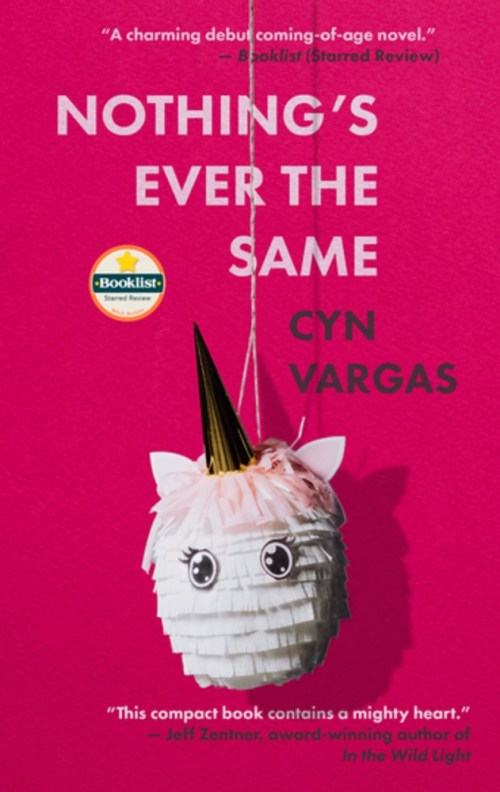

When I talked to Cyn Vargas a few weeks ago, she was ready to paint her nails to match the bright magenta cover of her latest book, a novella titled Nothing’s Ever the Same.

“I don’t know,” she said with that big smile I think she’s known for, “maybe it’s cheesy.” I assured her it was not—if I had a book coming out with such a cool cover, I know I’d do exactly the same thing.

At the heart of Nothing’s Ever the Same is Itzel, a teenager with a lot on her mind. It’s her thirteenth birthday, and her father has a heart attack, then she learns her parents’ marriage may be on the brink; and later, as if things can’t get worse, she develops a crush on a friend.

Nothing’s Ever the Same is full of big emotions: some, of course, that are unique to the particular angst and anxiety of being a teenager, and Vargas captures those feelings well. Her debut short story collection, “On the Way,” was one of Newcity Lit’s top five fiction books by Chicago authors, and received starred reviews from Bustle, Library Journal, and Shelf Awareness. But Vargas is humble, and exudes kindness and generosity as a writer and, it seems, as a human being.

“In my favorite short stories, I still think about what happened to [the characters] after the last page,” she said. “If you believe they’re real, they’ve touched some kind of chord. And so maybe I just want people to still carry Itzel and her family with them after they’re done reading.”

I was thrilled to speak with Cyn about finding an audience, being a teenager, and (how we hope) our favorite stories and characters will live on—even after a book’s final page.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Ruby Rosenthal

You do such a great job with emotions in this book, I feel like you really capture what it’s like to be a 13 year old.

Cyn Vargas

Many kids don’t know how to express themselves, right? Except if it’s through analogies, which is why I use a lot of analogies when I do young narrators, because that’s how they see the world. They can’t sit down and process their feelings and say, “this is how I feel” like we would when we’re in therapy. It’s not just coming of age, but it’s coming of age through survival.

I want people to want to root for her to get through this, to root for her to say something, so she can get this heaviness off of her. And so it was important for me to show that yes, she’s caring a lot—but she’s not breaking. When you share things that are heavy with you, you’re actually asking that other person to carry it a little bit for you at that time, so that you can break, right? That’s why I think people break down crying when they tell something heavy to somebody, that person is not carrying it for you—they’re borrowing it, they’re taking it from you for a little bit of time, so that you can have that emotion you need to feel vulnerable, and then they’re giving it back because it’s not their responsibility to carry it.

I wanted her to do that with the reader— in a way the reader is helping her carry this, because we know as the reader, she’s not alone. But she, as a 13-year-old, doesn’t know that. I know it’s in first person, but it’s also like a very close third; I would hope the reader [would say], “I’m helping you carry this by reading it, as you’re sharing your story. ”

Ruby Rosenthal

When you were writing this book, what kind of audience did you have in mind?

Cyn Vargas

Anytime I write a first draft it’s for me, and I believe the first draft should really just be for the writer—that’s when you can have fun, when there’s so much in your head, you can’t write fast enough. Anything besides the first draft is in order for an audience to understand what I want them to receive, right? It’s my job to look at structure, if the dialogue makes sense, if the pacing is on par. I don’t think of my audience as a specific race, or a specific gender, or age, or class. I just want an audience that appreciates reading good work.

I’ve received feedback that my writing has helped people, or has affected people, and so my audience are those people that want to be able to read a good story, a story possibly by the first Latina writer they’ve ever read. Or for you know, other Latinos they want to write. Especially growing up, [watching TV], it was like the only [Latinas featured] were maids. If there’s no one that looks like you, at the top or in different places, why would you think you can get there? And so I feel like part of my responsibility as a Latina author is to let other Latina writers know that they can do it.

