Something comical lies buried in William Faulkner’s seminal work As I Lay Dying. As the coffin of Addie Bundren jostles across troubled waters, sliding inside the physicality of the “grave and hearse”—a phrase adopted by 21st century band Houndmouth in “Sedona”—the novel shifts the physicality of grief. From young Vardaman to Cash Bundren, the narrative of grief available to the reader barricades each character, both caught in their own first-person experience.

Chloe Michelle Howarth’s Heap Earth Upon It adopts a similar narrative style to Faulkner’s structure. Whereas As I Lay Dying offers the perspective of the deceased and those left to carry the coffin, Heap Earth Upon It offers the O’Leary clan as individuals who hide whomever they left in Kilmarra.

Elements of traditional gothic literature peak through in Chloe Michelle Howarth’s sophomore work, which follows the O’Leary’s as they descend in Ballycrea in a donkey drawn cart, even though cars were invented. Newcomers to town, the three siblings, Jack, Anna, and Tom inhabit first person narration; Anna and Jack focalize a ‘you’ in their thoughts of a character left behind Kilmarra, unnamed until later in the plot. Tom, the family’s patriarch, in the absence of their father shepherds the siblings towards his decisions; Jack is affable like Soda Pop in the Outsiders, except we rarely see this put to use as he wades through grief; Anna, seems to resent her role as stand in matriarch for their half-sibling Peggy—and her gendered pigeon hole becomes the source of Tom’s later dishonesty.

However, compared to As I Lay Dying where Vardaman’s childlike and philosophical proclamation shines through in declaring his mother a fish, the youngest sibling, Peggy, sharing a different father from the rest, populates the pages of other characters without her own retelling. Instead, we are offered Betty, initially postured as the “nosy neighbor” but instead adopting the character traits of the Kinsellas in Claire Kegan’s Foster—a narrative inverse.

The character traits of Tom, the eldest, appear in the descent to Ballycrea with his brash laughter in new crowds, eager to please and find work. As the male head of household, Tom serves as both the financial provider and the architect of their new life, from forcing friendships with Betty and John Nevan to a joviality in establishing a way the O’Leary’s are perceived. Anything that threatens the sustained people-pleasing arc, in interpersonal and group dynamics, startles Tom to clear the path for a new reputation, which he believes will benefit his siblings, bolstering them as a bereaved unit—arguably true for all except one family member.

If birth order were defining character traits, Jack, the younger son, gleams golden with handsomeness and ease in turning a wan smile into a charming grin. The dynamic of order imposed and ‘come as it may’ could create an eruption of conflict between the two men; however, Jack’s subdued state of grief instead engulfs him in waves of guilt for using his charms to win over Teresa rather than create physical conflict. While Tom attempts to win invitations and goodwill, Jack watches from the bench, sitting on the knowledge that, for him, this would all be so much easier—an underlying tension between the brothers.

Jack and Tom pursue the admiration of Ballycrea’s inhabitants in separate windows. Tom spends time watching The Late Late Show with Betty and John after a day of manual labor, inserting himself in their marital domestic world, while Jack polishing glasses at the bar keeps his eyes on Teresa.

Anna and Betty serve as the most startling literary pair for all of the one-on-one time spent with each other. Peggy’s oscillation between the two homes without providing a perspective serves as a reason, in addition to Tom’s persistence, for the two to initially unite. The shape of Anna’s narration glazes inwards further, removing her from the actions unfolding and instead bending her own unique reality, whether this be through pilfering Betty’s blue scarf to descending into obsession between the “you,” later revealed, and Betty. Similar to Jack, her grief spans into the guilt of pursuing a new object of attention because in their narrative these people are objectified for the place they hold in the narrator’s head.

What’s unique about Anna is the weight of her obsession with Betty, a surmounting romantic tension in her eyes which eventually stalks the Nevan’s house and seems to provide further evidence of reciprocal feelings. In lieu of Peggy rounding out the narrative to include only the O’Leary family as the youngest child, Betty’s narration eventually becomes crystalline as water, providing a dose of reality to Anna’s recollection of events. Compared to Anna’s lust, Betty is pervaded by fear as Anna deems herself more romantic.

The stylistic shift from American Southern gothic to Irish gothic pervades Heap Earth Upon It, setting both plots into motion with a metaphorical hearse weighted and dated. Chloe Michelle Howarth’s take on the gothic provides a refreshing perspective on Faulkner’s novel by providing only four narrators yet anchoring this sense of staying and leaving into the dynamic of one, Anna, and her relationship to the external world. Anna is self-aware of her place in the family but lacks understanding in the face of paramours, drawing the reader into her deeply intrinsic and papered over perspective on the relationship dynamics spread throughout the novel.

FICTION

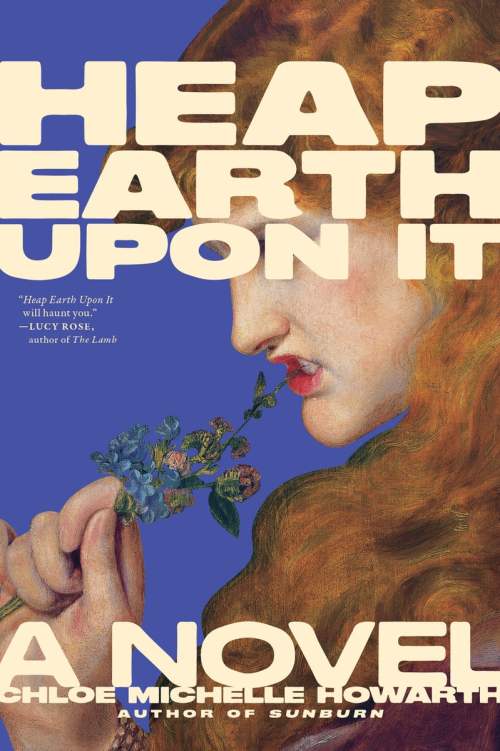

Heap Earth Upon It

By Chloe Michelle Howarth

Melville House

Published on February 3, 2026

Mia Rhee received a BA from Northwestern University where she studied Creative Writing. Her work has appeared in Remake and The Chicago Review of Books.