Witches make the best detectives. For the last ten years I’ve been trying to solve a murder. Well, several thousand actually. It all began in the spring of 2015, sitting in the passenger seat of a good friend’s parked car in the shadow of flickering streetlights and the first wave of Black Lives Matter protests. She said, “Did you know that while a Black man is killed every 28 hours by a cop or security guard, a Black woman is killed every 21 hours by a current or former partner?” I stared at her in disbelief though she continued to look straight ahead. Turns out she was wrong. Black women are killed at a rate much higher than that. Black women are 10% of the US female population, yet they are 59% of women murdered. I now know this because what she said stuck with me and from that moment I – a woman whose second favorite genre of tv show is the lady detective in a remote, exotic locale – became something of a detective myself. Right there on the mean streets of Piscataway, New Jersey.

Confession: I never guess the killer on those shows I love. I’m only in it for the atmosphere. The messiness of her, how unlike the male detective, having custody of the kids interrupts the broodiness. Sherlock Holmes meets Big Little Lies. How the syrupy sweetness of car line interactions with passive aggressive Audi moms punctures all the gloom and are, without question, more savage than any murder. Sign. Me. Up. So, it’s not surprising that on my own detective journey among the most interesting things I discovered were other compelling lady detectives. It was surprising that they also appeared to be Black women doing black magic for Black people. Maybe you’re not surprised that many of these women call Chicago home. What is it about Chicago that makes women confident that they can raise the dead?

You’ve heard of Ida B. Wells – arguably the best detective, lady or otherwise, the nation has produced and surely the strongest female lead there ever was. You’ve heard of her innovative use of social science methods in the fight against premature Black death. But you may not be familiar with her magic, how she, as Juliet Hooker writes, reanimated Black life extinguished too soon in her work. You’ve encountered a picture of Mamie Till Bradley, mother of Emmitt Till, at Illinois Central Station or at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ on the South Side. You may not know that she is responsible for what Christopher Metress calls the first of many “incarnations” of her son. These Chicago women bequeathed a great deal to us, but they have passed on. I am here to tell you that there are witches in your midst.

Some of them are subversive scientists by day. Take trina reynolds-tyler. A South Side native, she is an abolitionist and trained restorative justice practitioner. reynolds-tyler is data director of Chicago’s Invisible Institute. She leads the team behind “Beneath the Surface,” a data science project that uses narrative justice and machine learning in an effort to get a better understanding of how marginalized communities experience police violence and that “investigates the intersections of gender-based violence and policing.” reynolds-tyler worked with Sarah Conway of the City Bureau on the Pulitzer Prize winning “Missing in Chicago” investigation of the Chicago Police Department’s handling of missing persons cases. The investigation noted that “Chicago’s missing persons crisis is a Black issue” as two thirds of all missing persons in the city are Black and, according to police data, Black women are 30% of the missing, despite comprising 2 percent of the population. But it’s worse than even this. reynolds-tyler and Conway reported: “From 2000 to 2021, Chicago Police categorized 99.8 percent of missing person cases as ‘not criminal in nature.’ Our investigation calls this number into question. Our reports found 11 missing persons cases that the department listed as ‘closed-non-criminal’ even though the victim had been murdered.” More broadly, they reported:

“While police officials have publicly claimed that services for families are equal and fair across race and ZIP codes, massive gaps in missing persons data make it impossible to prove, […]interviews with current and former police officers, national experts, and researchers, along with dozens of anecdotes from impacted family members, reveal a pattern of neglect, incompetence, and illegal behavior from police officers in missing person cases. Under Illinois law and Chicago police policy, police officers cannot deny a missing person report for any reason. However, reporters found dozens of people who say they were told to wait, or outright denied the ability to file a report—delaying investigations during the critical early hours of missingness.”

They continue:

Analyzing police data on missing person cases from 2000 to 2021, reporters found discrepancies that call into question the department’s data-keeping practices. […] Police records also show that, from 2017 to 2021, a little over 45 percent of cases are missing a key data point about the time and date police arrived to investigate these cases. And reporters identified multiple cases that ended in homicide that were marked ‘non-criminal’ in the data—as well as four cases where detectives explicitly noted that the missing person had returned home, despite family members saying their loved ones never returned home alive.”

