Hannah Pittard’s If You Love It, Let It Kill You is a masterclass in eccentric ennui, existentialism, and uneasy contentment writ large. The book’s bouncy dialogue draws the reader in and doesn’t let go. Her balancing of the absurd and hyper-realism captures what it is to be a woman, and a human, in 2025. Kevin Wilson’s review of the book is telling: “Real-life, the strangest place to reside, is where Pittard does the most incredible work.”

I spoke with Hannah about her deft usage of the chorus, the challenges and payoffs of teaching and mentoring young writers, real-life events that seeped into the fictional plotline, and whether or not a book with a talking cat is fictional.

Content warning: The novel contains flashbacks to sexual violence.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pete Riehl:

I’ve seen maybe one or two episodes of Gilmore Girls, but from what I’ve seen, oh my God, the dialogue is just snappy. That’s what I feel like with the family in If You Love It, Let It Kill You. Jokes and highbrow and lowbrow and this is a quick-witted family. In your house, was everybody well-read, and maybe in academia?

Hannah Pittard:

My mother is a teacher, and my sister and my brother are both older than I am. Growing up, I had them both on pedestals, and they fought all the time. But even the way they fought was intimidating and wonderful to listen to.

I have been co-opting my family’s lives for a while now. The book is fiction. It’s 100% fiction. When I first handed it in and the publisher [said] “Well, we just want to make sure you’re calling this fiction, you’re not calling it nonfiction.”

My agent and I kept saying, “There’s a talking cat. In what world am I calling [it nonfiction], right?

I like to write about fictionalized versions of me and my sister because we’re very, very close, and we crack each other up, and she’s just been so supportive, and she’s one of my biggest muses. But I was telling her-she hasn’t read the book yet-“People love your character. I promise people love your character.”

She was like, “They always love my character and it’s not me, it’s you-you’re all the characters.”

And I [said], “Yeah, but I give you the best lines and she [said], “But I didn’t say them.”

“Nobody knows that.”

Pete Riehl:

Early on, Hana lists some of her issues: children, routine-she definitely does not like routine. She’s talking about what’s going on in her life, including that her dad has what his ex-wife classifies as “FOMO.” After 40 years or so of since the divorce, he has moved back, and so the family’s all within like a one mile radius. Hana is tired of men and is having an existential crisis brought on by the horrible story [written by her ex-husband, in which a character seemingly modeled after her is killed]. We learn that Hannah’s husband had cheated on her with her dear friend. We learn that she’s not hugely enthusiastic about being a stepmother. She’s not technically a stepmother, but Bruce’s daughter is 11 years old, and Hana feels like [being a stepmother] is a role to be skirted around. Is that safe to say?

Hannah Pittard:

I think so. In the book, she is definitely struggling with this contentment that she’s discovered, that she has sort of fallen into, and she’s nervous about this, what it might mean for her art and her future. Also, the entire thing is from a point of privilege, right? It’s from a place of privilege that the whole story is being told, and she’s in this situation with this incredibly loving dude, with this incredibly loving child in her life, and she’s got a family member, her sister just across the street and her mom just down the road, and her father-she is surrounded by and being sort of buttressed and held in place with all of that love in that environment. She takes that support and uses it as an opportunity to lament what’s missing. And of course, if she didn’t have it, she wouldn’t be able to have the anxieties that she has.

So it’s definitely a Catch-22 and hopefully readers will see that I am making fun of a person who has been appropriating other people’s lives for her entire career, and then someone does it to her and she doesn’t like it.

Pete Riehl:

Hana [the protagonist] is a professor, and there are parts where the students are given one voice, as if they’re speaking as one [being]. I love the interchangeable [names for the students in the class], like Michaela, Caleb, McKenzie, and how she has a map on her hand, cheat[ing] [to remember the names].

There’s a character in the book, “The Irishman,” and we don’t necessarily see him that much, but his presence casts a shadow throughout. This leads me to wonder how much of this book is about the archetype and the chor[us], as seen with the students as a whole. Even in the book’s blurbs and on the cover, there is a lot about choral nature.

[For The Irishman] do we need to know his name, or is he representative of all men, or a certain type of man?

Hannah Pittard:

So that’s interesting. Maybe the Irishman might be representative of-within the world of the book if it had to be representative of something-and this doesn’t have to be for women only, it could be for men, women or whatever gender, but he is that something from your past that is unknown and murky and unanswered, unsolved. That could be anything, right?

