Funmi Fetto’s first work of fiction, Hail Mary, surgically deconstructs the traditional Nigerian woman’s place within the family, society, and the world. Fetto uses laser focus in nine short stories to strip stereotypes of women down to their most heart wrenching core and highlights the double standards on Nigerian culture, marriage, motherhood, skin color, religion, and beyond.

2 Samuel 6:14—A story of duplicity.

Ifeoma, a pastor’s wife, lives a double life. Her husband is a cruel and unforgiving “man of God” who considers his behavior a necessary righteousness. When he burns the last communication from their sons in front of her—a letter admonishing her for allowing their father to treat them all so terribly—her faith in God also turns to ash. Unable to forgive herself for turning a blind eye to her husband’s brutality, Ifeoma devises a plan to escape the life where she is forced to ignore his philandering, accept his physical and sexual abuse, and deny her lack of agency. The strategy she employs to free herself she also keeps secret. When the tables finally turn in her favor, she rejoices and dances like David in the title’s Biblical scripture.

Unspoken—A story of silence.

James proposes to Amaka in front of his friends and family. No one realizes during their celebration that she never actually says yes. Nor does she celebrate. Once home, she reflects on what this future has in store for her. She also considers her past and how much of it she is obligated to share with James as her husband. Amaka and her brother Joseph witness an “incident” as children, but it’s something they both avoid discussing with anyone including each other, despite their attending counseling. They eventually grow apart leaving Amaka with little connection to her natural family and culture. By the story’s end, it’s clear that the “incident” surrounding her mother’s death is tied to her feelings about marriage, female autonomy, and so much more.

Hail Mary—A story of false hope.

Riliwa left her son and mother in Nigeria with the hope for a better life in London. Unfortunately, London is nearly as bad as her mother said. Riliwa does not have the necessary paperwork for immigrating to Europe. She’s constantly living in fear of deportation and considers herself an “ugly mother” for leaving her child behind. But when her friend Mary convinces her to pay a hefty sum for “official” paperwork, Riliwa thinks her luck is changing for the better. She returns to Mary’s house to get on with the scheme and discovers her friend was deported, dashing her hopes.

Homecoming—A story of reclamation.

“Homecoming,” the story that perhaps more appropriately anchors Fetto’s collection, is about Morayo stepping out from under the sheltering umbrella of her marriage to a white man and into the sun under which her own culture shines. Though she did love her husband, she realizes after his death just how much of herself she’d lost. Their children know almost nothing of their Nigerian roots—their tongues do not know the food or the language. She spends a significant amount of time by herself simply remembering. She feels shame for allowing her authentic self to be minimized on behalf of a man who had his own secret that would ultimately lead to his undoing, and ironically, her resurgence.

Underneath the Mango Tree—A story of motherhood.

As Kemi helps prepare the food for her sister’s wedding, she reflects on her own life, thanks to the thinly-veiled insults by the other women from her village, including her mother. She considers how much of a spectacle her sister’s wedding will be, probably because of her oft-mentioned beauty. She is fair-skinned, with soft hands and a straight nose. Kemi is almost the opposite: black-skinned, hard-working, and almost completely disregarded on her wedding day. The women gossip and taunt and make Kemi feel inferior and inexperienced because she is childless. The way the women spoke about her made her take drastic action that finally results in pregnancy, but at an enormous cost.

Wait—A story of authenticity.

This story is a first-person view of a marriage and family at a major crossroad. It’s a confession. The narrator discusses with her husband about her friend Ngozi, who appears to prefer same-sex relationships. The narrator wonders how much others know about Ngozi’s lifestyle and past partners, of which she was one. Ngozi awakened a sensation that the narrator wants to experience again and is grateful her friend, and former lover, showed her a freedom her traditional marriage—that she did not particularly desire—would never afford her. So, she makes a choice that will alter the lives of her entire family, but will also give her the inner peace she’d always dreamed of.

Trip—A story of expectation.

Lara is a teenager who loses her mother and learns she is moving to London to stay with her aunt, uncle, and cousins. She remembers tales of them and how well off they were. Many African families chose the dream of being educated and making a living in London, this is true for many of Fetto’s characters. Lara is excited for the life awaiting her until the rose-colored glasses fall away from her eyes when she arrives. She see’s the beautiful aunt from the pictures is actually not that well put together with her crooked wig and knock off name brand clothes. Her uncle is a porter at a major hospital, not a doctor. She fears she will actually be worse off because they do not live up to her expectations. Immediately regretting the decision, Lara begins to long for home even though her “trip” has just begun.

