Vi, the half-Taiwanese narrator of Maggie Su’s Blob, is heartbroken after a breakup, uninspired by her hotel attendant job in the Midwestern town where she grew up, and unable to tell her loving parents that she dropped out of college. When she adopts a sentient blob whom she can shape into her ideal white man, it seems her problems might be solved: Bob the Blob—a George Clooney/Brad Pitt/Leo DiCaprio combo, without their human baggage—motivates Vi to take care of him, wins validation from people around her, and provides unconditional companionship. Maybe they could live out their days watching reality TV in Vi’s basement apartment, where she doesn’t have to deal with her family, childhood, or ex-boyfriend. As Bob develops sentience, however, he forces Vi to confront the messiness of human relationships and the limits of the stories she tells herself.

Blob caught my eye as a novel about growing up Asian American in the Midwest—Su, who is half-Taiwanese like her protagonist, hails from Champaign, Illinois, just two hours from my hometown—and moved me with its heartful, tender insights into family, friendships, and all the roles we perform just to get through the days.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Su over video chat. Our (very rich and joyful) conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

E.Y. Zhao

What was the origin of the blob?

Maggie Su

I was thinking about relationships and how mysterious they were. The impossibility of finding someone you connect with, and even understanding how to speak to people. And the idea of a blob that you could shape, and thus understand, was interesting to me. It started off as a 10-page short story and then I turned it into a 10-minute play.

E.Y. Zhao

What were the biggest changes and challenges moving from shorter forms to a novel?

Maggie Su

The conceit stayed similar: there was always Rachel, the frenemy, and the plot points between them and Bob the Blob. But it was more of a thought experiment. And then I was like, oh no, I have to risk something and care—not that in stories you can’t care, but in novels I feel like you’re forced to. I had a professor who said in novels, you can befriend a character; in short stories, almost never. I wrote a lot of flash fiction before, I wrote poetry in my MFA, I was interested in condensation and compression. But I allowed myself to grow with these characters and let them develop, and that was the biggest difference between the forms.

E.Y. Zhao

I love the idea of befriending your characters. It also resonates with the book, which is about all different kinds of relationships. What does it mean to be in relationship with someone?

Maggie Su

Something I realized through writing this book, and through Vi, is her desire to fully understand someone. She’s so afraid of people leaving her. She wants to understand all the motivations that go into a partner so that she’ll understand when someone is going to leave. And that fear and confronting herself, not the other person, is what the book is about. And embracing the unknowability of people and connections.

E.Y. Zhao

We’re bombarded with dating shows and stories about love. What place do you feel like romantic love has in our culture right now?

Maggie Su

Vi, from such a young age, is stealing her mom’s romance novels. She’s obsessed with the horrible reality show The Swan, where they do plastic surgery, and the idea of transformations and secret identities. It’s hard, when you buy into those narratives, to have romantic relationships that don’t disintegrate because of unspoken, unseen societal expectations. I think so often in romantic relationships, there’s so many scripts happening. So many heteronormative, white romantic things we don’t realize we’re buying into, like “love at first sight,” “half of the whole,” those kinds of things. Part of this book was grappling with that and how it leads to a self-worth issue for Vi. There are people she’s trying to be with and people she’s trying to perform as, and when that falls apart, her sense of self falls off. She’s not able to understand who she is beyond the relationships. And it’s corny, but Vi has to figure out who she is beyond what she’s been told and her own fears of being left and being alone.

E.Y. Zhao

Vi is adamant that she doesn’t have an originary trauma story, though she remembers a lot of messed up things, like racism, bullying, and neglectful things her ex does. Overtly, she says, “I don’t have an excuse to be dysfunctional. My childhood was normal. My parents are loving.” How did you think about the relationship between past and present and how we narrativize it?

Maggie Su

Especially in Asian American novels, novels about race and identity—trauma narratives as well—it’s tempting to draw straight lines. So I wanted her to be explicit: this isn’t the thing. There’s many things, right? I wanted to think about the ways in which she has both been shaped by her environment and the ways in which she’s been an actor. So like that flashback where she’s horrible to her childhood friend, there’s so much going into that: jealousy of her whiteness, class. And we’re seeing so much more of this in popular culture, but the messy Asian American woman—that is what I love, that’s what I wanted to see more of. I didn’t feel like Asian American narratives that I’ve read, until recently, were embracing that mess, the sexuality, the grossness. I wanted to think about, like, masturbation, and these formative moments that aren’t talked about, especially for women of color.

E.Y. Zhao

What books do you recommend about messy Asian American womanhood and personhood?

Maggie Su

The short story collection Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang. Her writing style is so full and visceral, and very different than mine, and I loved how it played with the immigration story. Joy Ride I watched on a plane—I was like, I don’t think the people behind me should be seeing this. It’s wonderful. I love Ling Ma’s Severance. I’m inspired by how many writers of color are using speculative conceits. I loved Parasite, and Past Lives was excellent; I’m just naming Asian American things now, but I am so excited to see these different representations. And inspired to think about how to twist the immigration narrative, the master scripts—which have been done beautifully, but I feel we’re ready for different types of Asian American stories.

