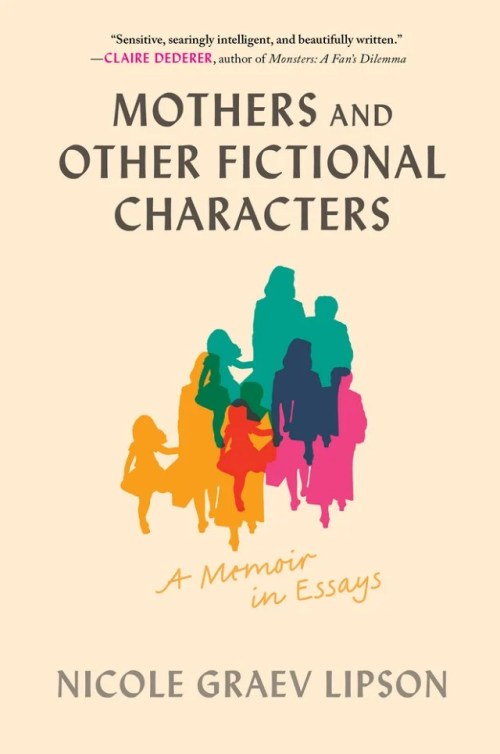

Those of us who are big readers fall in love with books either because of how they’re written or what they’re saying—I loved Nicole Graev Lipson’s debut memoir in essays, Mothers and Other Fictional Characters, for both. Let’s start with how it’s written. Oh, the writing! Graev Lipson’s prose isn’t only gorgeous, it’s skillful—dare I say masterful. Each sentence sculpted with grace, each paragraph constructed with careful planning. Each essay using a range of literary techniques, stunning in their execution.

Now for what this book is saying. So much! These essays explore the maiden, mother, and crone archetypes, focusing primarily on the mother—Graev Lipson’s own, yes, but largely, her role and experiences with motherhood. From trying to figure out what to do with her frozen embryos (an essay that, thankfully, also dives into the issue of reproductive choice) to how she handled her son’s creative yet disruptive drawing at Hebrew School, the moments depicted are mined for their larger meaning in the delightful way that makes essays worth reading. This book says a lot, but mostly, it’s about how the role of motherhood does not define a woman—certainly not “a thinker who mothers” (a much more apt description than the old “a mother who thinks”). Those looking for honest and thoughtful explorations of womanhood should check out Mothers and Other Fictional Characters.

I had the pleasure of chatting with Nicole Graev Lipson via Zoom to discuss her writing process, the memoir in essays genre, and aging.

Rachel León

Since your book deals so much with mothering and care, I wanted to start by asking how you are holding up?

Nicole Graev Lipson

I feel like every day, there’s a new wound inflicted on the world, and another crack in the safety that I feel. And I worry for the safety of my children—I worry for all children’s futures. I know I’m not alone in this ongoing grief and psychic toll. It’s almost too much for the brain and nervous system to process—the assaults are coming from so many directions, and decisions that are being made in the halls of power can feel out of the locus of my control.

With these feelings of powerlessness, I’ve been finding comfort in turning toward what’s in front of me and asking, What can I do to have a positive effect on what’s right here? I have a choice in how I interact with my children, or with the checkout person at the grocery store. Trying to act from a place of compassion as I go through my day helps ground me. It reminds me, in some ways, of the early months of having a new baby—yes, there’s much that’s very challenging about that period, but for me there was also something really clarifying. The urgency gave me an immediate sense of purpose. And I feel the same way right now. Caring for my people helps to ease some of my terror and anxiety.

This is also what I try to do in my essays: to use close observation of the daily as a way to tap into deeper truths and, hopefully, make a small difference in the world. My book is not a protest sign or a piece of legislation, but in its own way, it’s fighting for the complexity and dignity of all humans, and of women in particular.

Rachel León

“A Place, or a State of Affairs” beautifully evokes what I was hinting at in my first question: the importance of care–including self-care, which can take the form of solitude for those of us who both parent and make art. While the topic itself is worth discussing, I’d rather focus on craft here. This is such a richly braided essay with the examples of writers who needed solitude along with personal anecdotes, making it so effective. How’d you settle on the form?

Nicole Graev Lipson

Thank you. I laughed when you mentioned settling on a form because I wish that I ever “settled.” I wish I had the capacity to choose the vessel and then just fill it in. But the truth is every time I start a new essay, I’m like, “How does writing one of these work?” and I have to figure out what shape it’s going to take as I go. I have some points and memories and reflections I know I want to get to, but no roadmap. It’s a little like a friend giving you directions to their house by saying, “You’re going to pass a big fir tree and a large rock and a pancake house,” but no particulars as to how these things connect. I have pieces that I know are in there, but I don’t yet know what the connective tissue is.