Ruby Rosenthal

Why did you choose a young narrator for this book?

Cyn Vargas

I think part of it is that there’s always some truth in fiction, whether we’re conscious of it or not. I truly believe that authors and writers are catalysts for the story. The stories aren’t ours, the stories are just using us to come through to get on the page, but we have to be able to have that distance—even if we relate to that narrator in some kind of way—to have the narrator be the one that tells us what the story is going to be.

Especially in grad school, it was probably obvious to people who know me why I’m writing stories like this, but to me, it wasn’t—I was just exploring what was on my mind at the time. And with this narrator I wanted to explore something I’d never explored: what if a father could be forgiven for what they did? What if this adolescent grew up with both parents, what would that look like?

Ruby Rosenthal

I’m really interested in what you said about how sometimes, as writers, we aren’t even aware of why we’re writing what we are—was grad school the first time you were cognizant of this?

Cyn Vargas

A lot of the time I think creativity and being an artist is an expression of how we feel inside, showing it to the world outside. Maybe we think it’s for ourselves, and maybe we think it’s for someone else, but I think a lot of the time, it really is just a projection of what we have experienced or what we have gone through.

I think when we write stories that are very close to us—but with a certain distance that they are their own—something about the story is going to relate to the author in some way. If it’s fiction, don’t ask me what’s real (laughs). But I do think there’s just something little that writers put into their work, and it’s not our responsibility to tell people what that is.

When stories really work on the page, I think it’s for two reasons: one, there’s a ton of hard work behind it, and revision, in order for the audience to get it in the way we want them to receive it. But there’s also a part of us that we leave in these stories, and that’s why some stories hit harder with some people. We’re being vulnerable in ways that may not be apparent to us right away or to the reader, but it’s the thing that people say, “oh, there’s something about it that I relate to,” so maybe we can’t put words to it, but it’s there.

I think starting out you may not realize how much of ourselves we put in our work. That’s why some stories don’t work, we’re too close to them. It’s too raw. And when stories are too raw, we cannot see it clearly. And we’re then especially in fiction, it’s not our story that we’re not telling our story—we’re telling someone else’s. So if it’s too raw, it doesn’t work. But when you create the distance, then it really allows other people into a world where they can sort of tap into that.

Ruby Rosenthal

Itzel refers to her parents as “Mom” and “Dad,” but refers to her other family members with their Spanish names. Why did you choose to do that?

Cyn Vargas

It shows the first generation sort of in between—we’re speaking two languages to one another at once, right—Spanish and English in one household at the same time. I think part of it, too, is we lose a little bit of the culture sometimes as the generations move forward, it could be just a little bit of us holding on to where we came from. I’ve always felt when I’ve gone back to El Salvador or Guatemala, I’m American, I am not from there. I dress American, even with my Spanish, I sound American, I have the accent.

When I’m here, I am looked at like I don’t know if people know I’m American or not. I’ve been asked where I’m from, where my accent is from, and I’m not American enough. So the only time I’m both really genuinely is at home—or on a plane (laughs). That’s it. And so I feel like I don’t even really think I thought about [Itzel calling her parents Mom and Dad], it was just something that was natural to me.

Maybe it’s also just a little bit of holding on, like when you don’t want the party to end, but it’s sort of over. So you pick up some of the streamers off the floor so you can remember the party and carry it with you. It’s something like that, I think. First generation, it’s a weird place, and it can be a lovely place, and it can be a challenging place, especially for kids.

Ruby Rosenthal

The novella takes place in past tense, but your title is in present tense. I was curious if this had the implication that, after the novella ends, things don’t really change in Itzel’s life.

Cyn Vargas

I would say nothing’s ever the same really means it’s never going to be the same as it was between this front and back cover. This is how it was, and after that, it’s not the same. Everything has to change at some point, right? Everything in life is chapters, and especially adolescence, when you learn that your parents are not what you thought they were. It’s not going to be the same.

I think even if we look at relationships, when you start with someone in the beginning, right, they call it the honeymoon phase. And then that changes—nothing is the same, because hopefully it evolves into something else, not because it ends. I wanted to show a story of [evolution], but from a 13-year-old’s point of view, who thought her world was never going to change. [But also] because, you know, good stories always continue beyond the last page, that’s why you’re sad when it ends.

FICTION

Nothing’s Ever the Same

by Cyn Vargas

Tortoise Books

Published May 14th, 2024

Ruby Rosenthal is a writer based in Chicago, holding a BA in international studies from Stetson University, and an MFA in creative writing from Hollins University. Now CHIRB's social media manager, she was previously Narratively’s Editorial & Development Assistant and an intern at StoryStudio Chicago. A nominee for AWP’s Intro Journals Project, Ruby was a finalist for Whitefish Review’s Montana Prize for Humor (2024) and her work has been published or forthcoming in HerStry, Defenestration, Hypertext Magazine, and elsewhere.