I met Gabriel Carle at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus, around 2014. If memory serves, we were both enrolled in the same seminar on contemporary Puerto Rican literature. I read their stories soon after. Tactile, sweaty, fast, vulgar, and free, these orbited the lives of queer kids and college students living on the island. Reconnecting with Carle a decade later by way of their English-language debut, Bad Seed, is a great opportunity to learn how much their writing has evolved. Translated from the Spanish by Heather Houde, this newly expanded edition still vibrates with the heat and absurdity of life in the Caribbean, but the edges of its world are now filled in with details that hint at the ever-changing consequences of the island’s colonial relationship to the US, a never-ending trail of misery and shit, aggravated by natural disaster and imposed austerity. Luckily, Carle’s characters are still busy attending class, barely getting by, writing, going to the beach, getting high off their minds, falling in love (or lust), struggling with dysphoria, and testing the boundaries of their gender identity in such an ecstatic way that the collection also points towards a truly bilingual future for writers from the island, one in which they can express the complex identities at play in Spanish, English, and Spanglish to reach a whole new audience.

Iván Pérez

I think I recognize some of the stories from reading your stuff way back when, during that literature seminar we took together. Did you write the rest of the stories in that version soon after? Or more to the point, how did this collection of short stories come together?

Gabriel Carle

It’s funny that you remember that, because those creative writing courses were so formative, and between the classes I took and the friends I made, those years I remember as very hopeful—o sea, a pesar de las crisis de todo tipo, y justo antes de los huracanes, pero para entonces se escribía con más esperanza. Now I’m not so sure. But the stories in the collection were written throughout all of my writing seminars at UPR from 2012-16, mis primeros cuatro años en Río Piedras. They grew out of courses with Mayra Santos Febres, Guillermo Rebollo Gil, Rosa Guzmán, Elidio Latorre Lagares, plus dancing to house with my friends and the controlled substances we ran through that brought us together. Lo mío era la autoficción, so I see myself in every protagonist, on every page, pero esa persona no soy yo, es mi sombra. The versions of me that I thought I was becoming, for good or bad. After a few years and the hurricanes passed, I realized that I had a whole collection here, a series of freeze frames or still lifes from the end of an era. My college friends that read it have thanked me because they see themselves or their memories from that time come to life, if you will, even though it’s a book. By the time I was in NYC working on my MFA, Heather Houde had started translating Mala leche and even shopped it around until her hard work paid off and now it’s almost out! But two of the stories in Bad Seed I wrote originally in English, so they’re not translations. A ver si pegan. I decided to add them for page count but also to try out how my emotions and feelings would sound in my own English, y enfatizo cómo sonaría en mi inglés porque pienso que todo cuento debería poder aguantar ser leído en voz alta.

Iván Pérez

The protagonists of the first two stories are both young, cis-gender boys, in seemingly opposite ends of pubescent self-discovery. The former spends the last weeks of summer, before the beginning of a new school year, indulging in as much television, gay porn, and video games as possible, while the latter is feeling like he would be better off if he had been born straight, had a woman’s body, or was HIV positive. Read in tandem they suggest the potential ecstasy or despair of sexual awakenings. How do these two stories set up the rest of Bad Seed?

Gabriel Carle

Me encanta conocer las interpretaciones de las personas de estos cuentos, because those two especially are so personal and so autobiographical that I’m like, “Oh, thanks, Iván, I like that, I should take that to my therapist!” Énigüeis, I wanted a slightly chronological beginning in terms of age or development—from teenager to college student. I wrote “Luisito” when I was 19, suicidal after a horrible first-year experience at Penn State, begging Mayra at Río Piedras for absolution, and her class offered me the space I needed. I also was so depressed that I had to go back to another even more depressed phase in my life, when I was 14 and going through so many hormonal changes that my entire body as well as my social environment turned into a living nightmare. Dysphoria is real, and I envy teenagers today that, if they’re blessed enough to live in a more progressive state, they might have access to hormone blockers and not go through all the torments my peers and I put ourselves through. In a way, I go back to these memories through fiction to change the outcomes or to change the words people said or to offer a seemingly endless portion of my life a semblance of catharsis through dénouement. Sometimes navel-gazing has some merit, on rare occasions, and I believe the rest of the book stays close to that impulse.

Iván Pérez

At first blush, that second story has an especially bleak ending, since Luisito, the protagonist, moves from fantasizing about his life as a woman to hoping for the living death of a heroin addict. Why does Luisito’s desire for self-annihilation take shape in parallel with descriptions of the crumbling infrastructure of his surroundings?

