The following is a conversation between acclaimed novelist Hannah Lillith Assadi and Omar Khalifah, author of Sand-Catcher.

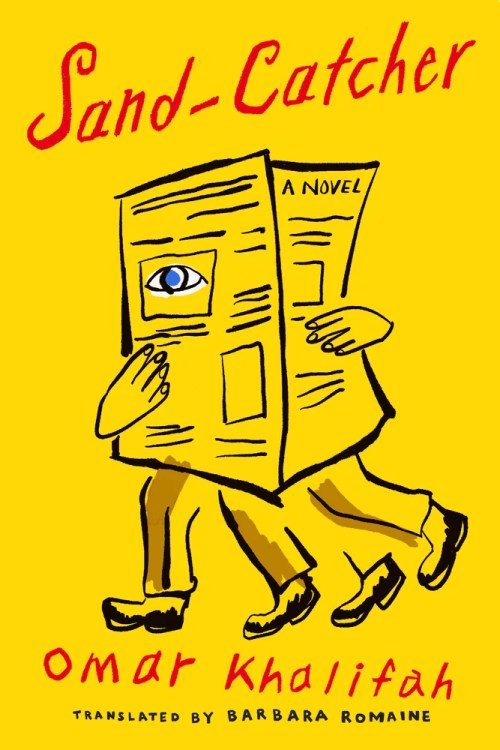

Sand-Catcher follows four young, Palestinian journalists who are tasked to profile one of the last living witnesses of the Nakba, the violent expulsion of native Palestinians from the nascent state of Israel in 1948. However, they find that their interviewee has no desire to have his memories preserved or to become an inspiration for future generations. The journalists must then decide how far they’re willing to go to balance the man’s demand for privacy and the need to record his story.

Hannah Lillith Assadi

As a long time friend, I’ve had the privilege of following both your academic and literary work for many years (almost two decades!) Most recently, I read parts of your academic manuscript, which interrogates the historical uses of Holocaust memory particularly vis-a-vis Zionism, as well as the overreliance on Nakba memory in some Palestinian literature. So too, your brilliant debut novel, Sand-Catcher, thematically echoes some of your scholarly concerns. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about switching between these two modes of examining memory.

Omar Khalifah

My interest in the location of the Nakba in Palestinian literature dates back more than two decades. When I was an undergraduate student in Jordan, I remember having conversations with friends about the assumed absence of Nakba novels. Why haven’t Palestinians produced so many narratives about the Nakba? Palestinian literature has been identified more with a poet (Mahmoud Darwish) than with a fiction writer. Is Palestine more suitable for poetic imaginations? Has the exile of numerous Palestinian writers stripped them of the ability to narrate a land that some of them haven’t even seen?

These early questions have matured over time. I cannot quite remember the moment I was introduced to memory studies, but I’ve found myself immersed in research about remembering the past. As I was reading the literature, I found myself interrogating the premise of some common arguments about the location of the Nakba in Palestinian literature. For example, the assumption that remembering the Nakba has always been a driving force of Palestinian literature, or that Palestinians need to remember the Nakba in the same ways Jews have remembered the Holocaust or Armenians have remembered their genocide. That the Nakba must be finally admitted into the world of remembered calamities. But what if the Nakba has certain particularities that complicates any attempts at turning it into a memory? And what if some Palestinians view remembering with suspicion or as a less useful tool in their anticolonial struggle? As I was toying with these thoughts for an academic book, I became obsessed with an idea for a narrative plot that precisely revolves around the refusal to remembering the Nakba. At the time, I was also trying to free myself of academic concerns in order to go back to creative writing—which I do in Arabic. My first short story collection was published in 2010, and I was still waiting for my first novel. I wanted to announce myself differently among fellow Palestinian writers, so I wrote Sand-Catcher.

Hannah Lillith Assadi

One of the things you’re dismantling in Sand-Catcher is the illusion of a singular Palestinian experience, and even some monolithic idea of what being Palestinian means. You and I spent so many nights while we were at Columbia discussing around this, and it remains a source of some distress to me especially in this moment of genocide as a person who is both Jewish and Palestinian. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how this tension manifests in the book.