For me, reading has never felt separate from living. I include so much literature in the book because there’s so much literature in my days. There’s a very thin, porous veil between the reading me and the being me. The writing of that particular essay started with a longing to understand: What exactly is solitude? And why do I crave it so bodily and deeply? And why is it that I, and other mothers I know, feel like claiming solitude is a sort of transgression? There are some culturally sanctioned ways for mothers to experience time away from the family—like, it’s okay to go out with other moms for a “mom’s night out.” That’s understandable. But is it understandable to leave your family for a night to go to the movies alone? Or to take a solitary walk under the stars? Where’s the line in terms of what’s acceptable, and why?

I entered into these questions through personal narrative because that’s always the portal for me—trying to capture what I’ve experienced in my life and body. But I also wanted to revisit some of the canonical works of American literature to consider the romantic vision of solitude that permeates our mythology, and to explore, in contrast, how solitude takes on a different, taboo form for mothers. Revisiting works like [Henry David Thoreau’s] Walden and Kate Chopin’s The Awakening and A Room of One’s Own [by Virginia Woolf] informed the writing. And then I became so curious to learn more about solitude as a psychological state that I discovered new books and thinkers I hadn’t encountered before, like the psychologist Ester Schaler Buchholz, and Philip Koch, a philosopher who’s written a lot about solitude. This new reading would inform my thinking, and that would inform my writing. And so, in ways, the form of that essay mimicked my real-life process of thinking through its questions.

Rachel León

I’d love to hear more about your writing process. There is such an assured and almost effortless grace to all these essays, so I’m curious how long does it typically take you to write an essay and what your process is like?

Nicole Graev Lipson

It’s hard to quantify how long one takes, but definitely more towards the months spectrum than weeks. Once I have a spark of an idea—something that perplexes and calls to me—I start a document. The dance choreographer Twyla Tharp wrote a book a few years ago called The Creative Habit, which is great, and I highly recommend it. She describes how any time she’s starting a new piece of choreography, she gives it a box—literally, a cardboard box. Then, every single thing that inspires or informs this dance goes into the box. This can be newspaper clippings, a scrap of fabric…anything she encounters that feels connected to what she’s creating. I don’t have a box, but I have a Microsoft Word document that functions similarly. Everything related that I encounter goes into the document, which is an unholy mess. It’s full of everything from links to podcasts, to quotes from poems, to half-sentences I think of in the middle of the night.

What’s so interesting to me about this process is that once I start the document, I start noticing things differently because the document forms a new lens through which I encounter the world. So, things that I might never have connected with solitude, suddenly feel very connected to solitude because I’m going through my days with the document in mind.

Then the work, again, is trying to figure out how to get from the rock to the pancake house to the fir tree. I also sometimes think of this as forming a constellation with words. All these different elements in the document are like stars, but I don’t yet know what picture they’re making, or where the lines between them go.

Rachel León

I’m curious how you save the documents—as the topic: “Solitude”? Or “New Essay”?

Nicole Graev Lipson

This doesn’t happen often, and it’s so incredible when it does, but sometimes I have a title from the beginning. “As They Like It” was one—this title just came to me, and I knew it would be that essay’s title. But otherwise, yes, it’s typically something like “Solitude Essay,” “Aging Essay,” “Friendship Essay.”

Rachel León

I definitely want to talk about that aging essay, but first: What was the process of putting together this book? It has a beautiful flow. Each essay building to the next, so much that it feels like they were written in this order. I’m wondering if they were and what was the process of putting this collection together?

Nicole Graev Lipson

The essays are roughly chronological. My kids are very young in the opening essays, and older at the end of the book, and that does reflect the real-life passage of time in the book’s writing. When I began the book, I was crafting individual essays intended to be standalone pieces. After maybe three or four, I started to realize they all circled around the same theme, which is the way that fiction infiltrates our lives as women. I was writing these essays in the earlier years of motherhood, when I felt that I had lost myself to certain scripted ways of being, and the writing was my way of trying to sift the truth from the fiction in my life. The writing felt like knots on a rope leading me back to myself. When I began to see the connective thread between these pieces, that’s when I realized there might be a book project here. I began to think in terms of a larger scope, and that did inform what I decided to write—what angles haven’t I really touched on yet?

I really wanted to write essays that addressed not just mothers as an archetype, but how the templates of motherhood we’re handed are just one in a continuum of scripts that we’re handed as women, from girlhood up through older age. That adds another chronological element to the book. The earlier essays focus more on earlier experiences from my life, and then the book moves through new motherhood to more seasoned motherhood, and then to being a woman in the early years of middle age, looking ahead to the rest of her life. I wanted to mimic the movement through these archetypes that we as women embody as we move through life.

