The Hitch follows Rose Cutler, a prickly and dogmatic woman living in the Chicago suburbs. She operates an artisanal yogurt company and is finally getting to spend a whole week with her six-year-old nephew, Nathan, while his parents are on vacation.

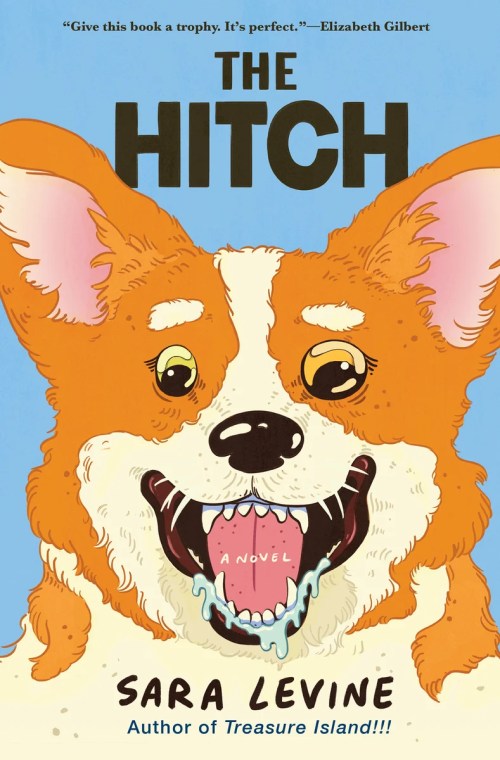

When her Newfoundland accidentally kills a corgi at the park, the corgi’s soul takes up residence in Nathan’s body. How does one exorcise a corgi from a little boy in less than a week?

Through this comedy of errors, Sara Levine issues a profound warning about nitpicking and the price of maintaining a rigid worldview. I had the opportunity to interview Sara about her novel. We discussed dogs, emotional detachment, and making the other person feel wrong when you feel wrong.

Anson Tong

What inspired the inciting event of the novel (the narrator’s dog inadvertently killing a corgi)? Were there ever other dogs or souls considered? A lot of people don’t like when dogs die in media (there’s even https://www.doesthedogdie.com/ so it can be checked in advance), so I’m wondering if it felt like a risk when you were writing to make a dog death such a central plot point.

Sara Levine

Yes, I knew it was a risk. But I like a good risk when it comes to fiction. Rose thinks she knows the right way to do everything, including training her Newfoundland. So the story needed a mistake of this magnitude in order for Rose to unravel her tightly held assumptions. As for where the idea came from, it’s hard to say. I do know someone who backed out of his driveway and accidentally killed their neighbor’s Westie. I learned about the accident secondhand but could never bring myself to ask about it. As you’d expect, I wondered how he apologized to the neighbors and how he learned to live with the awful fact. But ideas come from more than one place, I think. So another explanation is that in my novel Treasure Island!!! a parrot meets an untimely death, and finding so many readers furious about that fact, I decided to up the ante.

I never considered any dog but a corgi. I wanted a small adorable dog whom most people would be able to picture. A breed that Rose would despise for the very reasons other people love it.

Anson Tong

Rose is a charmingly neurotic, pedantic narrator. She’s a bit of an unlikable female character, less in the vein of extreme transgression and more that she is curmudgeonly and an older, unmarried, childless woman. How did you approach crafting an abrasive character that readers have to want to keep following along for the story?

Sara Levine

Yes, Rose is thorny. I think of her as deeply out of touch with the tumult inside of her. Her opinions aren’t always wrong, but she’s unaware of how she marshals them to avoid her own inner world. It’s easier to feel angry or self-righteous than vulnerable or sad, so she rails at [her brother] Victor about the history of pancakes rather than admit she feels abandoned by him. Writing her, I often thought about Blaise Pascal’s Pensées: “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

Now if you were to meet Rose in real life, you might go running. But you aren’t meeting her in real life; you’re meeting her on the page, where her energy is controlled and given shape through sentences and narrative design. I hope the pacing and energy of the plot pull the readers along. I also hope people enjoy the act of detecting the emotional confusion that lurks beneath Rose’s well-groomed surface.

Anson Tong

Veganism and animal ethics are a significant hill that Rose is prepared to die on. Ultimately, this is one of those things where it’s not that she is substance-wise incorrect, but her impositions on other people cause conflict and she’s often the odd one out. Oftentimes people with the morally righteous stance have been cast as nags, downers, and annoyances for disrupting the status quo. How do you think about navigating that tension between being right and being overly critical?

