Caroline Macon Fleischer’s new novel, A Play About a Curse, could only have been written by someone steeped in the particulars of metafiction discourse. As an educator, Fleischer is always chipping away at the segmentation of genre, prescribing her students a voracious diet of cross-genre works from Susan Choi to Marjane Satrapi, from YouTube fictional video games to memoir vlogs. So it’s no surprise that her own work defies categorization. A Play About a Curse, which treads water between a flash play and a novella, is elusive in its hybridity. In Fleischer’s own words, she “loses control of the plot.” Upon closer inspection, the stars in Fleischer’s sky are suspended from strings. The world is a stage. We were always trapped inside a play.

Rachel Robbins

I’m very curious about your intentions with regards to genre and rule-breaking. Why write a novel that’s really a play, and a play that masquerades as a novel?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

In 1949, the writer Joseph Campbell published a book called The Hero with a Thousand Faces which is essentially a riff on Aristotle’s Poetics and Carl Jung’s analytical psychology. It’s super cool because it breaks down a tragic hero’s journey into 12 steps. I outlined A Play About a Curse strictly to that structure.

Rachel Robbins

Do you call it a novel? Or is it something else?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

I like to think of it as a magic trick! I tend to refer to it as a book instead of a novel or a play. Throughout the process, I got so excited thinking about all the possibilities of what a book is and can be.

Rachel Robbins

What compelled you to write a tragedy about women in theatre? Why did you choose to emphasize the jealousy and imposter syndrome that permeate relationships in the arts?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

Theatre is a uniquely heartbreaking industry. It is a niche, small world and the chances of feeling alienated, under scrutiny, or even exiled are high. If you look at whose plays are being produced or who’s directing those productions, the list is small. I don’t believe there are only ten good playwrights in America, but seeing the same names over and over can trick you into thinking that way. Thousands of talented theatre artists spend their lives wondering why they’re not invited to the popular kids’ table and never get an answer.

Rachel Robbins

The book is rife with references to the trials and tribulations of women creatives. Are female artists cursed?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

I don’t think we are cursed. Most women in the arts are supportive of each other’s endeavors. I’ve been thinking about a Doja Cat lyric in her song “Woman” that says, “They wanna pit us against each other when we succeedin’ for no reasons.” I believe girls and women share an instinctual bond to one another, so there’s a specific ache that comes with disappointing or being disappointed by another woman. When female relationships don’t work out, it’s very painful.

Rachel Robbins

In the book that pain is disorienting. We lose track of what’s real. Meta-drama is certainly nothing new, with canonized work from Shakespeare to Tom Stoppard featuring plays within plays. But you create an eerie mirroring effect rather than using the device to advance the plot.

Caroline Macon Fleischer

Thank you! I wanted the book to point to itself without being a play within a play. Near the end of the book (and this isn’t a spoiler, just context), you learn the protagonist’s file-name working title of her play is A Play About a Curse. There’s almost a moment of: “Wait. Am I reading Corey’s play right now?” But it isn’t that. You’re still reading a play by me, the author, that’s been named after the working title of Corey’s play. I listed myself as the playwright on the character sheet in the beginning so if anyone flipped back, it would feel like a bit of a hijinx.

Rachel Robbins

Speaking of Corey’s play, her research centers on Lake Annecy in France. That strikes me as another mirroring—a curse within a curse featuring another Faustian bargain. How do these nested structures work differently than traditional metatheatre, and what drew you to this specific location?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

As an artist, you will get a kick out of this. So this concept artist Joan Fontcuberta is, like, committed to the bit and invented a whole archaeological discovery in France of a made-up human aquatic species. It’s a whole thing—a fake priest comes upon the fossils at Lake Annecy, Nessy-esque (but better) photodocumentation supports the discovery, and it’s covered in fictitious news articles. But what’s amazing about it is the exhibit is featured alongside actual history in the Château d’Annecy museum. I renewed my passport and went to France to see it. What’s exceptional about this series is it makes you think about how myth is as valuable to history as “real” facts.

Rachel Robbins

For those of us who may be unfamiliar, can you explain the folklore behind the Mélusine, and why you chose to structure the narrative around that allusion?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

I picked the Mélusine as the aquatic creature for this story because I wanted it to be regionally relevant to the Swiss Alps, where Annecy is located. Also, I didn’t want to shy away from ugliness—the Mélusine is part reptile, more gruesome than mermaids. She’s in a few European folktales as a legacy of betrayal. A Play About a Curse mostly focuses on one fourteenth century account where Mélusine is cursed to live as a two-tailed serpent every Saturday—and no one is to know. When Mélusine marries, she asks her husband to trust her and keep away from her on Saturdays. Unfortunately, he can’t handle the mystery of what she’s up to on the weekends and spies on her while she’s in the bath. As a consequence, she is forced to live eternally as a dragon. The brutal part of this specific curse is the lack of logic to it. When others break their promises, the cursed is the one who pays. To me, it also functions as a cautionary tale, to not be too trusting. In my book, I wanted to explore that tragedy—getting punished for other people’s wrongdoings—and how oftentimes the burden of doom falls on whoever was already doomed in the first place. Also, the Mélusine is on the Starbucks cup. Now you can’t unsee the two tails!

