Yuri Herrera lives between cities, languages, and cultures. As a professor at Tulane University, he has lived for many years in New Orleans—a melting pot of world cultures—while returning to his native Mexico 7-8 times per year. Herrera’s comfort occupying the “in-between” is, perhaps, best exemplified by his fiction. His 2016 Best Translated Book Award for Fiction winner, Signs Preceding the End of the World, was translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman and explored the border crossings people make in space and in their minds. Herrera’s latest book continues his sensitive interrogation of crossings of all kinds. And it’s a love letter—to a certain vibrant polyglot American city, absolutely, but also to the people and places in-between.

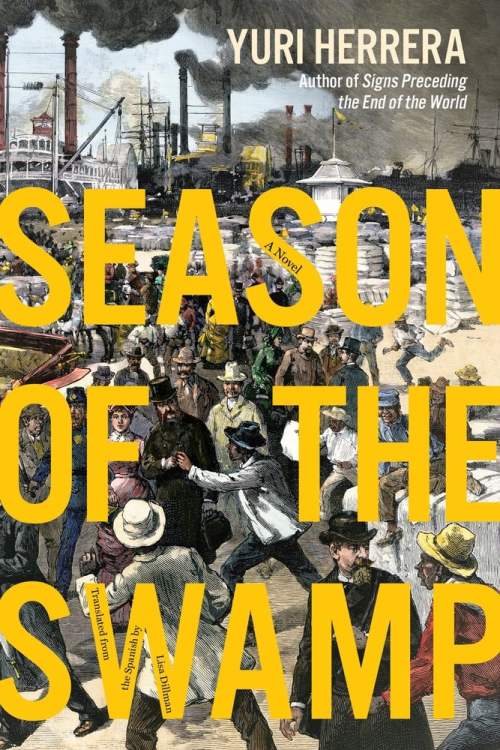

Set in 1853, Season of the Swamp (also translated by Dillman) is an immersive work of speculative fiction about Benito Juárez’s eighteen months of exile in New Orleans. As Juárez plots with other rebels to return to Mexico, where he’ll eventually become the first indigenous head of state, he walks the streets of the old quarter, reads the paper, and overhears other revolutionaries’ conversations in coffee shops. Season of the Swamp is vividly imagined and tenderly gritty. While its characters are especially well drawn, the book shines brightest in the secretive recesses of Herrera’s mid-19th-century New Orleans. This is a city of opposites: of violence and beauty, despair and hope, destruction and creation. I read it in a day.

On a Friday afternoon in August, Herrera and I chatted via Zoom about the tools and experiences that prepared him to write this book, which eventually led us to discuss hope, rebellion, and reinvention.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Elizabeth McNeill

You open the novel with a note about the New Orleans-shaped gap in Benito Juárez’s biography. When did you know you wanted to write a book about his eighteen months in New Orleans? Why were you drawn to this story at this moment?

Yuri Herrera

I tend to marinate my books for a long time. I think about them for a long time. I take a lot of notes. I try not to rush them. And once I’m sure about what I’m going to do, I write them in a few months.

This book was preceded by two long periods of preparation. When I arrived here, a friend of mine who was already living here told me, “I’ve been looking for Benito Juárez’s house, but I can’t find it.” In that moment, I thought, “Oh yeah, he was here.” This period appears in every single Benito Juárez biography. It always says that this was a very important period, but nobody has details. It’s forgotten!

So, I started thinking about it, and several things happened that eventually led me to a place where I was ready to write it. The first one is that I have been in this city enough time to know it in different ways. When you stay in a place for long enough, you can see the good and the bad, the terrible and the marvelous. New Orleans is all those things. It’s incredibly violent, it’s incredibly creative, it’s super beautiful, and it’s a tough, tough city. After a while, I had my own opinions, and my own experiences, and my own ghosts in this city. That’s the main material when you’re doing literature. Not only your literary influences and the research you might do for a book, but what has been growing inside you. For me, that’s the most important thing. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing about Martians or Hobbits or vampires; you’re always writing about your family and your neighbors and yourself. You just find other ways to express it. So, even though it is a novel about Benito Juárez and about New Orleans, it’s a novel about myself.