Omar Khalifah

I don’t want to sound too post-modernist here. There are definitely certain essences that define the Palestinian experience. The Nakba is one of them. But I wanted to defy some common expectations about how injured people should deal with their catastrophe. And the Nakba is ongoing—it is not simply past, which adds more to the complication of our experiences.

People tend to like simple designations. For many, Palestinians are heroes, or victims, or revolutionaries—and we ourselves like sometimes to project this. But Palestinians are much more than that, and in our inner circles, we occasionally joke about our experiences. Is there a space for sarcasm, mockery, and irony in Palestinian literary articulations of their experiences, including the Nakba? This is another source of inspiration I had when I was writing the novel.

There are few sarcastic Palestinian writers—and understandably so. I fully understand that people may be offended by unconventional telling of their tragedies, especially at moments of crises like the one we currently experience. But I also believe in the role of literature in imagining different realities. As a Palestinian writer, I don’t want to be turned into a familiar textbook, nor to feel coerced into an echo-chamber.

Increasingly, new voices in Palestinian literature have produced surreal, absurdist, and sarcastic images of Palestine. And I think the Palestinian condition is conducive to this. Palestine is an anomaly—a people in the supposedly postcolonial world order who nonetheless still live under colonialism. We moved from British colonialism to Zionist colonialism—and stopped there. Time doesn’t move. It is suffocating.

Hannah Lillith Assadi

Perhaps as a follow up, how did you conceive of these particular characters? Which of the four journalists came first? Or was it the elderly man?

Omar Khalifah

I only had one image when I began writing the novel: an elderly survivor of the 1948 Nakba who refuses to share his memories with others. I didn’t do much planning before starting the novel, but once I started, I kept a journal where I wrote possible scenarios for developing the story.

Hannah Lillith Assadi

That’s interesting. So, in a way all of these characters grew out of him…To change course a bit, we’ve chatted a bit over the past 14 months about the impossibility of writing while bearing witness to the genocide, a sort of no poetry after Auschwitz moment, except here, it is no poetry after Gaza. Much of the positive response to your novel (and I agree with all the raves) is in your book’s refusal to accommodate the Western appetite for the “trauma plot.” And yet at the same time, we are all ingesting real time trauma, as we watch image after image come out of Gaza. Could you talk a bit about how you’re navigating this, this looking from across the distance of a phone? And at the same time, why it was important to refuse it in the novel?

Omar Khalifah

Much to unpack here. Let me, first of all, respond to the Auschwitz reference. I hope what I am about to say won’t be misunderstood, but I don’t like to draw on Jewish experiences during the Holocaust when discussing Palestine/Israel. This is because references to the Holocaust have largely served to exceptionalize and homogenize Jewish experiences, something that Zionism has long weaponized for its own political ends. As a Palestinian, I don’t like to use the “Jewish metaphor,” if you will, because that metaphor may mask the nature of Jewish colonialism in Palestine.

But the gist of your question stands: what does it mean to write after Gaza? I think it simultaneously means everything and nothing. It is absolutely normal to take a break from writing, to feel that writing should be de-prioritized at this moment. And we need to be humble about our expectations: we don’t write to “give voice” to Gazans, or to “register” that which otherwise will be forgotten. Gazans have been continuously bombed to death, in real time as you mentioned, and nobody cared.

It is still early to expect how Palestinian literature will develop after Gaza, but I am pretty sure there will be huge changes. But one thing I hope won’t happen: to turn Gaza into another trauma story. One of the issues I have with the “trauma plot” is its implied universality: that all catastrophes and disasters can be subsumed under the category of “trauma.” I don’t think the Nakba is trauma. Trauma connotes a distant event in the past and a deviation from the normal. But the Nakba is a normalization of violence against Palestinians. This isn’t trauma. This is Nakba.

