How to Dodge a Cannonball is the satiric story of Anders, a morally naive white teenager who joins the Union Army during the American Civil War. Anders becomes a flag twirler, eager to boost the morale of his fellow soldiers. Alas, before the narrative has even properly begun, Anders is captured, and ends up defecting to the rebel Confederate Army. It’s not long before Anders flees battle, and winds up back with the Union, now amongst an African-American regiment. Wearing a fallen soldier’s uniform, Anders fits in by claiming to be an octoroon, a person of one-eighth African ancestry. These defections are more than a reference to Stephen Crane’s classic Civil War novel, The Red Badge of Courage, they are the first movements of what feel initially to be a parodic, then earnestly serious theme.

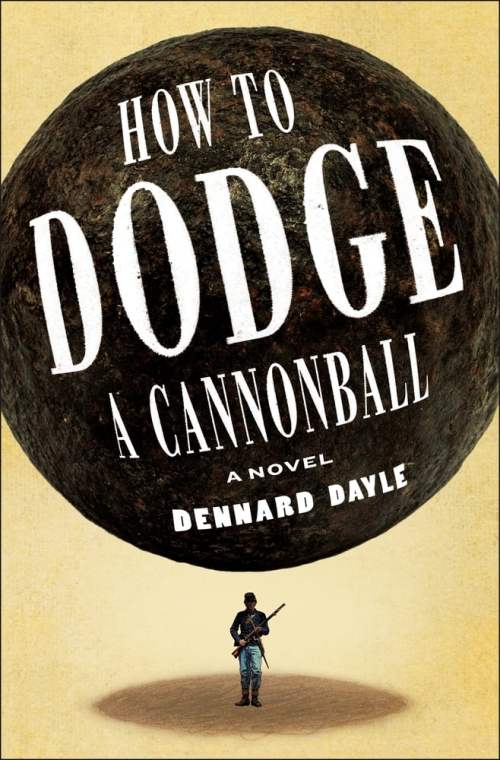

Dennard Dayle is a Jamaican-American author living in Brooklyn, New York. He is a graduate of Princeton University and received his MFA from Columbia University. His short fiction has appeared in such notable publications as the New Yorker and Clarkesworld. In 2022, he published a collection of short stories, Everything Abridged. How to Dodge a Cannonball (hereafter referred to as Cannonball) is his first novel.

Anders’ disguised identity as an octoroon works out pretty well, in part because several of his new comrades claim to be descendants of Thomas Jefferson and his slave Sally Hemings. (It is remarked, with the novel’s frequent tone of ambiguous irony, that “[Jefferson] loved both races, in his heart and his actions.”) Of the characters most important to Cannonball’s plot and themes are Gleason, Anders’s commanding officer and an aspiring playwright, and Patricia, a teenage girl in disguise as a boy soldier. Gleason’s art provides an important outlet to him, to the point of recruiting his own men as actors in his “speculative dramaturgy” or “scientific theater”—an 1860s stage version of speculative fiction and science fiction. Gleason creates these works in the classic motivation of speculative literature: to envision a possible, and possibly better, future. Patricia, in disguise and wielding more than four names and associative personalities, makes for a curious reflection of Anders as a recurring turncoat. Anders, Gleason, and Patricia’s unit moves from fighting in the South, on to New York to deal with draft riots, then out west to the war’s frontier in Nevada.

Approximately the last quarter of the novel becomes a speculative piece, a living dream within a bubble. While Cannonball is exaggerated in comedy, character behavior, and a style not perfectly suited to the 1860s (at one point the narrator discusses Anders’s id, ego, and superego), it is especially in this last quarter of the novel that the story becomes marked historical fiction. There are some suggestions of an alternate history earlier—Anders seems to reference George III of England being killed during the American Revolution—but it’s only in this final quarter that a strange opportunity enters the narrative, like one of Gleason’s theatrical pieces come to life.

Anders is proud to consider himself a “recognized master [of] morale,” visibly represented by his art of flag twirling. An authentic cheerfulness and an energetic personality reminiscent of ADHD bolster this identity. One arc of the story is the continual dissolution of this morale, a version of that popular theme of loss of innocence. When both sides of a conflict have contempt for your individual self (to put it lightly), the ideal of being a war hero begins to fall from its pedestal. But what ideal to replace it with? This becomes the overarching question of the novel. The ideal of fighting for freedom? Anders and his unit begin to find, because of their status, that regardless of outcome, real freedom and respect may be impossible. What about the pursuit of art? But art can fluctuate with the emotions of the artist and it cannot stop the crush of death, especially in wartime, and especially as a member of the underprivileged in America. Worshipped to the point of delusion, art becomes a consuming, introverted fantasy, and a fatal withdrawal from reality.

We will leave the novel’s conclusions to the inquisitive reader. Let us merely hint that the question of how to dodge cannonballs—despite the chaos of history, narrative, and shifting identities—is easier to answer than you might expect.

FICTION

by Dennard Dayle

Henry Holt and Co.

Published June 17th, 2025

Philip Janowski is a fiction writer and essayist living in Chicago. He is president of the Speculative Literature Foundation's Chicago Branch, a member of the Chicago Writers Association's Board of Directors, and a presenter with the late David Farland's international Apex Writers group. He has studied under such accomplished writers as Sequoia Nagamatsu, Martin Shoemaker, and Michael Zadoorian. His work in fiction has been awarded with an Honorable Mention from the Writers of the Future contest, and his major project is the upcoming Dominoes Trilogy. He can be reached by his Instagram account (@spiral_go), or by email at (philip@speculativeliterature.org).