Gabriel Carle

I think that crumbling infrastructure is part and parcel of the Caribbean experience. Al menos en Puerto Rico, y especialmente en San Juan. For those of us born in the neoliberal ’90s, nunca vimos un mejor Puerto Rico. Everything got worse every year, the blackouts, the storms, the utility bills, the price of food. My grandparents spent most of their adult lives in San Juan, and they used to talk about the trolley or taking public transport, y me imagino lo vivo que habrá sido la capital en aquel entonces, o el Paseo de Diego y los comercios del área. But in my memory, Río Piedras progressively became a ghost town, and then old houses would be bulldozed and left vacant forever, más los edificios abandonados y los estorbos públicos en cada esquina coupled with the increase in deambulantes y drogadictos. So I have a very specific San Juan as a backdrop for the static in my brain—mucho polvo, reja enmohecida, jóvenes perdidos en el vicio, wrecked buildings occupied by whomever . . . all of these elements came together in real life and in my perception of the world. So “Luisito” reaches towards those spaces—the perceived end of the road, en donde todes podemos caer.

Iván Pérez

The rest of Bad Seed displays a similar commitment to bringing readers into its stories’ different settings. Why does the University of Puerto Rico and its environs inform so much of the collection?

Gabriel Carle

¿¡Cómo no hacerlo de la IUPI!? Just like those creative writing courses, the University of Puerto Rico and my hometown of Río Piedras are my happy place—y lo digo sin ironía, en Río me siento en casa porque lo es. It was cheap back then, too—I never paid more than $300 for a room during my six years as an undergrad, I can’t imagine prices now. La IUPI fue donde me conocí a fondo por primera vez, donde me abrí a ser descubierte. I found so much life, so much drama, in my hometown during college that I had no choice but to celebrate it—the drugs and the long nights, despite the criminality and the danger, the sex and the parties, despite the fear and the economy . . . I wanted my undergrad to last forever, because on top of all of the self-discovery, I was learning my own country’s and my city’s history, while discovering the wild ways concrete reality could bend to my will through blank sheets of paper. The potentiality I found burgeoning from the center of all that precarity taught me that even dereliction, whether through depression or irony, can sprout many great things, and my own survival, as well as the many iterations of this book, were some of them.

Iván Pérez

To pivot slightly, let me ask you about influences and inspirations. While reading, I couldn’t help but think of your style in context with the work of writers like Pedro Lemebel, Andres Caicedo, and Manuel Ramos Otero, among others. The last two are even cited in the collection. What role does artistic influence or inspiration play in your writing practice? Are there any influences you feel are more front of mind when you work on newer stuff? Which influences have receded to the background these days, or better yet, lie deep underground?

Gabriel Carle

Pastiches are some of the most effective creative writing exercises I know. “En el bathhouse” es un pastiche de uno de mis cuentos favoritos de Ramos Otero, “Hollywood memorabilia”. I believe in diagramming sentences and mad-libbing my way through my favorite stories until I can see what works with my tongue and what doesn’t, what rhythms I can take for myself and what new syntactic structures excite me. I’ll admit it’s very nitpicky stuff, but on a content level, I rarely read muggles—meaning males or straights. Mis mayores inspiraciones son cuentistas que narran historias increíbles con un formalismo apabullante—Mayra Santos Febres, “Oso blanco”; Alice Munro, “Material”; Janette Becerra, “Visitabas puntualmente el consultorio”; Diamela Eltit (my MFA thesis director), Los vigilantes; Lydia Davis, any of her stories; Samanta Schweblin, Pájaros en la boca. I was always obsessed with short story collections, porque se podían leer a cuentagotas y porque había una larga y muy rica tradición en Puerto Rico. That said, I always read in English as much as in Spanish, but I’m always looking for formal experimentation of the short story, in either language, that’s what moves me and my writing. This also feeds into my process—si estoy escribiendo, tengo que estar leyendo algo también, probably entirely unrelated to the theme I’m then concentrating on, pero algo que me siga dando leña al fuego, some inspiration on a lexical or a syntactical or a rhythmic level.

Iván Pérez

Some of these stories are funny or psychedelic in really unexpected ways. What role does genre play in stories like “Casablanca Kush” and “Devilwork”? What about humor, comedy, or goce?