There has been much talk in the fields of history and Black studies regarding what Saidiya Hartman calls the “violence of the archive.” reynolds-tyler’s work demonstrates the struggle deceased Black women face in entering that archive, the struggles their grieving family members must undertake for them to be counted among the slain dead. But she, like her political grandmother Wells, is both a scientist and a necromancer. She is confronting an agnotological project, countering the work that is taking place to ensure that we do not know when a Black woman has been killed. She is truly an old school detective though equipped with cutting edge methods. But with each lax or shoddy record she challenges and each absence of any record at all to which she draws attention, she initiates a resurrection, ensuring that the voices of those passed on remain with us as we work to change politics here on earth.

The magic going on all around you is not just about numbers. In fact, some of it is in opposition to the meticulous forms of counting in which we have chosen to engage. This work exposes our problematic obsessions. The book profiles women whose best magic trick is their subversion of the vile True Crime genre, including the worst parts of the lady murder industry, an industry replete with hybristophillic murderbiliia – serial killer playing cards, Ted Bundy coloring books. None of them confront this industry as directly, none so harshly criticize who True Crime works to humanize by taking the audience into the killer’s point of view, whose names we remember – whose nicknames we expend effort to create – and who the genre renders as objects, numbers, parts, as University of Illinois Chicago Black Studies Professor Terrion Williamson. Williamson is a scholar of the Black Midwest and of serialized Black death. She reflects on found bodies and lost names. She says, “ the name is but a glimpse of the life it archives, and life is something the archive rarely accords victims such as these. It is instead death – violent, torturous and unrelenting – that acts as the remainder. Bodies left in bags on public sidewalks. Bodies discovered burning in the trunks of cars. Bodies rotting in attics. Bodies found naked. Bodies found strangled. Bodies found desecrated and dismembered. Bodies never found. If and when the headlines come, it is the bodies that compel them. No. It is the body count. The death toll becomes the (origin) story. To the extent that the bodies matter it is because the numbers have threatened to overwhelm the populace. Violence thus begets value, and the publicity attends not to the lives that were lived but to the savagery that made those bodies available for public consumption in the first place.”

I appreciate the questions she asks from here: “What, then, can be the resolution? Is there any possible virtue in rendering the depravity of Black death visible, or are we resigned to a vicious dichotomy – either neglect counting altogether or be consumed by the numbers.” She suggests alternate ways of knowing and what else there is to be known. This lady detective (and honestly this gifted writer and true poet) is not searching for bodies; she is out there searching for lives. She directs attention to the familial and communal life-keeping, as well as their reckoning, as part of the important but oft-unrecognized “what else has happened here” that attends serialized Black death. Williamson, like reynolds-tyler, draws attention to the long-suffering, long-laboring, unheralded familial and communal life-keepers who attend serialized Black female death, and she gives voice to their work in her assertion “we are what else has happened here.” I hold that an important part of what else happened is magic, necromancy. Miraculously she resurrects Brenda Erving, a woman slain in her native Peoria, giving us a glimpse into the interiority of Erving that the book about her killer never afforded her, by focusing our attention on an actual object, one that was extremely precious to her, a spoon ring. It’s a miracle I encourage you to witness for yourself.

NONFICTION

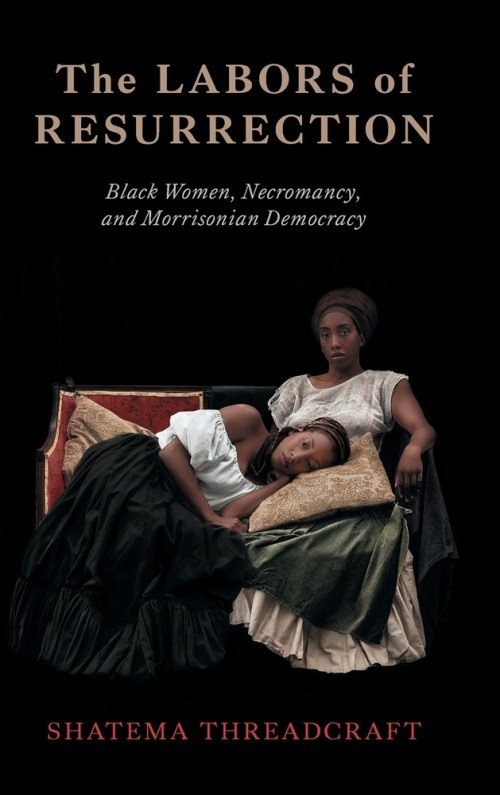

The Labors of Resurrection: Black Women, Necromancy, and Morrisonian Democracy

Oxford University Press

Shatema Threadcraft

Published October 28, 2025

Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies, Vanderbilt University