Rachel León

I love the title. Its significance didn’t truly sink in until you were talking about the scripts and the fictional characters from literature you draw from. How’d you come up with it?

Nicole Graev Lipson

I did want the title to operate on multiple levels—so “fictional characters,” meaning the ways in which we can find ourselves performing stock stories of womanhood. But I also wanted to get at the ways that, in its insistence on nuance and complexity, literature can be a pathway out of these templates. I explore a lot of fictional women in my book—whether it’s Shakespeare’s Rosalind or Edna Pontellier from Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, or even Grendel’s mother [from Beowulf]—and part of why I do this is because I’m fascinated by the ways in which, because we get a window into their consciousness, imagined women can sometimes feel more real than real ones. So, I’m playing with the porous boundary between truth and fiction in numerous ways.

Rachel León

Earlier I called the book a collection, but it’s actually a memoir in essays. Was that distinction important to you—for it to be a memoir in essays rather than a memoir or an essay collection?

Nicole Graev Lipson

It doesn’t feel like an essay collection to me, and it doesn’t feel like a straight memoir. I wanted each chapter to be able to live on its own as a complete and satisfying journey for the reader. But there’s also a clear dramatic arc to the book as a whole—though it’s not an arc that follows the classic hero’s journey or Freytag’s Pyramid. Being human has never felt like a linear experience to me, but more like a series of forays or episodes that build on one another and reverberate in surprising ways, and it’s only in looking back that we can see the thematic thread that weaves itself through them. These patterns and meanings only become visible over time.

This structure also felt appropriate for a book that’s very much about dailiness. There is a lot of drama and intrigue in my book, but it’s not the sort of drama that builds to one big, revelatory moment. The movement feels more like a spiral staircase: I have an experience, learn from it, ascend a little, and then circle back. All through life, we learn important lessons, and we forget them, and we live more, and return to them, but with a different perspective. We loop backward and we grow. I hope that the reading experience feels a little bit like this–circular, but with a forward moving momentum.

Rachel León

I love all these essays, so I wish we could discuss them all! But the other I want to discuss is “Shake Zone,” if only because it’s the one I felt the most deeply. You explore the archetypes of maiden, mother, and crone throughout the book, but bring them together here in a really compelling way. Can we wrap up by talking about the crone and aging?

Nicole Graev Lipson

What I’m curious about in the book isn’t simply the stories our culture tells about womanhood, but how we absorb these stories and become complicit in their telling. I’m interested in the ways we can be divided against ourselves. There’s no place in our culture where that’s more acute than in the realm of physical appearance, beauty, and aging. As women, we can know intellectually that we should be able to age gracefully—to show our wrinkles, which are a testament to the time we’ve spent on Earth and the wisdom we have. But we also can’t help but absorb and be part of the culture in which we operate. I want to embrace my age, yes, but I also want to check myself out in the mirror, turning around to make sure my ass still looks perky.

I write in that essay about my sudden craving to be a “hot mom” as I’m facing down the end of my attractiveness—at least in terms of how our culture defines attractiveness. I wanted to explore: Is it possible to undo that learning? Is it possible to get beyond those longings? What I discovered in the writing is how much I’ve been taught, as a woman, to confuse desirability with desire—and the extent to which being perceived as a potentially sexual being informs my belief that I am a sensual, sexual being. Part of the writing of that essay, and my ongoing work as a woman, is to try to disentangle desirability from desire—to try to separate how much I might be desired by other people from my own vitality and yearnings.

What’s wild is that all of the people I’ve most respected in my life—the people who have impacted me most profoundly–have been older women: my high school English teacher Mrs. Rinden; my college writing professor, Lydia Fakundiny; women in my community, like my rabbi, with whom I have a close personal relationship. These women mentors are some of the most important people in my life, people who have shaped my understanding of who I am and of the world. The truth is that beneath my longing to be a “hot mom,” they are the models of what I most long to be. The struggle is brushing away the voices telling us we need to cling with white knuckles to youth, and stepping into truer ways of being as a woman who is getting older.

NONFICTION

Mothers and Other Fictional Characters

By Nicole Graev Lipson

Chronicle Prism

Published March 4, 2025

Rachel León is a writer, editor, and social worker. She serves as Managing Director for Chicago Review of Books and Fiction Director for Arcturus. Her work has appeared in The Rumpus, LA Review of Books, Catapult, and elsewhere. She is the editor of THE ROCKFORD ANTHOLOGY, forthcoming from Belt Publishing, and the author of the debut novel, HOW WE SEE THE GRAY, forthcoming from Curbstone.