IIn Chicago, you can feel the weight of history everywhere. The architecture bears the marks of a great fire. The city meets at the intersection of an ancient glacial lake and a river that once flowed into it, and now flows away. And listen to any local in a bar, corner store, or on Bluesky and they’ll tell you the entire story of every brick, rusted piece of metal, or faded advertisement.

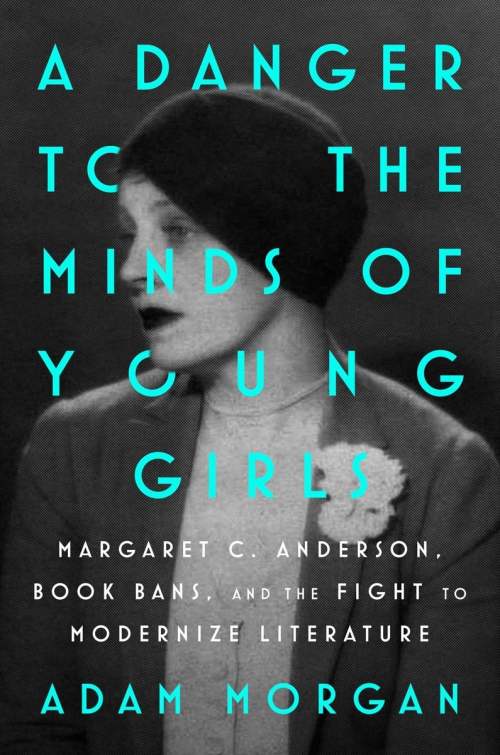

There’s something intoxicating about seeing the past wherever you go, and it’s one of the reason’s Adam Morgan’s debut biography of Chicago literary pioneer Margaret C. Anderson resonates so deeply. Anderson is best known as the founder and editor of The Little Review, which helped build the careers of modernist icons including Sherwood Anderson, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, and James Joyce. In fact, The Little Review was the first place of publication for Joyce’s Ulysses, which landed Anderson a criminal conviction for obscenity charges and ultimately laid the foundation for the book to earn its distinction as a modernist masterpiece. A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls is a wonderfully researched and consistently entertaining look at this brilliant and complicated woman. The book rightfully cements Anderson’s place in both the modernist movement and Chicago’s literary renaissance.

While Morgan has never mentioned it directly, it’s clear that Anderson and The Little Review served as a huge inspiration for the Chicago Review of Books when he founded it in 2016. This was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up: Two Editors-In-Chief of the Chicago Review of Books talking about the weight of history in the city we love and the woman who in large part built what Chicago’s literary community and culture is today.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Michael Welch

What made you first interested in researching the life of Margaret C. Anderson? What influence has she had on you as an editor, critic, and writer?

Adam Morgan

I was drawn to her initially because I was fascinated by this idea that there had been a literary renaissance in Chicago. You know, I’d grown up hearing about the Harlem Renaissance and the lost generation in Paris in the 1920s, but when I moved to Chicago, I didn’t know that the city had had its own cultural renaissance. So I was just really fascinated by that idea, and wanted to learn more about it. And as I started looking into it, she was just such a central figure. And the Fine Arts Building in particular, this was where they all were. Harriet Monroe was there, The Dial was there, Ralph Fletcher Seymour was there, Frank Lloyd Wright, the Chicago Literary Club, The Little Room, the Little Theater—that building was ground zero for all that stuff. So, yeah, I just became really fascinated with the idea that Chicago was this more European and Parisian place then, because my impression of Chicago when I moved there was that it was this tough, masculine, industrial, American city. And it is all those things too. But I was fascinated by this idea that in addition to that, it had been this “Paris on the Prairie,” a very culturally vibrant place with writers, poets, and artists who flocked to the city particularly after the World’s Fair.

Margaret’s story was such a central part of all this. But I was also inspired by her because she was just kind of a nobody from a suburb of Indianapolis. She had no connections to the publishing industry in New York or Chicago. She didn’t have a lot of money to spend. I was inspired that she wanted to do something, and she just did it. She didn’t wait for the perfect time. She didn’t wait and get all the right people involved, or wait until she had enough money to do something. She just had an idea one night, and then just immediately started making it happen.

Michael Welch

I’d love to hear more about your research process. Margaret seems like an interesting person to study because while a lot of her life and thought was published in the papers or The Little Review itself, her life was so storied and ever-changing.