E.Y. Zhao

Vi’s mom is white and her dad is Taiwanese. They navigate her mixed upbringing with such love and good intention, but despite that, they can’t insulate her from the racial politics of the place she grew up and the wider world. Blob was a sensitive, beautiful rendering of that dynamic. Was there anything in the writing process, thinking through her mixed-race heritage specifically, that struck you or you found challenging?

Maggie Su

I’m also mixed-race and grew up in the Midwest; there’s a lot of details from my life. I called it a love letter to my younger self, but also, Vi is not me. So it is really personal, and it’s been wonderful to hear people who’ve connected to it because in certain ways it feels like a niche situation. But also, it’s not. There’s tons of Asian Americans in the Midwest, it’s just that our stories aren’t as prominent as Asian Americans on the coasts. I was very aware of that and wanted to represent that feeling of otherness that felt so specific. And I talk in the book about these kinds of Midwestern parents, this Midwestern niceness, and her kind of resenting her dad’s assimilation. It means a lot to have people read and respond to it.

E.Y. Zhao

Vi works in the college town where she grew up, so her childhood is contiguous with her adult life. It’s such a specific experience. Was Blob always going to be set up that way?

Maggie Su

I think it was. The town in the novel is a conglomeration of Champaign, Illinois, and Bloomington, Indiana, where I got my MFA. I worked at a hotel as a front desk attendant one summer during my MFA and that liminal space, people coming in and out…People often forget hotels aren’t their home, so you get to see them with their guard down at breakfast, and there was always something fascinating to me about Vi as the observer.

E.Y. Zhao

But often she’s like, “This is too much, I want to disengage.” Which is different from many narrators; a lot of them are writerly, always paying attention.

Maggie Su

Definitely. And I also think it’s Bob that makes her want to engage again. She’s just playing solitaire, and then Bob comes along and she’s like, let me engage with this world that I’ve actually been in for quite some time. And look at these people and try to imagine their lives.

E.Y. Zhao

In that way, early Vi reminds me of characters in “refusal literature,” like Bartleby or the narrator of My Year of Rest and Relaxation. All she wants to do is sit in front of her TV, eat Froot Loops, and exist. A lot of us feel that way, and not like a special narrator who undergoes a ton of growth. Were you thinking about that tradition of literature?

Maggie Su

Yes. I rewatched the first episode of season 2 of Fleabag and I was thinking about these messy narrators…what makes them watchable is not that we agree with everything they do or we think they have the high ground, but that there’s something unapologetic and brazen and radical about them. Also, humor helps. Fleabag without the humor would be almost unwatchable. And so that’s what I wanted to add: I think Bob adds quite a bit of levity to Vi’s life, gives her something to grasp onto.

It’s hard. They tell you your characters have to act, your characters have to do things and go places, and Vi just wants to rot in bed. That felt very real during the pandemic. It felt very real during many parts of my life, struggling with anxiety and depression, and what brings us out isn’t necessarily some big action. Like her deciding to go back to college. That’s not small, but in terms of the novel, it’s not huge. But, yeah, like, I need to start trying again, whether that’s getting up or having my landlord wake me up.

E.Y. Zhao

What do you feel like you’ll explore next in your writing?

Maggie Su

My partner watches a lot of horror movies, so I’m interested in where horror is going and thinking about speculative elements and location. I’m thinking a lot about the Midwest, the writing that comes out of this place that feels like nowhere but also is the heartland, that contradiction. To belong, to be a local but not a local, and the townie/not-towniness of it all, which Blob got into a bit with Vi’s experience growing up in a college town. I’m living in northern Indiana now—I think it’s 1% Asian, or maybe one thousand Asians? So I’ve been reading folks who are writing specifically about being Asian American in the Midwest. My dear friend Marianne Chan, a poet, wrote Leaving Biddle City—it’s a fantastic encapsulation.

FICTION

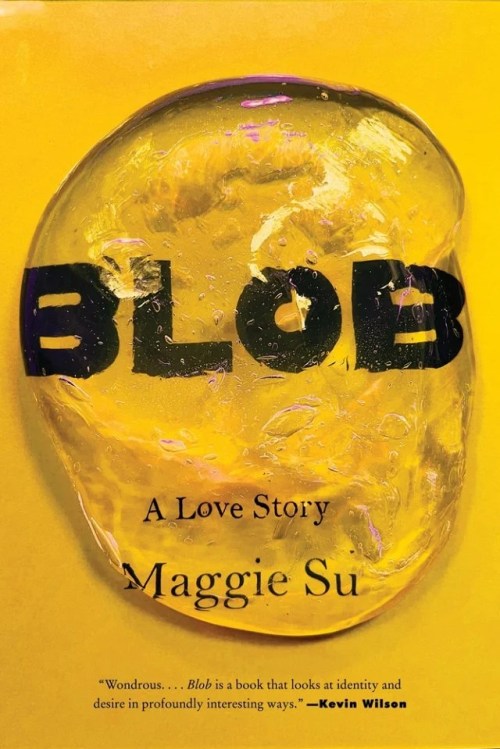

Blob

By Maggie Su

Harper

Published January 28, 2025