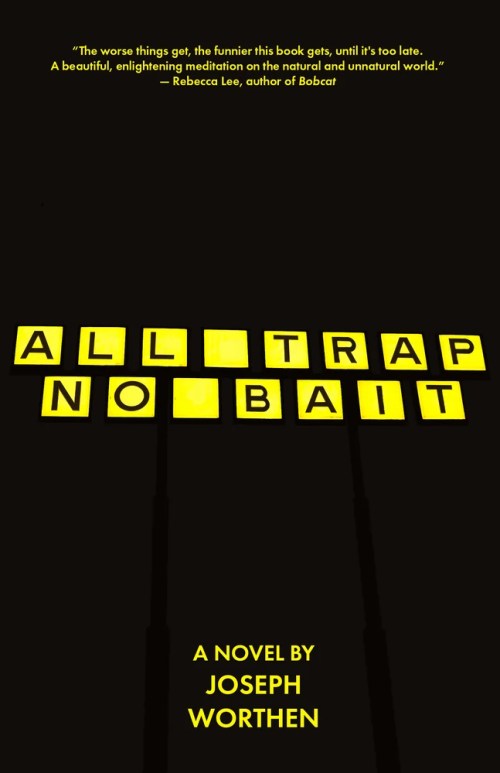

We are now well beyond the early optimism of the internet with its promise of pluralism, connection, and democratization. What we’ve gotten instead is more like a tsunami of our collective id, a relentless force containing humanity’s most base impulses. In his delightfully reckless debut novel All Trap No Bait, author Joe Worthen attempts to surf this destructive wave. To call this novel dark would be like calling a Chicago February cold. The language is not adequate for the experience.

In the Covid-ravaged summer of 2020, Beverly Jane Ornett (Bev), a twenty-four-year-old marginally employed college graduate, makes a pact with an internet demon (in exchange for some obscure eyebrow-threading tutorials) with consequences both real and surreal. Foreshadowed by Bev’s ex-boyfriend’s promise of a Red Rabbit Deluxe ice cream sandwich (a moment akin to Alice’s “Drink Me” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland), Bev’s journey down the rabbit hole is filled with a phantasmagoric parade of curiosities: suicide-obsessed rappers, violent frat boys, secret poetry societies, neo-Marxists, strip mall vitamin salesmen, and pool parties as endless as the supply of drugs.

But amidst all the Xanax, kudzu, and cockroaches, Worthen brings a sense of humor and an unwavering eye for detail that tempers the misery, much like watching your favorite sit-com in a trashy motel. The result is a mysterious yet delicious intoxicant wafting fragrantly from a Solo cup as it’s passed from sweaty palm to sweaty palm on a humid night in Mobile where you feel just hopeful enough to take chances.

Jeremy Wilson

First of all, congrats on your debut novel! Getting a book out there is tough, so I’m always interested in the path to publication. Tell me about the origins of the novel and how it ended up landing with Chicago’s Tortoise Books.

Joe Worthen

Thank you! My path to publication has been very difficult! I’ve been attempting to publish novels for more than a decade without getting much traction. I’ve had hundreds and hundreds of rejections from all sorts of people and publications. Often the subject matter, the focus on contemporary technology, was cited as a deal breaker. All Trap No Bait was an attempt to write a more character-focused piece which still indulged my preoccupations with the internet and online culture. I had been submitting ATNB for close to a year, and as I recall I submitted it to Tortoise Books on the first day of their open reading period. Jerry accepted it pending some revision. Tortoise Books has been extremely supportive throughout, and I’m grateful to have gone through the process of publishing my first novel with them.

Jeremy Wilson

If I was the algorithm, I’d say this book is for fans of Ottessa Moshfegh who wish she was Southern. Do you consider yourself a Southern writer? And what does that heavily-loaded label mean to you?

Joe Worthen

First, I love Ottessa Moshfegh, and My Year of Rest and Relaxation was definitely an influence on ATNB. I do consider myself a southern writer mostly because I derive my material from my life, and my life has occurred primarily in the Carolinas, Louisiana, the internet, and briefly Atlanta. It is a little weird to claim a region when that region is basically a big parking lot with the same Dollar Trees, Shoe Carnivals, Sports Clips, T-Mobiles, and Cash Advances repeating ad infinitum. The south is choked with these placeless branded spaces (very much like the internet), but even these places take on a character when you are submerged in them for extended periods of time, when they are the backdrop to the bulk of your human experience. It can be difficult to translate these spaces into something that is perceived as literary, but I think it’s necessary to try. I think being a southern writer is mostly trying to find some meaning, some beauty, in the suffocating Bible-flavored nihilism which structures daily life in this sometimes hopeless place.

Jeremy Wilson

In a recent essay for LitHub, the writer Lee Cole discusses the underrepresentation of class backgrounds in MFA programs and, as a result, in literature and literary institutions, “creating a cycle of class reproduction.” Your novel centers characters who have to carefully consider going into deeper debt just to order breakfast, so class is clearly on your mind. Does Cole’s argument resonate? Is class background an overlooked identity position in fiction?