Adam Morgan

It was really hard. It was extremely difficult and harder than I anticipated it being to start out with. She was not famous in her day, and so she was not the subject of a ton of scholarly work. And so if you want to learn about James Joyce or Ezra Pound or Hemingway or a lot of the other men in this book, you have a lot of secondary and tertiary sources that you can go to to learn about them. But she was not particularly famous. You’re right that a lot of her life was captured on the page, but in very ephemeral forums. For example, her magazine was basically printed on cardboard. So I did rely on her memoirs for her perspective on things and what she said at different times, and her memories of certain conversations, even though I don’t trust them word for word. She was a very unreliable narrator of her own life because she exaggerated, she elided things, and left things out. And she had a terrible sense of chronology. Like, her book just filled with anachronisms. So that was challenging. The way I approached the research process was that I just dug and dug. I dug as deep as I could into archival research at the Newberry Library, the Beinecke Library at Yale, the University of Illinois Library, and I looked into the personal correspondence of people that she wrote to and who wrote to her, and then also the out of print memoirs of anyone who may have come in contact with her. I have stacks and stacks of old memoirs, where there might be one page where this random person interacted with her, but I I pieced all that stuff together to try to build a more reliable chronology of her life.

Michael Welch

I was really interested about her intellectual evolution throughout the book, from her interest in and then disappointment with anarchism to the spiritualist movement in her later years. As a biographer, how do you approach all of these various different eras of her life and thought and place it into a narrative about who she was and what drove her?

Adam Morgan

I think the thread that ties it all together is that she definitely chased ecstasy, joy, and the feeling of discovery. Books and literature were just one venue that she did that with in her life. I structured the book into three parts with the three cities—Chicago, New York, Paris—and that somewhat mirrored what she was chasing during those different periods of her life. Like that first period in Chicago, she was just trying to escape the dullness of suburbia and become something beautiful. Then the New York period of her life was very much about using the magazine and using literature to try to find ecstasy. She did at times, but mostly she was pretty discouraged and disillusioned. She found the New York intelligentsia kind of obnoxious. And she thought people in Chicago were interesting and smarter.

Then in the third part of the book about Paris and her life in France, she was disillusioned with literature and she began chasing ecstasy via spirituality. I think that had a similarly crushing effect. Her teacher, George Gurdjieff, in my opinion was a charlatan who basically broke her down like you would break a horse. She lost her vanity and narcissism a bit from that experience, but also she lost her passion and ambitions, and she came to see herself as this silly little society girl who never really accomplished anything. It’s really sad, but as a nonfiction writer I have to follow the story where it goes, and it ends in this very kind of quiet, lonely place.

Michael Welch

By the end of her time at The Little Review you highlight that she seems to be disillusioned by the modernist movement. She even ends a section of the last issue with “MODERN ART. It has come into its own: Advertising.” Can you talk a bit about these frustrations she had and what state you see the modernist movement in by the time she closes The Little Review?

Adam Morgan

Yeah, that’s a very thoughtful, insightful question. And she wasn’t alone in feeling that way. We know Jane Heap felt even worse about it given what she wrote in that final issue. But I think a lot of the Bohemians that were in her circle at the time felt similarly. It helps to think about how they felt before World War I, and then during and after, because I think a lot of them before the war felt that their generation was going to be different. They were doing different things with art like this. They thought they had the potential to really change the world and to make it a better place, and literature could do that. Literature has the power to do that. I think it’s analogous to the first Obama era, where when he was elected there was this feeling that the future was going to be different and it would be a “post-racial” world. But for these Bohemians, when World War I happened, which at the time was the most horrific thing that had ever happened in history as far as they were concerned, there was a huge sense of loss and disillusionment that it was for nothing right, that they were wrong. Art and literature maybe could have changed a better world, but it made no difference here.

Also, when Margaret is looking back on her life and writing in the 1960s, she is this person who was just like the absolute bleeding edge of radicalism and progressivism in the 1910s but here she is in the 1960s and she finds the counterculture of that era gross and disgusting. She’s now the person who’s longing for the way things were.

Michael Welch

One of the most striking and well-known stories about her is her decision to serialize Joyce’s Ulysses and the resulting trial and obscenity charges. Obviously now Ulysses is viewed as a modernist masterpiece, but could you talk a bit about Anderson’s role in cementing its legacy?

