While Chicago may be known as the Windy City, the city is really defined by Lake Michigan, the seemingly endless body of water. It’s the city’s pride and joy, but as Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski, Professor Emeritus at Loyola University Chicago, argues in his new book, it’s also part of the impetus of Chicago’s rise as a metropolis.

Dr. Karamanski’s Great Lake: An Unnatural History of Lake Michigan gives a wide-sweeping look at Lake Michigan, starting in prehistoric times when the lake was being created by the glaciers through to the present day. Each chapter is chronological and focuses on how humans have used the lake. As a real treat, he explores Chicago’s lesser-known maritime history, which really is the secret to Chicago’s progress (and the rise and fall of Gary, Indiana).

This book is an important read because, as Karamanski explains, while Lake Michigan is the reason for Chicago’s success, Chicago’s ascendancy (along with other developments around the lake) threatens the vitality of the fresh water lake.

We had a chance to talk with Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski about Great Lake: An Unnatural History of Lake Michigan via Zoom.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Elisa Shoenberger

Why is this book so important? Why is it so important to talk about the natural history of Lake Michigan?

Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski

Because it’s endangered. It’s been endangered somewhere since 1673 when the market arrived on the shores of Lake Michigan and began to change people’s relationship with nature. There’s some very special things that are happening now that make it all the more important. Global warming is one of those. We’re essentially undertaking a global wide science experiment to see what would happen if we went ahead and dumped more CO₂ into the atmosphere and raised global temperatures.

We don’t know what’s going to happen there, and I think particularly those of us in the region need to be especially vigilant in monitoring what’s happening to this magnificent resource that we have, a resource that so defines our region of the country, the whole Great Lakes system.

I grew up in the bungalow belt in Chicago, and years would go by where we wouldn’t see Lake Michigan. The water that came out of the tap and went into the showers was something that came from the City of Chicago. There was no comprehension that it came from Lake Michigan. I think that’s true of literally millions of people in the metro area whose lives are essentially divorced from the lake, except it’s vital to their daily survival.

When things are out of sight, they tend to be out of mind. And so I think that the leaders of a place like Chicago, a place like Milwaukee, Muskegon, the states of Michigan and Wisconsin, need to be vigilant in helping people understand so they can appreciate this fantastic resource.

Elisa Shoenberger

Where did this idea of the book come from?

Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski

At Loyola University Chicago, I have an office in the Crown Humanities Center, and it’s located right on Lake Michigan. My particular office faced the lake, which was 20 yards from the water. Every morning I would get to campus early, because I had a commute from a long distance, and I’d see the sun rise over the lake. It was just spectacular in wintertime with all the different shapes and variations of ice and snow on the water.

I’d been working doing environmental history-type projects since the 1980s and a number of them had touched on Lake Michigan. I did some work for the National Park Service on the history of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore and working with people at other parks like Indiana Dunes.

Then also, since 1980, I had been working with a group of people who wanted to have a Chicago Maritime Museum. We finally got the museum in 2013, which is at the Bridgeport Art Center. It kind of forced me to become a maritime historian, which if you’re doing Chicago maritime history, then Lake Michigan is ground zero. It was both a professional and personal connection to the lake over the years.

Elisa Shoenberger

Why does the book have the subtitle “An Unnatural History of Lake Michigan”?

Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski

I worked for eight years at The Field Museum before I was in the faculty. It’s “The Field Museum of Natural History.” But there was no exhibit about Lake Michigan in the museum, even though it sits on its shores. It had collections of insects, plants, invertebrates and mammals, but all of that was natural history.

I was writing about industrial pollution, about the development of navigational facilities on the lake, and about the rise of urban centers. I saw all the stuff not covered at that museum. It was unnatural. It was the things that we have done to the lake. That’s basically the theme of the book: what we have done to the lake, and how the lake has shaped us.

Elisa Shoenberger

What surprised you most when working on the book?

Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski

Growing up on the south side of Chicago, I always knew about the steel mills being there. I was surprised how much the steel mills completely changed the whole lakeshore from where the Calumet River comes into Lake Michigan, then all the way along the Indiana shore. It was amazing to me how much of that had changed in my lifetime.

United States Steel Corporation South Works would deposit clinkers and other industrial debris every year. That expanded and expanded and expanded the lakeshore that they controlled. They filled in so much of the marshlands around Lake Calumet, and there used to be all these other lakes in northern Indiana until they got filled in. The sand mining took down vast dunes, and that sand mining is still going on.

I was surprised how changes to the geography of the shoreline have cascadingly negative impacts every time we get a high water phase. High water phases and low water phases are natural on Lake Michigan, but when the high water comes, there’s this panic over people losing their homes and all that. Northwestern University is one of the classic examples that built a humongous landfill for their campus. It is a beautiful addition, but it has catastrophic consequences for people who have homes on the Indiana and Michigan shores. All those little things have happened in my lifetime.

Elisa Shoenberger

In your chapter on invasive species, I thought it was really fascinating, because not only do you talk about non-human exotic animals in the water, you talk about the arrival of non-Indigenous people to the lake as well.

Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski

You have to go back and look at the geological evolution of the lake. The Rocky Mountains were there for a million years before there were any people who ever walked upon them or climbed them; the deserts in the American West were there for a million years before a single human footprint set upon them. But that’s not true of Lake Michigan. Because when it was just a meltwater pond of the glaciers, there were people coming into this region, living along its shores.

Over thousands of years, the lake became bigger than it is today, and became much smaller than it is today. Native people were living on its shores. Fifty to 70 miles out into the lake today, there would have been Indian villages out there. So I regard the Native population as Indigenous because they were formed part of that natural history of Lake Michigan.

Of course, they’re like every creature in the world. They live by exploiting their environment and by exploiting it, they change it but it was part of that natural system that they weren’t upsetting any major balances.

When European Americans came in, they immediately began disruptive changes to the landscape. They made alterations to what the lake had been, and that is the marker of our society. It’s a reflection of our values. Native Americans had a spiritual, ethical relationship with nature, whereas we have an ecological relationship with nature, in which, through science, we think we understand the natural processes, and then we seek to manipulate them to our advantage. It’s that desire to manipulate nature to our advantage that’s at the heart of everything that followed from 1673 on.

The big change of course is navigational improvements. We perceived this incredible, vast water landscape as an inland sea, and we wanted to use it in the same way that the ocean is used. That was our big argument to get the Feds to come in and help us transform the shoreline with harbors and lighthouses and other navigational aids so that we could put all these ships out there. Sailing ships for a while were the covered wagons of the Great Lakes frontier, bringing people in. Those navigational improvements are what first let the invasive species into the lake.

Elisa Shoenberger

In the book, you talk about how you know every step causes challenges in a different way. It’s like a vicious cycle. Even treating the lake as an amenity isn’t consequence free. More people want to come, more resources are needed. It’s where the thing that’s being appreciated is being destroyed by its appreciation. Are you hopeful?

Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski

Am I optimistic? Not a heck of a lot, but I’m not totally pessimistic either. The environmental improvements that were made in the wake of the 1972 Clean Water Act thanks to the actions of groups like the Lake Michigan Federation made the lake a lot cleaner.

There was a lot of pollution that was prevented from getting into the lake, and the millions and millions of dollars that the federal government contributed to help cities like Chicago and Milwaukee and other places stop having their sewers going directly into the lake. This made a difference. In the 1990s, people would say, “we saved the Great Lakes.”

Then all of a sudden, we saw these other changes that had happened out of sight, like the ballast water bringing in these invasive species from the Black Sea. They have totally transformed Lake Michigan in a way that no one could have imagined. It was again an unintended consequence, but we found legislative actions and scientific interventions, particularly in the example of repressing the sea lampreys, to make improvements. While we have the ability to not foresee all the consequences of our actions, we also have the ability to make rational interventions for the better.

Elisa Shoenberger

Thanks so much for speaking with me. Is there anything else you want me to know?

Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski

I think one of the things that struck me—I did not do this as much as I wanted to or as I’d hoped to—was to get a sense of how Lake Michigan affects our imagination. I have some quotes from people like architect Louis Sullivan, poet Carl Sandburg, and writer Willa Cather. It just kept coming up that there was this sense that the lake was something that would give you a sense of freedom.

Ben Hecht also had an interesting quote where he would see the lake every day taking the train into work as a journalist in Chicago. He basically said that looking at that grand vastness of the lake, your everyday cares would kind of vanish. But it then gets you thinking about something else. He says that sometimes it would actually make you sad because looking at this vastness was a reminder that life has so many more possibilities than we take advantage of. That’s something that I set out to try to capture, and didn’t succeed as well as I liked. I have been unresolved in understanding how the lake fits into my life.

NONFICTION

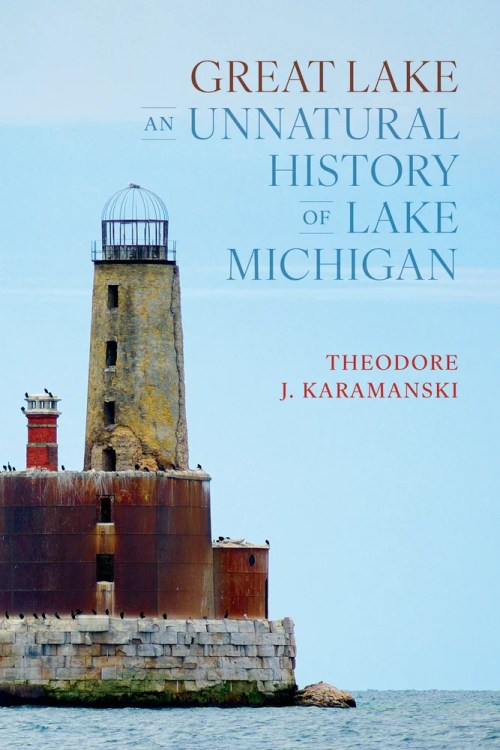

Great Lake: An Unnatural History of Lake Michigan

by Dr. Theodore Karamanski

University of Michigan Regional

Published on January 6, 2026

Elisa Shoenberger is a freelance writer and journalist in Chicago. She also has written for the Boston Globe, Huffington Post, WIRED Magazine, Slate, and others. She writes regularly for Book Riot, Murder & Mayhem, Library Journal, and Cheese Professor. She’s obsessed with dogsledding, murder mysteries and cheese.