That could be if you had a kid who went missing, if you had a dog who went missing, but there’s an aspect of her memory that is gone and it’s connected to this guy, and that feels very out of control to her and not good.

With regards to the students, I like playing with the idea of mentee and mentor-when the teacher stops being an effective teacher and when students start teaching the teacher. I mean, I could have used the Marv Levy quote (the epigraph for Hannah’s We Are Too Many: A Memoir [Kind of]) with this book, too: “You don’t change with the times, they’re going to change you.”

The students operate in two different ways: sometimes they are individual students who really come through, I hope, as pivotal characters-Mateo, Willow, Tiffany-the gray haired, non-traditional [student]. They are these sort of side players, but that’s a real part of her life, right?

There’s the home life, but then when you are somebody’s teacher, it is a big responsibility. It’s not the same as being someone’s parent or somebody’s step parent, but those relationships are pretty intense, and they’re also short-lived. It’s a revolving cast of characters, and so there are those individual students who are clearly sort of messing with her, and one of her struggles is what’s appropriate all the time; she has no idea what’s appropriate: Can I write about my family? Is that appropriate? I write about my students. Is that appropriate? It’s not appropriate for them to write about me.

But then sometimes when she’s not with her students, she’s thinking of them, and [she has] condensed them into, she’s turned them into, instead of an angel and a devil on her shoulder talking to her, her students are calling her out constantly, especially about the book that she’s writing, like, “Where’s the plot?”

I came up with that just because there was a day when I was working on this book early on, and I just started laughing, and I was laughing because I was doing something that I told my students [not to do].

Pete Riehl:

The students/teacher dynamic is so fun and helpful to the plot.

Hannah Pittard:

I really remember that day where I was cracking myself up about how many times I ha[d] told them they can’t have talking animals because animals don’t talk. Then I [thought], I should totally let them break in [at this point in the lesson] and accuse me of it. Once I started doing that, I realized I wanted them to [challenge the rules]. I loved the idea on a very lower level somewhere within this narrative, [of the book] as a primer on writing-it teaches exclamation marks, what’s italicized, and there’s even a part where she names Mateo early on, [despite what] she always tells her students: only name the pivotal players, and then she also tells them to name everyone.

Pete Riehl:

Can’t be both.

Hannah Pittard:

Exactly. So right away, we see that her advice is conflicting.

I find that it’s really important if I’m going to be even performing, writing about myself-and that is what it is, a performance-I feel the need to make sure I have a lot of self-deprecation and antagonisms towards me, because otherwise I would just be so sick of it.

The students, I think, are also there to put some oxygen into it and also to poke holes in her balloon every once in a while. Any time I think that the narrator is getting too close to being too full of it, here comes a student. Or a talking cat-something that’s going to puncture her inflated ego or her inflated self.

Pete Riehl:

The students are demanding more. I’m so interested in the dynamic between Hannah’s professors and the students. It is so well-done. You can tell there’s an affection there, or else they wouldn’t be able to be so honest.

They’re brutally honest and they say, “You told us not to introduce something so late in the story and that this wouldn’t work-how come it’s okay for you?”

There’s that parent kind of thing, where you say, “Well, that’s just the way it is.” Or “Rules are there to be broken.”

Hannah Pittard:

One of my favorite things that Willow says-and Hannah is just imagining it-”Oh, great, next thing we know, there’s going to be a dream.”

About 100 pages later, finally, we do get a dream of a dog. When I wrote that, I just thought, Ah, Willow’s right; there is the dream, because in creative writing classes, one of the things is “don’t write about dreams. I remember my students telling me this once. They told me, “Well, you’re not supposed to write dreams,” and I said, “What are you talking about?”

Part of this book is also the way that I’ve learned what other creative writing teachers say, and what [writing teachers] are supposed to be saying, and also how much I’ve changed because I would never tell a student they can’t have a talking animal now. That’s also because I have changed with the times and I have grown up, and I understand that realism is not the only genre out there.

I’m also really clear with them that there’s a certain type of story that I am best at helping, but I’m game for helping any of it, and I’m just more open to just about anything since I turned 40. I don’t know, it’s like your brain realize[s], Oh, okay, this is life, this is it. Why am I being such a stickler?

And then Covid [hit], and the 40s and Covid at the same time, I’m like, “Let’s do it. You want to write about Covid? Yeah, let’s do it.”

Pete Riehl:

“The Irishman” is a pretty scary character. If and when we get that movie (crossing fingers), he could easily be played as an archcriminal.