Adam Morgan

I genuinely think Ulysses as we know it today would not exist, or at least, would have come about in a very different way than it did. When Joyce was writing it, nobody would publish it. Everyone thought it was too weird, too hard to understand, too gross, and so he couldn’t find anyone to publish it, and a lot of his other works, too, had similar issues. But Margaret loved it and published it, and then had it not had that scandal around it—around being banned and around Margaret being criminalized for it—I don’t think it would have taken off in Paris the way it did, because its forbidden nature was a big part of its allure. Also, the form of the book itself would have been different. For example, Ezra Pound wanted to cut certain things that Margaret said no to, and Joyce wound up putting grosser and weirder things in some of the latter chapters in response to some of the censorship. So there’s a very direct impact on how the book turned out, how it was published, and things like that, that led to it being the way it was. And had all these things not happened, maybe then Bennett Cerf wouldn’t have had that big trial in the 1930s to get permission to publish it at Random House, and maybe it doesn’t blow up into this classic. I think Margaret had a direct impact on the way it all happened, because she had the courage to print Ulysses as he gave it to her for the most part.

Michael Welch

I was struck by the parallels between the censorship Anderson faced and the pushes we’re seeing today to restrict our freedom to read. I also really admired how every time her work was challenged, she always pushed harder to make The Little Review a countercultural publication. What lessons do you think people in the publishing and literary world can take from the life of Margaret C. Anderson?

Adam Morgan

Yeah, great question. I mean, Margaret knew that any press is good press. But also she published, edited, wrote, created, and supported the art that was meaningful to her and that she thought was beautiful and that she thought could change the world regardless of what anyone else thought. She did not care if it was marketable or if it would sell well. She didn’t care if every one of her readers hated it. If she thought it was meaningful, she published it. And I think we need more people like that in the arts. And obviously it’s easy to say but hard to actually do. Everyone in the arts has to balance finances and career prospects with everything else. But I think something valuable in her story is just to take more chances, take more risks, take big swings. Because to me, I find failed books that take big swings much more interesting to read than popular or award-winning or best-selling books that are pretty safe.

Michael Welch

What does Anderson mean to the Chicago literary community, not only during the city’s artistic renaissance but also what it has become today?

Adam Morgan

Chicago at the time wasn’t like New York and Europe in the sense that they had an established old guard with lots of history and culture and gatekeepers and things like that. Whereas Chicago was just like this new playground where anything could happen, anything goes, anybody could do anything, anybody could be whoever they wanted to be. And I think a lot of the writers and artists who were attracted to Chicago at the time really reveled in that sense of freedom. Margaret and other women like Harriett Monroe, Anna Morgan, and Claire Laughlin really built this cultural infrastructure to support and bring these artistic weirdos together, and then gave them a platform to be published for the first time. We would not have had the Chicago Renaissance without the women who did that. And we would not have modernism as we know it today without the women who did that. Because you read The Little Review and see that’s the modernist canon, like it’s all these people who are now household names. So had she not done that, I don’t know who would have published them.

Margaret is in many ways emblematic of Chicago’s literary community today and what makes it wonderful, because she was just some kid from a small town in the Midwest who came to Chicago, found and invested in the community, and built something that she was passionate about with said community. And that’s exactly what a lot of people in Chicago’s literary community, when I was part of it, had done and wanted to do. Contrasted with New York’s literary community, which at times can have this sense of elitism and gatekeeping. Chicago’s literary community feels much more democratic and open to everyday working people and much more of a community where it lives in the bookstores and the cafes and the publications. So to me, I think that’s a pretty direct parallel between what she did then and how Chicago’s literary community works now.

NONFICTION

A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls: Margaret C. Anderson, Book Bans, and the Fight to Modernize Literature

By Adam Morgan

Atria/One Signal Publishers

Published December 9, 2025

Michael Welch is the Editor-In-Chief for the Chicago Review of Books. His work has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Scientific American, Electric Lit, Iron Horse Literary Review, North American Review, and elsewhere. He is also the editor of the anthology "On an Inland Sea: Writing the Great Lakes," forthcoming from Belt Publishing in March 2026. Find him at www.michaelbwelch.com and @MBWwelch.