radical act in an economy that is always urging us to consume more.”[iv]

In The Serviceberry, Robin Wall Kimmerer asks readers to question capitalism’s accepted wisdom that competition between individuals leads to success in economics and in natural selection among plants and animals. The author, a professor and 2022 MacArthur Fellow, posits that scientific evidence has been growing to support the idea that “mutualism and cooperation also play a major role in evolution and enhance ecological well-being.”[v] What would it mean, she asks, if we treated the natural world as part of a “gift economy” instead of as resources? How might our ecosystem and personal relationships transform if we viewed the natural world as a source of gifts rather than as stuff to be extracted from the Earth and commodified?

Robin Wall Kimmerer characterizes capitalism as manufacturing scarcity. Though she regards the natural world as being abundant, she acknowledges that by commodifying and exploiting resources, we end up with real scarcity and “shortages of food and clean water, breathable air, and fertile soil.”[vi] Gift economies, by contrast, are characterized by treating the Earth’s abundance as things owned by no one. In such an economy, water would not be bottled and sold to be selected by a “water sommelier” for an upscale restaurant. Instead, it would be freely given and those who enjoyed it would be responsible for using only what they need and keeping it clean.

Remnants of gift economies have endured in Indigenous societies all over the world. In these contexts, water is treated as “sacred and people have a moral responsibility to care for it, to keep it flowing.”[vii] This means accumulating and using only what one needs and sharing with other members of the community. According to the author, sharing strengthens social bonds and community security is built from the ties of reciprocity.[viii] In an individualistic society, there is a tendency to hoard for one’s own personal use and an imagined future where there is not enough. By contrast in a gift economy, when someone has enough, they share with others and know that if the need should arise, someone will do the same for them.

[i] The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World, p. 3

[ii] Ibid

[iii] p. 8

[iv] p. 11

[v] p. 71

[vi] p. 74

[vii] Ibid

[viii] pp. 44-45

NONFICTION

The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World

By Robin Wall Kimmerer

Scribner Book Company

Published November 19, 2024

Lori Hall-Araujo is a communication scholar and visual artist.