Joe Worthen

There certainly aren’t many authors out there as openly hostile towards their own fictional characters as Moshfegh, haha. Cole’s argument resonates very much with my experience of growing up in the south and getting my own MFA (though I got mine at UNCW). He also does a good job attending to the complexities of class as identity in that, you know, identifying on a deep level with a hierarchy in which you must work at a pizza restaurant to live might not be very empowering in the long run. And I do think that, yes, literature is a prestige and increasingly niche artform populated at basically every level—even in its audience—by the affluent, educated, and urban. The south as a region is basically the antithesis of this demographic (at least as it is imagined). For this reason, there will probably always be an overrepresentation of characters like Moshfegh’s protag in Rest and Relaxation, even if they are subject to derision, and fewer critically impoverished characters working at strip malls in Alabama. Though, like I said, I enjoy Moshfegh a good bit. What does bother me in terms of class and fiction is that strain of thought related to autofiction, where Cusk or Knausgård or whoever dictates that fiction should only represent what the author has directly experienced—the idea that making something up is embarrassing or gauche. This is great if you regularly travel to Greece to teach writing workshops, but less great if you work in a milieu without that literary patina—like a warehouse or a Starbucks. When autofiction is approached in this way it becomes a pretty naked method of laundering class privilege into literary prestige. Some autofiction is really great and everything, but that elitist tendency should probably not be championed so vocally. Literature might always skew towards the privileged, but we can maybe stop finding new ways to hardwire that in. I like to try to write characters outside of my immediate class experience, though my concerns and anxieties will probably always come through. Bev, like many other people, has it much harder than I ever did.

Jeremy Wilson

The novel takes place in the summer of 2020, a time where the experiences and effects of the pandemic were vastly different depending on class. What made that summer the ideal time to set Bev’s story?

Joe Worthen

Though I wrote most of the first draft of this during the summer of 2020, it wasn’t initially set during the pandemic. As I revised, I saw a lot of the isolation and paranoia of that summer in the book and decided to just commit to it. I think working-class life in America today is defined by precarity. Bev’s life only works if she has a roommate, if she doesn’t get sick, if her car doesn’t break down, if her job is consistently available. In concert with the demon, the pandemic provides the pressure to upset these conditions and to prevent Bev from stabilizing. Then the worst can happen.

Jeremy Wilson

Let’s talk about this demon. Without giving too much away, Bev is harassed online by a demon who wants her to do its bidding, and much like our personal demons, this online voice is too much to ignore. Bev is also plagued by nightmares of losing her phone charger, which is a literal lifeline. Why is it so difficult for Bev (and by extension any of us) to ignore the trolls and simply disconnect from the internet?

Joe Worthen

Bev has been on the internet since she was a child, constantly used it as a vector for socialization, and cultivated a range of her own profiles and blogs over the years. She still doesn’t totally understand the internet. Few of us do. The internet is massively complex in both its infrastructure and its cultural component. Seo-Young Chu refers to cyberspace as a “cognitively estranging referent,” or something too large and complex to be easily conceptualized without the help of metaphor. As Bev is harassed, she wonders about the limits of the demon’s “powers” because she doesn’t totally understand how the demon is able to do what he is able to do online even though Bev herself is fairly web-literate. The demon highlights the limits of Bev’s understanding of her world and challenges her to expand that understanding even though Bev would really rather not.

Jeremy Wilson

I keep thinking about the moment at the never-ending party where Bev adds her signature to a door covered in other Sharpied signatures, only to become “part of the illegible aggregate. Just black on black. A little less negative space for the next person to work with.” And then, after a paragraph break: “The party feels remote now.” I couldn’t help interpreting this as a metaphor for the internet: an illegible field of signatures, what was promised as a party has left us even more isolated. Given your preoccupations with the internet and online culture, tell me where we’re headed.

Joe Worthen

I like your reading of that moment! I’m glad the white space is doing some work. Despite the horrors visited upon Bev in this novel, I’ve had a pretty web-optimistic perspective for a long time—though that is harder and harder to maintain with every year that goes by. I love the egalitarian possibilities we were sold on the internet, and projects like Wikipedia are genuinely incredible. But the realities of capitalism have corralled the open internet into a few highly controlled spaces where most of what we see is advertisement (or AI slop at this point). I remember when the internet was wide and mysterious, when we had personal websites instead of profiles, when communication was unmediated and largely anonymous in chatrooms and forums. Bev’s poetry group, Dark Secret, is definitely indicative of my nostalgia for that era. Maybe AI will be the thing that wrecks social media and drives users back to a less centralized, more anonymous internet, but that’s probably just wishful thinking.

Jeremy Wilson

There were times when I was reading where I felt the presence of signs or codes, a kind of Pynchonian wink, especially with the names of characters and businesses. The suicide-obsessed hip-hop artist Noe Null, for instance. This can be read as a double negative or even as a pun: “know nothing.” This puts the reader in a similar situation as Bev, interpreting the clues to unravel the mystery, which is one of the many fun things about this novel. Am I way off here, or is this playfulness a part of your process?

Joe Worthen

Yeah, Pynchon has always been a big, perhaps overwhelming influence on my style. Of course, I’d love for Bev to be read as a somewhat less competent iteration of Oedipa Maas. I gravitate towards prose like Pynchon’s which seems to (and actually might) have little codes filigreed into it. I have tried to tone down my Pynchon-imitation over time as I’ve come to find that not everyone is as big of a fan of his thing as I am, haha, but the Pynchonesque names have stuck around. There are definitely some intentional word games in here, but the aesthetic of being encoded is probably more important to me than the code itself.

Jeremy Wilson

While Denny’s features prominently in the novel, the cover is clearly suggestive of Waffle House. I’d like to wrap this up by making everyone hungry for more, so please describe your novel as a Waffle House order.

Joe Worthen

Consider a triple hash brown order as the three summer months which serve as the base to Bev’s experience of debasement and metamorphosis. Into these steaming, oily days, I have included the sautéed onions of unemployment, the waxy cheese slice of cyberbullying, and the unexpected ham cubes of Covid-19. Over the top, I have applied a liberal serving of malaise, represented here, fairly literally, by Burt’s chili. Or if you’re in a hurry: Triple. Smothered, covered, chunked, and topped. Scattered well.

FICTION

All Trap No Bait

By Joseph Worthen

Tortoise Books

Published August 5th, 2025