In his essay, “Hamlet and His Problems,” T.S. Eliot argues that Hamlet is an “artistic failure.” “Hamlet (the man) is dominated by an emotion which is inexpressible because it is in excess of the facts as they appear,” Eliot writes. For Eliot, Shakespeare’s problem is that he has failed to find the proper “objective correlative” for Hamlet’s emotions. Emotions in art should be expressed through, as Eliot puts it, “a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of the particular emotion.” Or, like Flannery O’Connor said: “you can’t show emotion with emotion.”

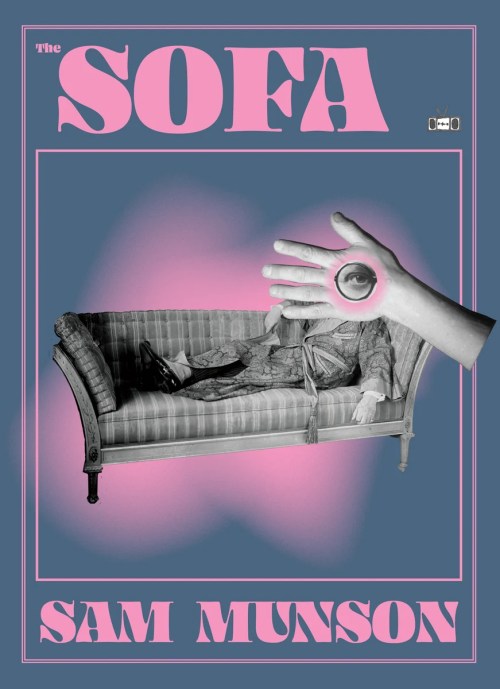

Objective correlative is the star of Sam Munson’s new novel, The Sofa, a slow burn of psychological horror, existential dread, and uncertainty. On its face, The Sofa is a domestic drama. The plot is simple, yet deceptive: A man, Mr. Montessori, living a seemingly comfortable upper middle class life, starts to experience change after returning home with his family from an afternoon at the beach. He discovers their sofa has been removed (stolen?) and replaced with a new one that has warped cushions, thick, greasy paint, and is giving off a damp smell. Under one of the cushions is a sewn in tag with the word MEERVERMESSER printed on it. The appearance of the new sofa marks the arrival of Mr. Montessori’s anxiety, dread, and growing paranoia. The new sofa is the inciting incident, it’s the occasion for the story. The physical object becomes a formula that Munson uses to explore Montessori’s change.

The sofa qua object is one of comfort, one that, yes, signifies something—identity, socioeconomic status, class, etc— about those who own it. (Is it a sofa from Ikea, or Roche Bobois? Is it a futon, a sectional…) The original sofa, a representation of benign domesticity, is then replaced with uneasiness and unreality. Objects take on a sometimes mystical and mysterious significance; they seem to exist in a different plane, taking on metaphysical questions. The longer the new sofa is in Montessori’s possession, the more agitated he becomes and the more aware that he may no longer be in control of his surroundings.

A central theme in the novel is presented in its description: “do we own our possessions—or do they own us?” The sofa, an object, becomes a subject. Mr. Montessori is no longer able to control his environment. His transformation, the slow psychological unravelling, leads to his loss of agency—everything he does is reactive because everything is being done to him.

The novel raises other philosophical questions around the idea of panpsychism—the idea that consciousness or mentality is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality. In other words, consciousness is present in all matter, not just humans, or complex organisms. Of course, this is not the same kind of mind or consciousness we associate with ourselves. The sofa starts to dictate his daily experiences, it becomes a malevolent presence, or consciousness. The downstairs bathroom seems to develop a “mind of its own.” Mr. Montessori also starts to see a hat, a bowler hat straight out of Clockwork Orange, that follows him around. He begins to occasionally catch glimpses of a mysterious figure, and whiffs of the damp smell of the sofa—all, in his mind, emanating from the sofa. In this way, the sofa becomes a tangible representation of his psychological downward spiral as Montessori questions reality while searching for the sofa’s origin.

The strange occurrence of the new sofa threatens to unravel not just Montessori’s psychic state, but also his domestic life. With the appearance of the couch comes seemingly new tensions with his wife who questions his behavior and mood. He begins lashing out at his sons to the point where the older son steps in between his younger brother and his father to prevent further conflict. Another scene takes place while Montessori is working at the cafe down the street from his home. While in the bathroom, he glimpses the recurring mysterious figure in the mirror. Out of fear, or shock, or anger he punches the mirror shattering it and bloodying his fist. When his oldest son gets a job at the same cafe, his son’s coworker looks at him with recognition. He in turn carries a sense of shame while trying to avoid her gaze.

The Sofa is a slim novel at just under 150 pages. But what Munson lacks in girth, he makes up for in atmosphere. Call The Sofa a “vibes novel,” one that benefits from the reader giving themself over to its rhythm, mood, and current of unreliability. Munson’s third-person close narrator occasionally breaks the fourth wall, adding a wink, wink, nudge, nudge sense of irony to the story. By the end, we are as unsure of reality as Montessori. But like Montessori, we keep returning to the new sofa, that objective focal point, in hopes that it might explain itself.

FICTION

The Sofa

By Sam Munson

Two Dollar Radio

Published November 11, 2025

Brock Kingsley is a writer and educator living in Fort Worth, Texas. His work has appeared in publications such as Brooklyn Rail, Paste Magazine, Tahoma Literary Review, Waxwing, and elsewhere.