But also, right before this, I wrote two books almost at the same time. Somehow, they were what allowed me to prepare for this book. One was Ten Planets, which is a science fiction short story collection. When you write science fiction—or when you write speculative fiction (the difference is not so clear nowadays)—you are in charge of the universe. You can do whatever you want. You can make up planets, you can make up languages, you can make up habits. And even if you’re talking about your surroundings, you’re free to do this. At the same time, I was preparing my other book, A Silent Fury: The El Bordo Mine Fire, which is a historical narrative about a fire that killed a lot of miners in my hometown in the 1920s. On the one hand, I had absolute freedom to do whatever I want, and on the other hand, I had this book that was limited and empowered by facts, documents. I had these two tools that were perfect for this kind of book. It was about the research on Juárez’s life and the research on News Orleans life, but also there was a void I had to fill, not just with information but with my imagination based on my research.

Elizabeth McNeill

One of the most remarkable parts of Season of the Swamp are the stories Juárez comes across in the papers or in his walks around the city. They make the world you’ve built on the page feel so alive and distinctive. They’re stories of arrests and fires and deaths and operas in the city—and they function as a sort of how-not-to guide for surviving in the city.

Yuri Herrera

That would be a great book! We should plan a series!

Elizabeth McNeill

[laughs] Definitely! So, I’d love to know: How did you find these stories? What did the research process look like for you as a New Orleans resident?

Yuri Herrera

This was really fun! The Times-Picayune, the local newspaper, is digitized, even from that time. I read the newspaper from the day he arrived until the day he left. There’s a lot of things in the newspaper, especially a lot of commercial news: ships that are departing, ships that are arriving. What I decided to do was to read the criminal section of the newspaper because that is about the street life. It’s not just constrained to certain institutions. It speaks to life outside of the frames of “normal life.” Every single story you see there is documented. It’s either in The Times-Picayune, this section, or in one of the other books that I researched (but mostly, they come from the newspaper). I used the stories as they appear in the newspaper more or less in the same period in which the story’s happening in the novel.

I also got the names of the other protagonists. Thisbee Martin: I found that name in a story. It’s the story of a woman who was helping a person who was enslaved escape, and she was arrested. I don’t have more about this person, but I said, “Oh, this is my protagonist!” This is a real person and it’s very likely Juárez could have met people like this.

I did a lot of research about life in New Orleans: about the music, about the race relations, about the indigenous peoples (back then, they still had a little bit of influence and much more presence). There’s a bunch of really good books about the city, one specifically about slavery called The Half Has Never Been Told. And there’s The World That Made New Orleans. In these books, I found stories and the general context of the stories. Now and then, I filled the texture needed for these stories with my own experience. In that sense, it comes from three places: from the newspaper, from the books, and from my own experience.

Elizabeth McNeill

I read Season of the Swamp as being deeply concerned with how to change a structure that’s designed to crush certain people into submission. For instance, Juárez, as an attorney and an exile, can see the violent machinations of American law and is especially horrified by the human trafficking throughout the city. But New Orleans—“forever renewing itself as though the swamp made no matter”—also seems to exist right on that fine line between danger and hope. If change is going to happen anywhere, it’s going to be here. What do you think mid-19th-century New Orleans offers us as a potentially hopeful, or potentially cautionary, model?

Yuri Herrera

This is a good example of where you can go when you’re supposed to have absolutely no options. You build a city on top of a swamp filled with alligators and snakes, and then you—now I’m talking from the perspective of the colonizers—you send to this place the outcasts, the people you don’t want. That’s what the French did: they sent prostitutes, they sent criminals. And then, you fill the city with legions of human beings kidnapped from Africa and thrown here to do the toughest possible jobs in inhumane conditions. And then you have all the people who come from Haiti.