Rachel Robbins

I had no idea! Then that myth is more pervasive than ever. Later in the book, when the fourth wall disintegrates, you don’t tread lightly. “DO YOU TRUST THIS IS REAL? WHY OR WHY NOT?” (page 182). What are you calling out about fiction and art by shaking us so violently out of the story?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

I wanted to question a big difference between literature and performing arts (both plays and movies). In the book, Corey says, “Playgoers are more willing to take a story at face value,” and it’s true. Readers seem very interested in finding realism in books, yet the top grossing movies of 2025 are Ne Zha 2 (a bid with a rainbow lotus), the Lilo & Stitch live-action (a Hawaiian girl befriends a runaway alien), and A Minecraft Movie (a ragtag crew of friends finds a portal into a weird cubic universe). Tracing back to—what—500 BCE, everyone gathered up in the amphitheater to hear about how Medea murders her own children after being left for a younger woman. Corey also jokes in Curse, “Leave it to medieval people to wear a mask that renders them unrecognizable.” You look at Shakespeare plays where they’re putting on costumes and gender swapping to dupe their loved ones. Audiences aren’t going, “Hm, would this actually happen?” They believe the story because it is the story.

Rachel Robbins

You quote Brecht and call relatability “limiting” and “self-infantilizing,” leaning into alienation as a means for intellectual engagement. Yet the need to relate to main characters drives much of the literary marketplace. Why challenge this trend?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

I majored in playwriting at The Theatre School at DePaul which is an intense conservatory program. During my time there, my favorite playwrights to study were those who are stylistically estranged. I find joy reading characters who feel alien to me. It doesn’t feel good, but is that our dopamine addiction talking? To read—let alone write—evil honestly feels icky. But it’s mind-expanding to indulge in stories outside of our perspective, whether the differences are cultural, mystical, or moral.

Rachel Robbins

I ask because several years back, I had the opportunity to interview you about your first novel, The Roommate, and we discussed the particular pressure to pen likable female leads. Corey doesn’t seem to have any sort of moral compass and is an entirely corrupt character. Do you care whether she is liked?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

It’s so great you are interviewing me again. I’ve grown a lot as a writer since The Roommate and daydream about what I’d edit now to give Donna more depth and color. In A Play About a Curse, Corey is utterly bad to the bone. But she is also weird and funny. I had a blast writing all her bizarre thoughts and behaviors. Why should I have to invent some traumatic backstory in order to make my evil protagonist likable? Whatever happened to the characters with mustaches and capes?

Rachel Robbins

You also ask profound questions about the art form itself. “When does a play end? Does a play end at blackout? … How about when the theatre shuts its doors? Or does it go past all that? Does a play end when the playwright dies? Does it end when the last person who remembers it forgets? Or does a play go on forever?” (183). Aside from being a stunning departure into philosophy, what did you hope to address by asking these haunted questions about the impact of art on the mind?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

The questions kinda mirror how people wrestle with life and death. We can’t be sure who’s right, so everyone gets to be right. I’m of the belief the character Maxine shares: “I believe we discuss plays in the present tense because they exist in a world that is simultaneous to our world.” Interestingly, her view on death is the opposite—she’s a rationalist who believes life ends when time on Earth ends. My views on the matter are ever shifting based on what stage of life I’m in, seasons of felicity or grief, or just new experiences.

Rachel Robbins

In her tragic final act, Maxine becomes punctuation: “The bedsheets told the story of her last movements: how she’d curled inward like a comma” (188). That struck me as another form of metadrama, or metapoetry, in that this is a play that is intended to be read, not performed, because of its beauty and its celebration of typography. Do you agree or would you like to see it come to life?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

Ah! I like how you point that out. It resurfaces again later when Corey’s body curves into a question mark. The physical object of a book itself is theatrical, between the cover art and typography and just how it feels in your hands. As for my vision here, the medium is open to be toyed with. Plenty of fodder for book clubs, actors in need of monologues, as well as playwrights and directors that want to practice adapting scenes.

Rachel Robbins

Why is the sort of minutia of daily typography so inspiring to you? Are we missing something that’s right in front of us?

Caroline Macon Fleischer

I think we are missing something! I think it’s curiosity and interest in whatever is in front of our eyes. I’m inspired by the idea of interacting with or finding poetry in daily minutia because it’s something I also struggle with. Moments where I’m able to ground in and awe at what’s in front of me feel like glimpses into the point of it all.

FICTION

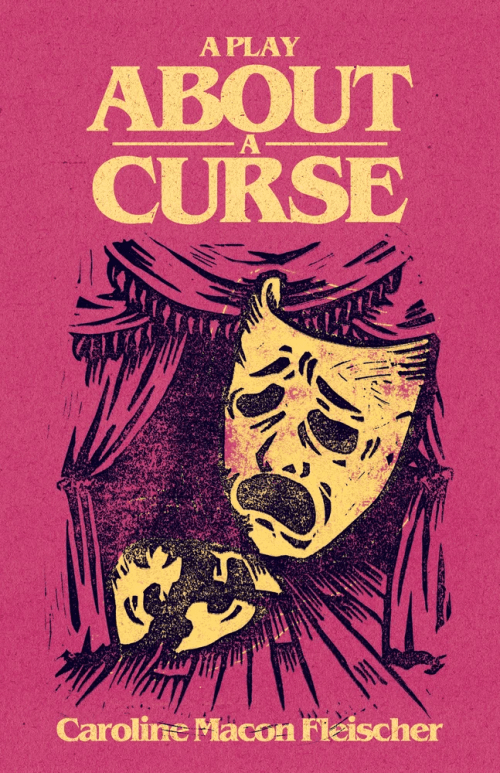

A Play About a Curse

By Caroline Macon Fleischer

Clash Books

Published October 21, 2025

Rachel Robbins received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is a tenured assistant professor at the City Colleges of Chicago. A visual artist and two-time Pushcart Prize-nominated writer, her paintings have materialized on public transit, children’s daycare centers, and Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. She is the author of In Lieu of Flowers, available through Tortoise Books, and The Sound of a Thousand Stars, available from Alcove Press, Penguin Random House Audio, and Hodder & Stoughton, an imprint of Hachette UK. She lives in Chicago with her husband, children, and Portuguese Water Dog.