Hannah Lillith Assadi

In terms of the overuse and weaponization of the “Jewish metaphor” to Palestine, I’m thinking of how much that’s been internalized as well. I always think of this interview in Jean Luc Godard’s film Notre Musique, where Mahmoud Darwish says to an Israeli journalist that the only reason the world cares about Palestinians is because “you are our enemy.”

And yes, it feels almost impossible to write in these days, but I am still curious if there is a new fiction project brewing?

Omar Khalifah

This brings us back to your previous question. There are certain competing ideas in my mind, but I don’t think I will be able to put them on paper now. And it is hard for me to think simultaneously about fictive and scholarly writings, especially that I write each in a different language. One thing for sure though: I miss writing in Arabic—I even need it. It is soothing to write in it, even if the subject of my writing is distressing and depressing.

Hannah Lillith Assadi

Yes, I remember you saying you could only write passionately in Arabic. It’s always made me sad that I don’t have access to it like that. On another note, in terms of language and influence, it’s been a long time since you and I had a late night talking about books and literature, but I vaguely remember your fondness for Borges. What other literary or artistic inspirations were a part of this novel’s DNA?

Omar Khalifah

I will leave it to readers to detect if there is something Borgesian in this novel. But I think I was also in conversation with other Palestinian and Arab writers who wrote about the Nakba. Once character in the novel even referred explicitly to Elias Khoury’s important novel Gate of the Sun. Satirical styles of some Arab novelists are also an influence, such Egypt’s Sonallah Ibrahim, Lebanon’s Rachid Daif, and Palestine’s Emile Habibi.

Hannah Lillith Assadi

The grandpa keeps repeating, “Palestine was lost” and later, in the final pages of the novel, this line is repeated to devastating effect.

Does anything give you hope of return?

Omar Khalifah

The short answer is “no,” but let me elaborate. One of the astonishing things about Palestinians is that against all odds, the overwhelming majority of us still think we will triumph. I am not sure about the exact source of this belief. Perhaps it is our messianic belief that good will win over evil or that there must be a light at the end of the tunnel. This is astonishing not only because it is in stark contrast to the power differential on the ground, but also because in most cases of settler-colonialism (what Zionism is), indigenous people have, unfortunately, irrevocably lost.

Palestinians need to reckon with the fact that pre-1948 Palestine has been irrevocably gone. So even if Palestinians returned, they would return to a different Palestine. This is perhaps what Mahmoud Darwish meant when he said on his first visit to Palestine after the Oslo Accords of 1993: “I went back, but I didn’t return.” In more than half of historic Palestine, the geography itself no longer exists, as Israeli colonialism has managed to obliterate entire villages and landmarks since 1948. And look at Gaza now. It is gone. These things don’t “return.”

Perhaps we should rethink the meaning of return, liberation, and triumph. Our liberation should rest on defeating Zionism, winning the intellectual battle, and erasing racist Zionist ideology from Palestine. Palestinians should always insist that Israeli colonialism is one of the biggest robberies of land and history in modern time. The question is how to translate that Palestinian belief into political reality on the ground. I used to say that I believe in a one-state solution, but after what I saw in Gaza, I nearly lost hope of ever imagining a future of co-existence with Israeli Jews. Much needs to be done. Much needs to be repented for. And there is no sign that any of this will ever happen.

FICTION

Sand-Catcher

By Omar Khalifah

Translated by Barbara Romaine

Coffee House Press

Published December 03, 2024

Hannah Lillith Assadi is the author of Sonora (Soho 2017), which received the Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and was a finalist for the PEN/ Robert W. Bingham Prize. Her second novel The Stars Are Not Yet Bells (Riverhead 2022) was named a New Yorker and NPR best book of 2022. Her third novel Paradiso 17, inspired by the life of her late Palestinian father, is forthcoming from Knopf in 2026. She teaches fiction at the Columbia University School of the Arts and the Pratt Institute. In 2018, she was named a '5 under 35' honoree by the National Book Foundation.