So, you have this combination of outcasts apparently with no hope. And I would say that’s precisely the moment and the kind of place where hope makes sense. When you have everything, you don’t need hope. You’re just drowning in excess. And here—what was there, what’s still here—is an excess of other stuff: an excess of heat, an excess of sensuality. And that brings something else that some people define as “resilience.” But I don’t think it’s that. I don’t like that word, because “resilience” sounds like you can do whatever you want to some other people and they are just gonna come back. I don’t think it’s just that, it’s just taking all that shit, all that violence. It’s being a nonconformist. Being a rebel in a different way, you know? It’s not about being a rebel in belligerent terms—in terms of war—but being a rebel in deciding to live your life on your own terms, in spite of being thrown into a place where you’re supposed to be forgotten.

I always say, “New Orleans is the original queer.” Now people have a certain understanding of queerness. But this is a place where men have been dressing like women and women have been dressing like men for 200 years, you know? Where people have been creating new forms of music. Where people have been disrespecting the classic Western culture and twisting it and making it into something new. In order to do that, they used the lowest of the lowest, which was the music brought over by people who were not citizens, people who were barely “humans.” The Black population created one of the most important cultural movements in the history of the world.

That is not resilience! That is rebellion. That is a way of reinventing yourself.

What Europeans and 19th-century Americans did to the Africans back then was a holocaust, was a sort of end of the world, for many peoples. But they decided not to just be victims.

New Orleans is a paradox. On the one hand, you have all the parts of the city that have barely changed, that you can see are the same streets, the same buildings, the same street names. At the same time, it has embraced tradition not as a repetition of certain manic habits or certain ways of doing things. But tradition as a sort of cannibalism of the past, in order to keep it alive in a new form. New Orleans is always taking something from what it has been and incorporating new things. To use a metaphor, that’s because the city is built on top of a floor that is always moving, you know? So, you have to keep moving. And to keep moving means different things. Maybe that’s why there’s so much dance here.

Elizabeth McNeill

Could you talk about the glyph of the bird walking one way and looking the other? It opens and closes the novel, and it means different things for different characters. What does that glyph mean to you?

Yuri Herrera

I found that in one of the books about the racial relations and slavery. It was very common among the African population here. Even when they were losing their language, were being stripped of their heritage, there were certain things they were able to keep. One of them was the music, certain words, and certain images. And this image was prevalent among many people not as a sort of secret society, but just as something in-common that was, in that way, self-explanatory.

Because that is the image of a bird that is going forward while, at the same time, not losing sight of the place from where it’s coming. I think that’s a powerful thing to explain what we were just talking about: how tradition and culture is understood here. Not as something that belongs in a museum, but something that you feed from the past and you just keep going. Not marble culture, in the sense of the great works, the great masters. Yes, there’s great works and great masters, but it’s just something that allows you to keep going.

But also, as a symbol in the novel, that was important for me in terms of what defines a lot of the richness of News Orleans, which is that New Orleans erases the border between low culture and high culture. The low culture of New Orleans is the very high culture not only of the city, but of this country. This city has the best food in the country, and it comes from the street! It has created this music that influenced the whole world, and it comes from the street! And this glyph, this kind of image, becoming a way of creating community, a way of stating something about your identity, is for me a synthesis—just that little glyph!—of what a lot of people consider the spirit of this city, you know? Something that belongs to many people, and something that synthesizes very complex ways of understanding the world.

FICTION

Season of the Swamp

Yuri Herrera, t.r. Lisa Dillman

Graywolf Press

Published October 1st, 2024

Elizabeth McNeill is a Florida-born book nerd who now writes and edits in the Midwest. Until recently, she served as a Daily Editor at the Chicago Review of Books, where she ran the feature series "Checking out Historical Chicago." Her writing can also be found in Electric Literature, Oh Reader, Full Stop, Cleveland Review of Books, Rain Taxi Review of Books, Hopscotch Translation, and Mid-Level Management Literary Magazine. You can find her book musings at her website, www.elizabethamcneill.com.