Hannah Pittard:

I’m very happy to hear your interpretation of that; this is what I will say about the Irishman: The Irishman is not real. It’s introduced in the plotline, that before [the protagonist’s] husband cheated, [the protagonist] cheated, too. This comes very early, so I’m not giving away anything, but I needed to signal to the reader that this is not a story where I’m going to try to put a fictionalized version of myself on a pedestal. I really want to indicate early that it is a problematic exploration of identity and self.

When I was in grad school, there was an evening very much linked to decades ago, and that one night has haunted me, and it comes up sometimes. Depending on what I’m going through, I think about it more often than other times, and sometimes I can go years without thinking of it.

It has haunted my adult life, and I was asking myself how I create a character who can represent a bunch of other things but can collapse that decades-long haunting, put it on the page, and have it haunt her immediate life. Hearing you talk about it made me think I did it, at least for one reader. I did the thing I wanted to do, and I feel I’ve been doing this since my very first book, When a Girl Goes Missing. There are so many of these books where girls and people and young people go missing, and there is often a satisfying resolution, [which] might be sad, but we find out. I knew from that very first book to this current one that I wanted my fiction, no matter how unlike real life it might be, how absurd-because this new book is absurd-I wanted it to emulate real life in that way. Uncertainty is like what we live with every single day, and I didn’t want to wrap that tidiness up.

Who even knows if it’s this guy texting her? The only time she’s actually seen him was in a car. And was it him? Was it not him? And even the students are saying “This is so convenient and, like, did we actually see him?”

I wanted it to be this sort of darkness at the periphery, and I also wanted to show how dark and light can exist at the same time, like you can be having something really horrible in your home life, and then you go into work and you have a good day, or vice versa. Work could be a nightmare for you, but you love getting home and giggling, and it doesn’t matter that the next day isn’t going to be a traumatic struggle for you. I really like pitting highs and lows, pluses and minuses, dark and light.

This interview is excerpted from Episode 286 of the Chills at Will Podcast. Listen to the complete conversation here.

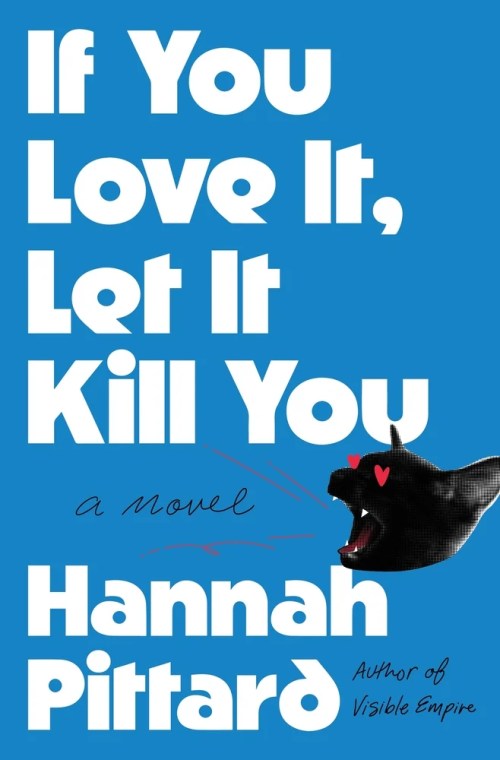

FICTION

If You Love It, Let It Kill You

By Hannah Pittard

Henry Holt and Co.

Published July 15, 2025

I am a high school English and Spanish teacher, and the host of The Chills at Will Podcast. Previous guests of podcast include Deesha Philyaw, Jeff Pearlman, Jean Guerrero, Jonathan Escoffery, Morgan Talty, Taylor Byas, Steph Cha, Gabby Bates, Luis Alberto Urrea, Justin Tinsley, Jordan Harper, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Allegra Hyde, Matthew Salesses, Dave Zirin, Nadia Owusu, and Father Greg Boyle. You can find me on instagram, @chillsatwillpodcast, or on Twitter, @chillsatwillpo1. I love to play basketball and tennis, read, study Italian history, and spend time with my two little ones and my wife. My favorite authors include Mario Puzo, Ernest Hemingway, Steph Cha, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Tobias Wolff. I have published four short stories in three online magazines, American Feed Magazine, Circle Magazine and The Paumanok Review, as well as four in print in The Writer’s Block, Short Stories Bimonthly, Storyteller Magazine, and The Santa Clara Review.