Sara Levine

You know, I thought a lot about where Rose flares up with big opinions. Her retreats to the moral high ground are never accidental. It interested me to think about how much Rose needed to be right, and why she needed to be right. The Hitch to me is very much about boundaries! I mean, obviously, the corgi wanders out of bounds. But Rose has serious trouble staying in her lane. She tries to dictate other people’s actions as well as their thoughts. Often she doesn’t even know she’s being critical. She just thinks she’s done the research and read the studies. I thought there was a lot of comedy in that, but I also resonate with her problem. I think all humans do this—just not to the same extent. You don’t want to feel wrong, so you make the other person wrong. You defend your little corner.

Anson Tong

Rose had to raise her younger brother Victor after their parents died, and then she became quite wealthy off her artisanal yogurt business. She’s conventionally been successful, done the “right” thing, and really upheld the mantle of eldest daughter. Yet she’s totally cut off from her own feelings and finds herself raucously unhappy deep down. Can you talk a little bit about this discordance you’re getting at, that many people go years (and maybe their whole lives) operating inside of?

Sara Levine

Well, I think you said it beautifully: she’s “raucously unhappy.” And I think she learned to not feel her feelings because, as you say, her parents died young, and she needed to forget about her grief in order to survive. When viewed externally, she’s a success—a fighter, a striver, the type of woman who might be profiled in a business magazine. When the story begins, she doesn’t even know she’s unhappy. She thinks if her brother and his family would spend more time with her, life would be great. But the fact that they don’t want to do Sunday night dinners anymore is their fault. “Are we going to find out what happened to Rose?” my editor asked me. In response, I looked for an opportunity to state more clearly what happened and yet still stay true to the book’s code of compression. I ended up adding a tiny bit more about the family background (cold and joyless parents), but could not bring myself to abandon the iceberg method. Because, as you’ve said, Rose doesn’t know what happened to her. Until she gets to therapy, she probably won’t ever know.

Anson Tong

A number of different relationships to dogs are portrayed in The Hitch. They’re burdens, threats, companions, victims, witnesses, infinite intelligences. Rose opines that, “Dogs don’t supply unconditional love. But they let you love them, even ravish them, without any humiliating remarks—and that’s a service.” What is it about the risk of “humiliating remarks” that makes it easier for people to connect with animals rather than the people around them?

Sara Levine

People always say dogs provide unconditional love, but I had a beloved dog who walked—no, ran—out of the room whenever I began crying. So I do wonder how often humans project “unconditional love” onto their pets. But yes, dogs don’t make humiliating remarks, and for someone with intimacy issues, that’s a real gift. Dogs might shake off your caress, but they’re not going to complain that your breath smells, or accuse you of being a poor listener. And dogs don’t wait for weeks to tell you about their feelings. They drop their tails when they’re scared; they run in happy circles when they’re joyous. If you’ve ever been knocked off balance by a friend who tells you they’ve been simmering about something you did last week, or last year, you’ll understand why dogs can seem like straight shooters. There’s no risk of dishonesty. So if you’re traumatized from childhood or simply baffled by the complexity of human relations, you might find solace in the company of dogs. But I don’t romanticize dogs or ever want to sentimentalize the bond between dogs and people. Arguably Rose “has” a dog in the same way she “has” mid-century ceramics or an antique bed. She misses Walter’s cues in the park. She thinks he “suddenly” pounced, whereas more likely there was a ladder of aggression, and she missed his signs of stress. By the novel’s end, I hope she’s beginning to see Walter more clearly. I like to think she’ll slowly, and inefficiently, grow to love him as a separate being—not just a prize possession who fails to criticize her!

Anson Tong

Rose experiences a bit of an epiphany about the limits of her aforementioned narrow perspective on life. Do you have any advice or musings for people who have been treating the “vast, inexplicable soup” of the universe “like a bouillon cube”?

Sara Levine

I don’t want to be like Rose and offer unsolicited advice! There are many paths to spiritual awareness, and I trust everyone to find their own way.

Fiction

The Hitch

By Sara Levine

Roxane Gay Books

Published on January 13, 2026

Anson Tong (she/her) is a writer, photographer, and behavioral scientist based in Chicago. Her work has appeared in Chicago Review of Books, Chicago Reader, The Brooklyn Rail, Joysauce, The Rumpus, The Millions, and Stanford Social Innovation Review. She writes a newsletter called Third Thing (thirdthing.substack.com), which has no theme and more than three things. She was a 2023 Zenith Cooperative mentee. You can find her website (and her Bluesky!) at ansonjtong.com.