Housegirl—A story of shame.

Nkechi works for a cruel couple—the woman constantly berates her and the man creeps into her room at night. A theme throughout the stories is the treatment of women’s bodies. How other people treat them, but also how women treat themselves. Nkechi feels nothing but shame every time her right to exist is infringed upon by the couple. Unfortunately, she feels as if she must settle for her situation, dealing with the abuse and accepting that her dreams of obtaining more are impossible as she sends every penny home to help care for her disabled mother and younger siblings. Her situation only worsens, bringing her shame to a crest that overtakes her and seals her fate.

The Tail of a Small Lizard—A story of guilt.

The final story is another confession. A Yoruba woman who feels she is an accomplice to a fatal bus crash as a teenager, writes about it in a letter to an associate as a therapeutic exercise. A new high school teacher arrives and everyone is smitten, including her mother. The narrator’s grows to dislike her teacher who flirts with his underage students and steals her mother’s much desired attention. It helps her bond with a young man Bakare who is also envious of the teacher’s self-importance. An incident between the teacher and Bakare ends with the young man seething with anger and embarrassment and retaliating. His actions lead to the crash and the narrator struggles with her complicity.

Funmi Fetto—The storyteller.

The theme that cuts through Funmi Fetto’s short stories is clear—women are constantly under attack by men. The book begins with Ifeoma rejoicing because her husband finally dies from her slowly poisoning him. Why must she go through such lengths to obtain peace and the right to exist within an un-abused family? So many of Fetto’s characters see marriage as a weapon against women. Single women are shamed for being promiscuous or not wanting sign up for a husband’s infidelity and sexual abuse—toward them and their children—that marriage surely brings. It is a toxic double standard that perpetuates a generational cycle of criticism toward women who attempt to challenge tradition and trauma for those who follow it.

Hail Mary also pushes back against the white/Eurocentric gaze. The juxtaposition of Kemi, who is dark skinned, and her youngest sister Ronke, who is lighter with straight features is galling in “Underneath the Mango Tree”. Ronke treated like a precious baby whose beauty everyone dotes on, so much so their mother told her to use an umbrella to keep the sun from darkening her skin. Colorism has a significant presence within Nigerian culture, according to these stories.

Thankfully, Fetto does not only point out the failures within Nigerian culture, but also shows reverence. No story is more uplifting of Nigeria than “Homecoming.” If Fetto used it for the book title or as the final story, the collection would have felt more hopeful. Readers get to walk alongside Morayo as she indulges in her culture. She strolls through the markets searching for food to sate her hunger while also reminiscing about her childhood in Africa eating dishes prepared by her grandmother. The trek stirs up memories about her and her brother’s mischievous ways in the kitchen. She speaks to the vendors in Yoruba, a language that now feels strange in her mouth. She remembers her national pride when telling a bus driver about her background. She rediscovers herself.

Morayo returns to her marital home and realizes the art and furniture that populates her house is from other cultures. And at that moment, she knows it’s time to go home to Nigeria. Fetto’s stories relay the complicated feelings surrounding where we come from, but she doesn’t run from it. She bares it in all its beauty, hoping that readers are able to get at least a taste of home.

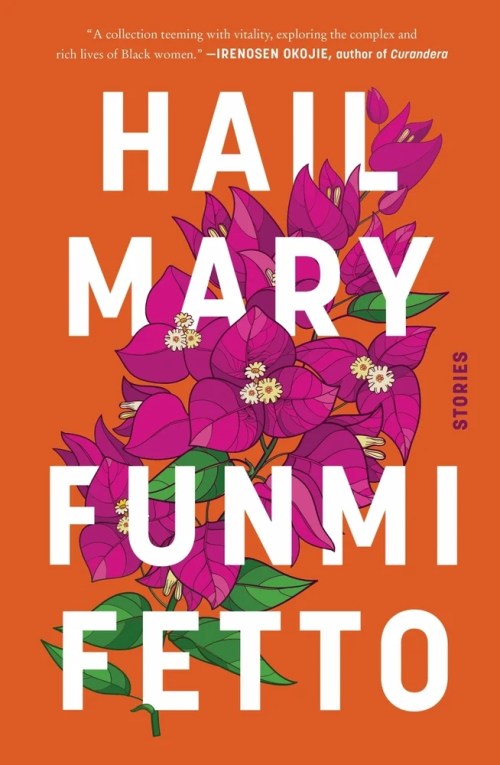

FICTION

Hail Mary

By Funmi Fetto

HarperCollins

Published April 8, 2025