Gabriel Carle

I credit much of my imagination to the many creative writing workshops I took with author Eïric Durandal Stormcrow in Puerto Rico. Tomé sus talleres de memoria, fantasía, ciencia ficción, and others, on Saturdays for many years, and I was so broke that he wouldn’t even charge me, and I believe he also enjoyed watching my brain soar. I realized through working with him that writing was, on one side, meant to be fun for me; and on the other, it was meant to be experimental, or unexpected, or weird in many ways. I was never totally convinced with realism or “high” literature. Literature was supposed to be like being high—hurling readers towards a different dimension, exploring the limits of glitches in reality. En cuanto a goce, pues mira, nunca sé que mis cuentos dan risa hasta que los leo en voz alta y la gente se ríe. It all seems so serious in my head until someone tells me how much they enjoyed living the traumas of my late adolescence vicariously. I think irony well-versed and well-used serves to highlight the undersides of narratives and offers alternatives to many one-sided stories. En todo caso, this collection had a specific audience in mind—my queer college friends—and my aim for some stories was to give them almost a transcript of a wild story I wanted to reminisce with them . . . if that makes sense. Es tan gozoso contar el chisme como recibirlo, más aún si se exagera.

Iván Pérez

You recently became a part of Puerto Rico’s diaspora. Do you hope the island’s diaspora finds these stories? What do you think (or hope) they will take away from your version of Puerto Rico?

Gabriel Carle

Of course I want all my Boris to read me! I feel that most of us were raised fascist and sheltered into oblivion, and going through queer adolescence was horrible by myself. Books offered me an outlet like never before, justo cuando más lo necesitaba en mi vida, but I was always looking for stories that spoke to me on a personal, spiritual level. Queerness was not legible to me on the island, but I blame my pro-statehood mother and grandparents. That said, queerness spoke through my body towards everybody else—and no matter how delulu or conservative or violent or repressive the state or parental units could be to queens like me, they could not stop my boogie. I want Boricuas the world over to recognize those queer family and community members, feel empathy and sympathize with them. I find that queer community can be family, that they have filled in that absence when my actual family was unable to provide me the emotional support I needed. I find hope in that, and my wish is that our larger communities can feel warm at the thought that, as a community, islander or not, como Boricuas, nos tenemos.

Iván Pérez

Finally, what is next for you? You are also a researcher. Will your next book be for a specialized or scholarly audience? Or are there plans for more trade fiction?

Gabriel Carle

My first novel, Folly, comes out in Puerto Rico this summer with Ediciones Alayubia. It’s about an islander isolated in New York after the hurricanes, after having lost everything, and the neighbor about whom they’re obsessed and can’t shake off like a short story you can’t or won’t finish. Lo escribí para la maestría, but the pandemic threw everything in the air. I’m currently writing my dissertation on poetry and culture after hurricanes in the Caribbean—disaster poetics, poetics of memory, decolonial environmental thought, etc. Deséame éxito.

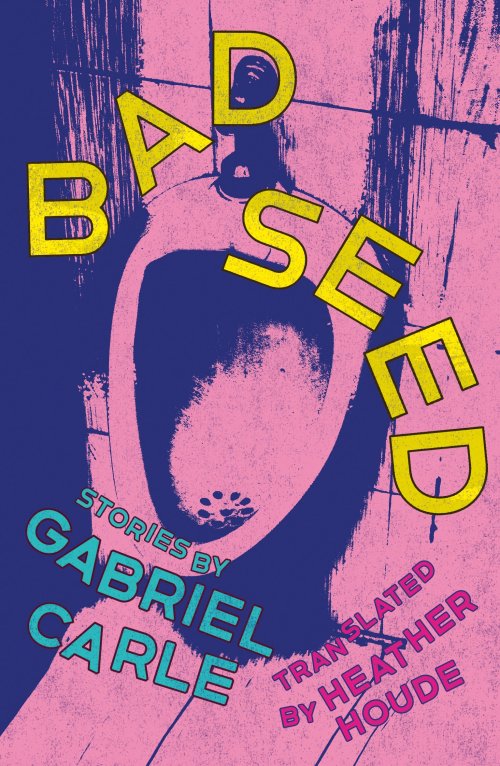

FICTION

Bad Seed

By Gabriel Carle

Translated from the Spanish by Heather Houde

Feminist Press

Published May 7, 2024

Iván Pérez is originally from San Juan, Puerto Rico, but now lives in Chicago. He is a poet, comics studies scholar, and the acquisitions coordinator for Northwestern University Press. He co-edited "Un nuevo pulmón : antología del porvenir" (La secta de los perros, 2015); his first chapbook, “Para restarse” (Editorial Disonante), was published in 2018; and his doctoral dissertation was successfully defended in 2022.