A 62-year-old author and professor, Farhad Pirbal started his life in Kurdistan, left to study in Paris at the Sorbonne, and then returned, forming a cultural center. He has become well-known as much for his public stunts as he is for his experimental literary work and genius. He fosters an active social media following, ranting and posting about his antics (which have included arson). Yet despite being such a dynamic celebrity figure, little of his work has been translated into English—which is what makes this new collection such a treat.

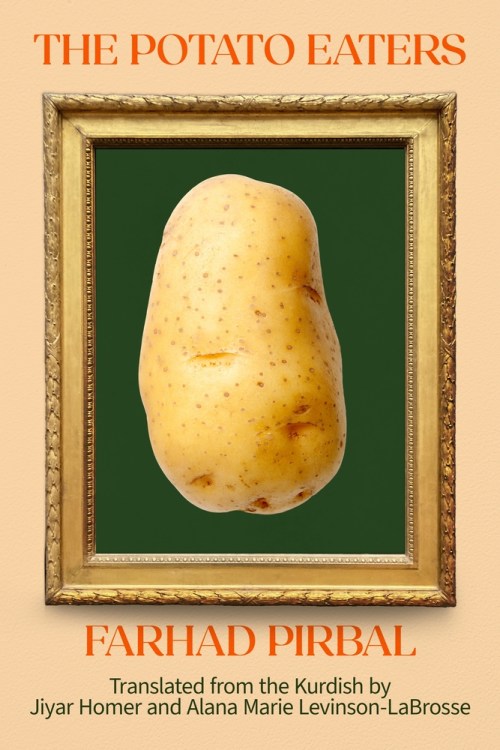

The Potato Eaters, translated from the Kurdish by Jiyar Homer and Alana Marie Levinson-LaBrosse, is a collection of tales that highlight stark loneliness, isolation, and displacement. Pirbal’s protagonists are refugees, runaways, or returning youths who no longer recognize their homes. They are all caught somewhere between: in a dangerous whirlpool between what was once home and the place or community that now rejects them, despite their presence.

In the title story “The Potato Eaters,” Fereydun returns home after years away making his fortune. In his absence, the town has become obsessed with potatoes in light of plague and famine. They eat only potatoes, even drinking potato water through the winters. When Feredyun surprises them with what he brought home from abroad—a bag full of gold—they’re puzzled. One by one, each family member confirms with Feredyun that he did not in fact bring them any potatoes from abroad. And one by one, they condemn him for not doing so.

It’s certainly not the only story that employs this. In “A Refugee,” a man in Munich is questioned and then arrested for eating 10 bananas and throwing their peels on the sidewalk; Perbal recites a chant or prayer that repeats and repeats again with every accusation and summary and defense as the store owner yells at the refugee, as the police arrest him, as he denies what he did. What is the use of this repeating? It sets a mantra, it highlights, as the protagonist of “The Potato Eaters” calls it, “the absurdity of it all.” And does it matter what the refugee has done? Replace the banana mantra with anything at all, and the absurdity remains that a young refugee without residency is arrested for something nonsensical. Take away the potatoes, and a young man has returned home with something of a different value than what his family expected, and the one person who would have appreciated it—his mother—has left this world, gone while he was away.

The repetitive nature of the stories is sometimes played up for humor, or for evoking the mood of song, or fairytale. But it also invokes a bitter sense of inevitability. Of an irony, the bitter truth of trying to escape a loop that is impossible to escape. Of the absurdity, heightened.

Whether leaving or returning, all of the characters seem to face a painful gap between past and present, a gap that seemingly can’t be bridged. A man sees his old, affectionate friend in a dingy bar. After years of hoping to see the friend again, he does, but the friend is disheveled, drunk, disdained. Another returns from years of revolution hoping to find a normal life and his old lover, but instead only finds an old woman whose awkward mumbling he cannot understand—“She wanted me to understand and I wanted to understand; we couldn’t. I wanted her to understand and she wanted to understand; we couldn’t.” He isn’t even able to ask properly about his former lover.

In one haunting scene, a young man, kicked out by his father, a stranger in his own city, writes in a dark hotel room. “How can you write the stories of millions of starving, displaced, friendless, abandoned people? …how can you write something like that and settle your unsettled heart? Ah, God, how long can a human body weep before it runs dry? You write through the tears. You still write.” Perhaps that’s what Pirbal is doing throughout all of this. Pirbal feels the weight of many stories on his shoulders. All he can do is keep writing.

The book as a whole radiates with a dark humor, bitter and poignant, but perhaps none of the stories demonstrate this as well as “Schizophrenia,” a choose-your-own-adventure style story with no true ending. Bakhtiyar is mad, and possibly going to be committed to a psychology ward. He is going mad because of the trap he is in: waiting for residency, endlessly, with no finality in sight, with no money or freedom to live on in the meantime.

The poem loops, and again and again comes to the same points: if nothing changes, Bakhtiyar will be locked up. He must either go home or go mad. Again and again, it comes back to the people we decide are mad, asked whether they would go home if they recovered, who answer: “With all my heart. I long to get back to my mothers’ arms.” It always returns to Bakhtiyar’s wish for home, longing for it, but it never gets him there. Back at home, his family thinks he is doing well. His mother sees refugees like him, and never realizes her son might be in the same predicament. He cannot go home, he cannot keep waiting.

And so the story loops and loops, its events inevitable. It can only end when the reader decides they’re tired of reading it, but Bakhtiyar will never escape the circle he’s in. What gives us the right to turn our eyes away, to uncomfortably leave his despair behind us? It’s a vivid, awful story of collapse, of the way that our systems collapse and fall apart around the refugees who are left to wait, to hope, with no support or promise of change, who are then condemned for what might be an inevitable falling-apart. The reader has to decide when to step away, and it isn’t easy to do. We leave Bakhtiyar behind when we do, cycling, swirling in a whirlpool of despair and lost hope.

In “The Deserter,” a soldier misplaces his leg. The corporal insists he simply replace it with another discarded leg. When he gets a letter from his own leg, who urges him to follow it away from battle, he answers sadly that it’s too late for him to do so. He and his generation are meant to lose things in these battles, parts of themselves, thanks to the decisions of the governments above. The bitter ironies cast against the rich, anxious longing of the protagonists make Pirbal’s short stories expressions of genius, evoking those same pained emotions, leaving the readers heartbroken and thoughtful in all the right ways.

FICTION

By Farhad Pirbal

Translated by Jiyar Homer and Alana Marie Levinson-Labrosse

Deep Vellum Publishing

Published on July 9, 2024

Leah Rachel von Essen is a freelance editor and book reviewer who lives on the South Side of Chicago with her cat, Ms Nellie Bly. A senior contributor at Book Riot, and a reviewer for Booklist and Chicago Review of Books, Leah focuses her writings on books in translation, fantasy, genre-bending fiction, chronic illness, and fatphobia, among other topics. Her blog, While Reading and Walking, was founded in 2015, and boasts more than 15,000 dedicated followers across platforms. Learn more about Leah at leahrachelvonessen.com or visit her blog at whilereadingandwalking.com.